by Glenn Dreyer

In early 2007 I purchased a border pipe from Dr. Louise Mark of County Cork, Ireland. The set had a bass and two tenor drones, and upon receiving them, I realized they were significantly larger than the border pipes I was most familiar with, a 2005 set made by Richard and Anita Evans. It turned out that they were a reproduction of an antique bagpipe.

The seller informed me that these pipes had been made by Brian McCandless in 2000. Brian will be known to some pipers as one of the people who started the North American Association of Lowland and Border Pipers (NAALBP) back in 1989, along with Alan Jones and Mike MacNintch. Brian also edited the Association’s journal during its seven issue run from 1990 through 1994. A multi-talented musician, musicologist and scientist, Brian also knows his way around a lathe.

back in 1989, along with Alan Jones and Mike MacNintch. Brian also edited the Association’s journal during its seven issue run from 1990 through 1994. A multi-talented musician, musicologist and scientist, Brian also knows his way around a lathe.

A few years ago I managed to obtain copies of the NAALBP journal, and was pleased to find an article about the bagpipe that my reproduction set was based on. Here is a portion of “Pipe Dream Come True” (NAALBP Journal No. 2, 1991) by Mike MacNintch, which describes how Tom Childs of Massachusetts obtained the original:

Tom had been playing at a Scottish function when an older gentleman approached him and asked if he knew anyone who wanted to buy pipes. The man said that he had a couple of Highland sets, some Irish pipes, and some Northumbrian pipes. Tom was intrigued but played down his interest and casually took the man’s number. Later he recalled “I counted the days, hours, and minutes until I was able to call this man”.

Upon visiting the man, who happened to be an antique dealer, Tom was forced to hear an hour long speech concerning the restoration of antique clocks. The whole time the various pipes were in full sight, and Tom could plainly see that there was a set of Border pipes on the table. “My eyes were bulging clean out of my head”, says Tom. The pipes were ivory mounted blackwood! The bag was shot and there was no chanter, but the rest of the instrument was in fantastic shape. At first Tom did not expect to be able to afford them, but it turned out that the man only wanted hat he had paid for them back in the fifties.

About three weeks later, Tom returned and paid for a regular treasure trove -the Border pipes, two Uilleann pipe chanters (one a double chanter with keys), and a bellows. There was also a “thing” that appeared to be a drone-end which was converted into a chanter, quite unsuccessfully.

At the 1990 Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention Tom showed the pipes to both Gordon Mooney and to Sam Grier. Both agreed that the pipes were from the period between 1760 and 1820, the Regency period, and that they were a typical Border set.

Tom soon enlisted the expert services of Mike MacHarg for a new bag and chanter. The rather nice piece of yellowed ivory at the end of the “thing” became the sole for the new chanter – it matches the drone mounts very well. The bellows have yet to be restored, but the pipes are going well and play near A.

I am not aware of that anyone has been able to indentify the maker or narrowed down the production date. Brian McCandless later acquired the pipes from Tom Childs, and decided to reproduce them. The copy he created for Louise was made of African blackwood and artificial ivory. In Brian’s words from a 2007 e-mail to me:

Photo of the antique drones from Brian McCandless' website.

The drones I made for Louise are a replica of the set of drones and stock that Tom found in Boston in the 1980’s. I made the chanter after a prototype I developed to go with the original set (I have made 3 chanters to this specification). The original set of drones are reeded with a composite reed for the bass drone (brass tongue) and cane reeds for the tenor drones. In comparing the original set with other 19th and 18th century sets, it seems that the drone bores are wider, giving a sound that tends towards Highland pipes, and I have wondered if the set was made by a Highland pipe maker.

Louise Mark and her husband were in the US doing post-doctoral work at Cornell University. Louise’s husband is a uilleann piper, and they attended the Piper’s Gathering at North Hero, VT, where she fell in love with the sound of the border pipes. She made contact with Brian and took the pipes he made her back to Ireland. By 2007, with a second child on the way, she decided to sell them rather than let them sit under the bed not being played for years.

OBSERVATIONS ON THE REPRODUCTION DRONES

Having never seen the original pipes that my reproduction set is based upon, my observations and speculations are based on the assumption that Brian produced an exact copy of the antique set.

After reviewing images of border pipes in museum collections that I have been able to locate, it is clear that there was little standardization of 18th and 19th Century instruments. Border or Lowland bellows pipes with a bass and two tenor drones seem to be more common, at least in museum collections, than the bass, tenor, alto drone configuration that is more popular today. For example, Anita Evans’ photos of border pipes from the Morpeth Museum includes 8 sets of drones with two tenors and 5 with the tenor alto combination.

The compact disk of National Museums of Scotland bagpipe data that accompanies Hugh Cheape’s “Bagpipes, A National Collection of a National Instrument” totals 8 sets with bass and two tenors, 2 sets with three different drones, and 2 undetermined (no image and minimal description).

Outer ornamentation, including ferrule treatment and the shape of drone bells, also varies greatly in the available photos of antique sets. As with the McCandless reproduction, some of the museum instruments have two beads below all three drone tops and the upper part of the bass middle joint, which function as cord guides in Great Highland Bagpipes, but are unnecessary with a common stock instrument. To me this suggests a highland pipe maker, or at least one with an inclination to use the GHB as the ornamentation model.

These pipes have one ornamentation feature that I have not seen on any other bagpipes, a small bead on the bottom of the ferrule and top of the drone caps that is raised beyond the body. Such beads are usually formed by cutting a groove near the edge so the bead is actually at the same height as the ferrule or cap body. This is certainly a design flaw, at least for pipes with artificial ivory ornaments, since these elevated beads have chipped in a number of places just from normal handling. Particularly brittle artificial ivory has not helped.

As for the size of these pipes, I was right about them being noticeably larger than an Evans set, but it seems Evans are making border pipes at the smaller end of the size range.

Tenor drone comparison, top to bottom: D. Glen GHB circa 1890; McCandless reproduction; Hamish Moore 2000; Richard and Anita Evans, 2005.

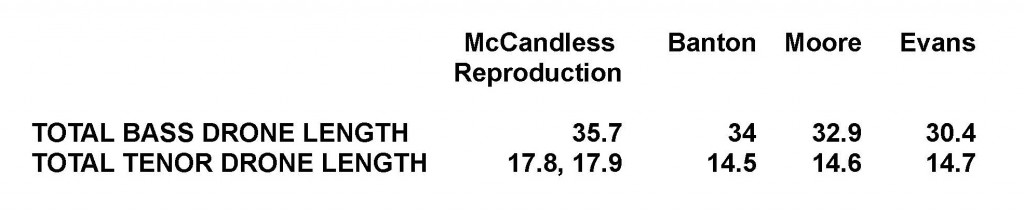

In the photo above the tenor drones are lined up to the left by their reed seats, and each have the same amount of tuning pin exposed (about 1 inch). The McCandless tenor is even longer than a classic Great Highland Bagpipe drone, and much fatter than the Moore and Evans drones. One quantitative means of comparing drones is to add up the total lengths of all the parts.

Clearly the tenor drones on the McCandless reproduction are significantly longer than the three contemporary sets. The bass drones have more variation, with Nate Banton’s approaching the McCandless set.

Regarding bore dimensions, the tenor bottoms are quite different from each other at 0.196 and 0.24 inch respectively, while the tenor tops are the same 0.37 inch diameter with 0.324 bushes. All tenor bores are larger than the Banton, Moore or Evans pipes also measured. The bass drone, while long, has a smaller bore in both the bottom (0.202) and the mid sections (0.245) than the comparison sets. The top bore (0.43) is much bigger than the Evans set, and about .03 in wider than Banton and Moore.

Reeding the pipes and trying to get them to play at concert A pitch has been challenging. They came to me with short, wood-bodied drone reeds with brass tongues. I am currently using that wooden one in the bass and two of Nate Banton’s synthetic drone reeds in the tenors. While setting the latter reeds up, Nate reduced the larger tenor bore with “rushes,” (lengths of metal wire in this case). Nate had the same problem that I did of getting the set to play up to A, and speculated that it might have originally been a G set. It certainly seems to want to play a bit flat of concert A, though with Nate’s help, A is now possible. The sound is rather tenor heavy, not surprising given two tenors with large bores. I’m still looking for a reed that will give the bass drone a bit more depth and volume, probably cane.

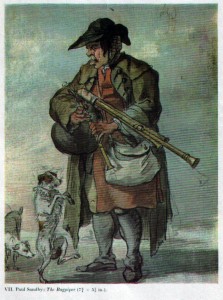

Was the original a Highland bellows pipe? As documented in the current issue of Common Stock (volume 28, no.1, June 2011) bellows blown pipes with tapered chanter bores where common in the Highlands, Lowlands and in pipe maker’s catalogs throughout the 19th century. Paul Sanby’s sketch of a piper, presumably done while he worked in the Highlands, indicates these pipes were being played in the 18th century as well. The pipes in Sanby’s watercolor are quite large, likely pitching in D (they seem about the size of John Swayne’s D border pipes). One thing seems certain, “Border” or “Lowland” as the name of these pipes implies a narrow geographic range which seems less accurate as we learn more about where they were actually used.

Acknowledgements. Thanks to Nate Banton for supplying measurements of the McCandless pipes as well as his own, and for reeding the pipe. Steve Bliven loaned me the NAALBP Journal to scan. The Sanby watercolor is from Aron Garceau’s fabulous Bagpipe Iconography website.