To download the original scanned Journal as a pdf please click here.

————————-

————————-

ANTIQUE SCOTTISH SMALLPIPES BELONGING TO ALAN JONES

ANTIQUE SCOTTISH SMALLPIPES BELONGING TO ALAN JONES

————————

JOURNAL

OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 1 JULY 1990

CONTENTS PAGE

QUOTATION PAGE………………………………… 2

FROM THE CHAIRPERSON by Alan Jones ………………. 3

DESCRIPTION AND

NOMENCLATURE OF LOWLAND

AND BORDER PIPES by Brian McCandless …………………. 5

RECOLLECTIONS OF SCOTS

SMALLPIPES by Sam Grier ………………… 12

BAGPIPE COLLECTION AT THE

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART by Mike MacNintch ………………. 18

ESSAY – WHICH CAME FIRST…

THE PASTORAL-UILLEAN PIPE

PROBLEM by Brian McCandless ………………… 20

REVIEWS:

– NORTHUMBRIAN PIPING CONVENTION

AT NORTH HERO, VERMONT 1989 …………….. 27

– HAMISH MOORE SMALLPIPE WORKSHOP 1989 …………….. 29

– EVENING OF BAGPIPES ………………….. 29

– LOWLAND PIPES AT BALTIMORE FOLK MUSIC FESTIVAL ……………….. 29

– MUSIC REVIEW: GORDON MOONEY – O’ER THE BORDER ……………… 30

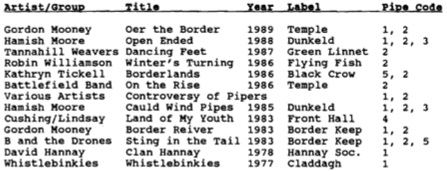

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY ………………… 31

TUNES: …………………….. 32

– A BORDER BALLAD and GALLOWA’ HILLS ………………. 33

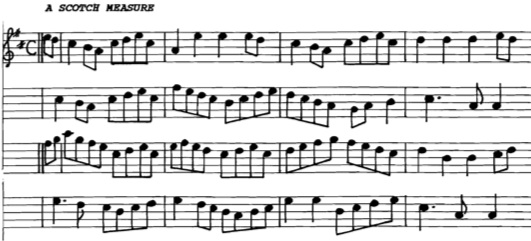

– A SCOTCH MEASURE and CHARK’S HORNPIPE…………………… 34

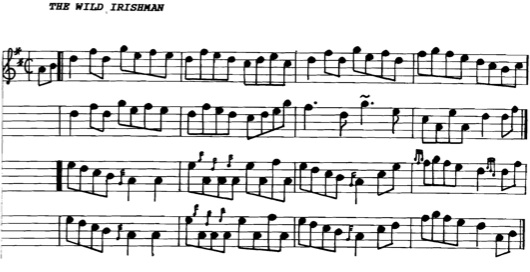

– THE WILD IRISHMAN and IOMRAMH EADAR IL’A’UIST ………………. 35

– MEILLIONEN and PIBDDAWNS GWYR GWRECSAM …………… 36

NOTES ON TUNE EXECUTION……………….. 37

SHORT NOTES …………….. 38

BAGPIPE MAKERS AND PIPING SUPPLIERS ……………. 39

REFERENCES ………………… 40

MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION ………………. 41

—————————

QUOTATION PAGE

A PIPER

A PIPER in the street today,

Set up, and tuned, and started to play,

And away, away, away on the tide

Of his music we started; on every side

Doors and windows were opened wide,

And men left down their work and came,

And women with petticoats coloured like flame,

and little bare feet that were blue wit cold,

Went dancing back to the age of gold,

And all the worked went gay, went gay,

For half an hour in the street today.

by Seumas O’Sullivan (1879-1958), from Verses:

Sacred and Profane, 1908.

EXCERPT

...And I gives this wee kind of shrug, up there on top of the door, and when I do that the pipes slip out from under my jersey and fallon the stone landing. Something breaks. From up there I can't see what. The Professor's just arriving. He hears his pipes fall and break, but I don't think he sees them fall. I don't want to see him anyway. I just turns my face to the wall. He doesn't say a thing. Just picks up his bagpipes, and off down the stair and out the close. He never came back. Not as far as we know, anyway. He'd no business to have moved in, when you think about it. It wasn't as if he needed to live up our way. I don't think he was all that right in the head. From "You Don't Come the Pickle with the Onion" by Peter Chaloner, 1984

VERSE "As we went oot ayont the buck, It's she came in aboot the Balloch, Roy's piper he was playin' 'She's Welcome Hame tae Aldivalloch'."

From “Roy’s Wife”, an old Scots song about Isobel Stewart, wife of John Roy of Aldivalloch, who ran away with David Gordon of Kirktown in c.1730. After being chased over the Braes of Balloch by old Roy, she was safely returned home.

2

FROM THE CHAIRPERSON by Alan Jones

Within the last decade or so, there has been something of a renaissance of interest in Lowland and Border bagpipes, culminating in the formation of a Society of Lowland and Border pipers in Scotland, the emergence of some really fine players, the issuing of a number of excellent recordings, and the production of both a tutor book and some historically researched and well documented tune books. Not to mention the much greater availability of newer instruments now emerging form the workshops of numerous professional pipe makers.

For these reasons alone, I believe that today, the Lowland and Border bagpipes are heard by a wider audience than ever before.

I have great deal of enthusiasm for Lowland pipes and piping in general and strongly feel that the pooling of energies, resources and knowledge can only be of mutual benefit to all those persons with an interest in this subject matter. Hence, the raison d’etre for our newly formed association.

I have been inspired by Brian McCandless’ own genuine eagerness and enthusiasm to promote the playing and understanding of the Lowland pipes, and when he approached me to act as a chairperson to initiate getting the Association off the ground, I wonder if I was really a good candidate for such a position.

I agreed to “run”, providing there was a clause in the application form for the prospective membership to vote, viz a viz: a “Yes” or “No” to my election. Since the ensuing vote turned out to be unanimously positive, and with a little extra encouragement from Brian, I subsequently gave my full acceptance to the position.

In having a forum by which persons with a common interest can get together, draw on mutual resources, and generally benefit from the free exchange of ideas and information can only be for the good of all concerned.

It naturally follows that a society or association is only as strong as its membership, and I do hope that all those who have decided to join (for the very nominal free specified), will be active in the Association to benefit the membership and to promote Lowland piping in whatever way they can – no matter how small their contribution. As a practicing Lowland piper, I feel that Brian McCandless is an excellent candidate for Association coordinator – through his enthusiasm, practical experience and with the resources at hand to produce the newsletter. I do hope that you will all support his endeavors so that the Association can move forward in a positive manner, and subsequently go from strength to strength.

3

The provisional constitution and ideas that Brian has proposed are exciting goals for the Association to aim towards newsletters, sponsoring an event, publishing a tune book and producing a cassette, etc., etc.

In this, our first newsletter, we do hope you find its content interesting; even inspiring enough to consider putting pen to paper and making a personal contribution for newsletter #2. How about a few lines on how you became interested in Lowland/Border piping, some information on your own instruments, and a little about your piping activities to date.

With the aforementioned upsurge of interest in lowland piping and through my own genuine enthusiasm, I wholeheartedly support this newly formed Association of Lowland and Border Pipers of North America. I hope that by joining and showing your support to our initiative, we just may prove to have a very exciting future indeed!

Alan Jones, 1990

DESCRIPTION AND NOMENCLATURE OF LOWLAND AND

BORDER PIPES by Brian McCandless

Lowland and Border Pipe Typology

In this, the first issue of the Journal of the NAALBP, I would like to introduce you to the bagpipes that fall under the general classification of Lowland and Border pipes. Amidst the historical confusion and the clamour of resurgence about these instruments, offer a simple framework against which pipes may be compared and contrasted. In this discussion of bagpipe typology, I advise you to bear in mind the following:

1) a name or “type” is only a label – it has different meanings at different times to different people living in different places.

2) hybridization has been and is a common phenomenon among instrument makers, especially to those not bound to strict traditional guidelines – in some instances, innovation itself may be the tradition.

3) there is no “complete” historical discussion of bagpipes, especially in light of meager documentation, continuous cases of isolated innovation, and strong nationalistic opinions about bagpipes. Hence, let the classifications presented here serve as a guide to your own discoveries of these fascinating and beautiful instruments.

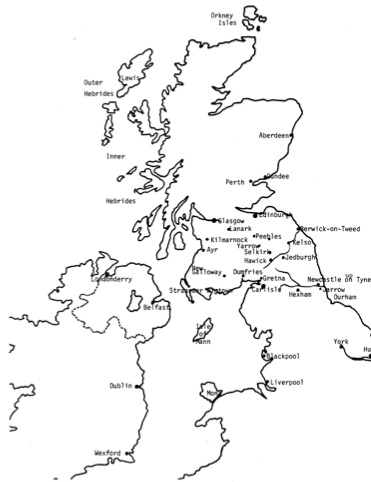

There are three features which, when taken in combination, serve as a general means of identifying Lowland and Border pipes:

1. They were/are found in the Lowland and Border region of Scotland, defined roughly as but not limited to the trapezoid bounded by (clockwise) Newcastle, Stranraer, Glasgow, and Perth (see map on inside cover) from about 1600 to the present.

2. They are inflated with a bellows. This is also known as “dry-blown”. In 18th century Scotland, pipes of this type were referred to as “cauld wind pipes”. Where the inspiration for bellows inflation originated is a matter for debate, but its consequence was that a wide range of reliable reed-chanter combinations were possible, resulting in a tonality spectrum from soft and delicate (Scottish smallpipe) to loud and strident (Border pipe).

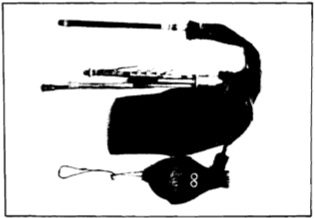

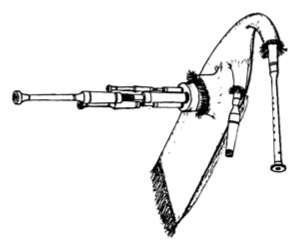

3. They typically carry a chanter for playing the melody and two or more drones in a common stock to give a sustained harmony. Some instruments carry two chanters mounted in parallel. The chanter utilizes a double bladed reed while the drones use single bladed reeds. An exception to this is the early form of Northumbrian smallpipe, which had “shuttle” drones using double bladed reeds, like the French Court Musette. Some instruments carry an extra pipe in the drone stock which has a double bladed reed and is keyed or otherwise stopped in an arrangement known as a “regulator”. The regulator is used to make chords with the chanter notes “on demand” and is a feature of the Scottish Pastoral, Union, Reel, Chamber, and Irish Uillean pipes. Below is a photograph of an antique set of Lowland pipes, showing three drones in a common stock and a conical

bore chanter.

5

Figure 1. Photograph of an antique Lowland bagpipe (from Bagpipes,

Figure 1. Photograph of an antique Lowland bagpipe (from Bagpipes,

by Baines, 1960).

______________________

For the purpose of discussion, I use the term “Lowland Pipe” to refer to the broad category of instruments that possess a bellows, open ended chanter, and simple drones (i.e., no regulator) . Pipes with regulators go by a variety of names depending on where you look and who you ask. Northumbrian pipes are fairly well characterized historically in works by Stokoe and by Cocks and Bryan (see References). Some authors (Baines, for example) identify Lowland pipes as a particular style of the instrument, but more recently, Collinson allows a broader definition of the instrument. Thus, we find Lowland Pipes, Regulator pipes, and Northumbrian smallpipes:

Lowland pipes

1. "Generic" Lowland pipe 2. Border Pipe 3. Northumbrian Half-Long Pipe 4. Scottish Smallpipe

Regulator Pipes

5. Scottish Pastoral, Union, Reel, or Chamber Pipe 6. Irish Uillean Pipe 7. Scottish Smallpipes with regulator (a modern hybrid)

Northumbrian Pipes

8. Same as number 2 9. Shuttle Pipe with open chanter 10. Smallpipes with open chanter (akin to Scottish Smallpipes) 11. Smallpipes with closed chanter, fitted with keys

6

Components of Lowland and Border Pipes

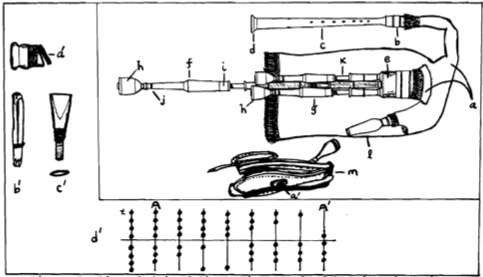

We can easily identify the components of the Lowland pipes shown in Figure 1 by studying the line sketch of the set shown in Figure 2. Knowing the terminology of these components allows us to make comparisons with other kinds of pipes.

Line sketch of the antique Lowland bagpipe shown In Figure 1: a) bag and bag cover; b) chanter stock; c) chanter; d) chanter sole; e) drone stock; f) bass drone; g) tenor drones; h) chalice drone tops; i) ferrules; j) simple combing; k) tuning slide; 1) blowpipe; and m) bellows.

Detail: a' clack valves on blowpipe and bellows inlet; b' cane single-tongue drone reed; c' cane doub1e tongue chanter reed - profile and end views; d' fingering diagram for the A scale. __________________

This sketch and terminology applies to the “generic” Lowland pipe but easily transfers to all the other bellows-blown bagpipe forms listed on the previous page. variations are found in the style of the components, such as the type of combing used on the drones (from none to elaborate) and the materials used for ferrules, drone top mounts (from plain wood to silver and/or ivory), tuning slides, etc. These cosmetic variations do not, however, determine the bagpipe types; this is possible only with information about the bore of the chanter, the drone tunings, and the “extra bits” such as regulators, foot joints, etc.

7

Descriptions

1. The Lowland pipe has been illustrated and described briefly. Older instruments were made from boxwood, blackwood, laburnum, or other native hardwoods. Popular pitches for the chanters are A and Bb, and are defined by the note obtained with all finger holes covered except the last or bottom one. The A chanter scale runs from G below middle C to A’ an octave above middle C. Likewise, the Bb chanter scale runs from nominally Ab below middle C to Bb’ an octave above middle C. An important feature of the scale is that the subdominant notes (G on the A chanter and Ab on the Bb chanter) are a whole tone below the dominant. This corresponds to the scale used on the Highland pipe chanter, and is different from the scales found on other European pipes such as the Breton Veuze or the Cornemuse de Berry. The chanter reed is usually a hefty wedge shaped cane reed which “crows” under a moderately high pressure and gives considerable volume to the conically bored chanter. The Lowland pipe tenor drones are normally tuned in unison an octave above the bass drone, which is made in three tunable sections. Older instruments had chalice-shaped drone tops mounted with ivory rings.

2. The Border pipe is functionally the same as the Lowland pipe described above, but generally has a narrower chanter bore, which means a thinner reed and mellower tone. Traditionally, the reed is thin enough to allow overblowing of the chanter- to obtain high B’ (on the A chanter). This was done by simultaneously pinching the bag with the arm and partially uncovering the thumbhole in a technique known in 18th century Scotland as “shivering the back lill”. Some of the Lowland and Border airs which benefit from accessibility to this high note are “The Soor Plooms O’Galashiels”, “Keelman Oer the Land”, “The Mill Mill O”’, and “Mary Scot, Flower of Yarrow”. In many cases the Border pipes were smaller and lighter than the older Lowland pipes, which may have facilitated singing and dancing whilst playing – a well documented skill of the master Border pipers. Some instruments have chanters whose length is extended by a foot joint. The longer chanter produces more mellow low notes and facilitates the overblow to high B’. Like the old Lowland pipe, the Border pipe has a bass drone and two unison tenor drones. In addition to chalice shaped drone tops, many instruments had thistle-shaped drone tops.

3. The Northumbrian half-long pipe has two notable differences from the Lowland and Border pipes: the chanter scale has a sharpened high seventh note instead of the natural and the drone combination is one bass, one tenor, and a baritone in between. The origin of the name “half-long pipe” is something of a mystery, especially in light of the fact that the instrument normally carries a chanter with a foot joint. Perhaps the name refers to the length of the bass drone, which, like the Border pipe is shorter than the old Lowland pipe. The author would appreciate any insights into this matter!

8

4. The Scottish smallpipe is the gem of the Scottish bellows pipes, being small, easy to control, delicately toned, and reliable. The pipes pitched in Bb sound much like the mouth-blown parlour pipes of the Highlands. The pipe may be found in a multitude of configurations, and to define a “traditional.” arrangement would be to limit the possibilities of the instrument. The basic instrument has a cylindrically bored chanter and three or four drones. Today the instrument may be obtained pitched in A, Bb B, C, D, and Eb. Through the use of up to six drones or interchangeable drone-stocks and metal keys, many musical key signatures are available to the player. Some instruments utilize closed drones fitted with tuning beads along the length as is done on the Northumbrian smallpipes.

Figure 3. Photograph of a modern set of Scottish smallpipes in Bb, made by Heriot and Allan. The set has bass, baritone, and tenor drones and two keys: one for high B’ and one for C-natural.

Figure 3. Photograph of a modern set of Scottish smallpipes in Bb, made by Heriot and Allan. The set has bass, baritone, and tenor drones and two keys: one for high B’ and one for C-natural.

____________________________

The Pastoral pipe is considered more fully in an Essay which appears later in this issue. Due to space limitations, the other pipe forms mentioned above will not be detailed here, but will be discussed further in the next issue. We also hope to explore the relationship between the Parlour pipes and the Scottish smallpipes more fully. I close this article on the next page with a truncated view of the lineage of Lowland and Border pipes. I invite your comments or additional information on the historical and anecdotal aspects of the Lowland and Border pipes.

9

Lowland~and Border Pipe Lineage

For the most part, the bagpipes of Scotland and England can trace their lineage to continental Europe and developed in response to local needs under continued European influence. It has been suggested that the smallpipes of Scotland and England are hybrid descendants of the native stock and horn, or hornpipe, and the continental bagpipe. The tree below summarizes this development. While it suggests a progressive and linear evolution, the reality was that of many parallel developments and personal innovations. The dates merely indicate early appearance of the stated form in literature or art to give historical context to the change. The chart focuses on on salient features of Lowland pipes and their derivatives – therefore, as we move down the tree, we leave behind many other notable pipes (e.g., Parlour pipes, Lancashire pipes, Welsh pipes, etc).

10

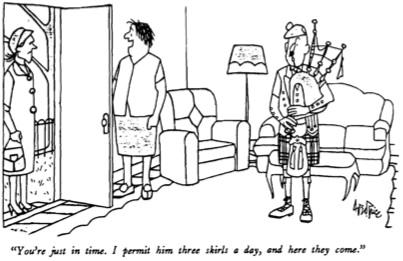

From The New Yorker, January 20, 1990 (Thanks to Bill Baron,

From The New Yorker, January 20, 1990 (Thanks to Bill Baron,

Newark, Delaware)

Cartoon by Mike MacNintch, member N.A.A.L.B.P.

Cartoon by Mike MacNintch, member N.A.A.L.B.P.

11

RECOLLECTIONS OF SCOTS SMALLPIPES by Sam Grier

I was pleasantly surprised at being asked to write “something” regarding Scots Small pipes. Actually, I was more surprised to hear that I was considered as a rarity. That is, to say, a smallpipes player, well past the age of fifty who has been playing for some fifty-odd years. I do not, even for a moment, believe that I am alone in the world, a sole survivor, so to say. I have known too many smallpipe players in my lifetime and they, and their pupils cannot all have passed away.

One very renowned piper and teacher – likely the most perfect pipe teacher since MacCrimmon, MacArthur, and “Chloinne N’am sgeulachd-Griogar”, was Archie MacNeill – the legendary “Blind Piper of Glasgow”. He tutored, literally, thousands of pipers of excellent quality. Archie was also a fiddle player and a bellows smallpipe player, and used to playing ceilidh dance bands in Glasgow and District. Originally from Ghia, he, as a boy, toured the highland games. He was infatuated with highland pipes and pipers. He was struck, he said, by the many different styles of playing. He quite particularly enjoyed the hotel scene after the games when people like James Center brought out and passed around their smallpipes. It seems most could play them. Archie taught many people “something of smallpipes” in later years, after losing his eye sight. Aside from myself, names that come to mind are Sydney and Walter Rose, his nephew Seamus MacNeill, and his son Alex MacNeill. There were, I know, many others.

Archie didn’t talk much about other pupils and unless you were in a class or boys brigade, you would never hear of them. Last year, after the smallpipes convention at North Hero, Vermont, which I thoroughly enjoyed and recommend, I went to Montreal and North Hatley, Quebec. I renewed many old acquaintances in the piping “Underground World”, saw Alan Jones’ impressive bagpipe collection, was enthralled by Richard Butler”s excellent recital on the Northumbrian Smallpipes, and met again, after many years, Alex MacNeill, the son of “Blind Archie”.

Alex, now 87 years old, sadly, is following his father’s footsteps in going slowly blind. He was a famous piper – much better than Seamus, in my opinion, Pipe Major of the C.N.R. and R.C.A.F. 401 Squadron Pipe Bands. He took Ceol Mor lesson from the also legendary Donald MacMillan of Dalibur, South Uist, pupil of John MacDonald Inverness, and is the inventor of the plastic practice and pipe chanter reed. I asked him what became of his father’s smallpipes with the 4-keyed chanter. He said, “Christ, I haven’t heard of them in years. I reckon Seamus has them with the rest of Dad’s stuff.” Someone should inquire about Archie’s smallpipes – they are quite valuable.

12

Another past excellent player of smallpipes is the celebrated accordionist, Bobbie MacLeod of Tobermory. His dance band played on the B.B.C. for years and made many records. He was both a highland and smallpipes player but gave them up in favor of the accordion. I don’t know if he had any pupils likely he did. He is still living and owns a hotel on Mull.

It is difficult to find smallpipes players. For the most part, they live quiet, almost secluded lives. Likely the only ones you will hear of are concurrently playing highland pipes in a pipe band and as a result, get around more.

I recently met again, an old piper friend at a wedding in Charlotte, North Carolina: Bert Smith, now living in Portree, Isle of Skye. Bert, like my grandfather lain McKenzie, used to play foot bellows smallpipes. Bert asked me if I had ever heard of Gordon Mooney. I said, “Yes, in fact, I have a tape of him.” Bert said, “Do you know I lived in the same town and directly across the same street as Mooney in Ayrshire, and never heard of him until after he made the recording?” I said no, but I wasn’t surprised.

Many years ago, I played highland pipes in the Detroit Highlanders Pipe Band under George Duncan and Walter Rose. At the time I lived in Windsor, Ontario and also played in the Essex Scottish Regiment Pipe Band. In those days (shortly after WWII), the top 3 bands in Eastern North America were the C.N.R. Band, Montreal, the Detroit Highlanders, and the Chicago Stock Yards Pipe Band. It may have been different, but many pipers lost their lives in the war. In going to compete at the highland games at Embro or Maxville, Ontario, we often took the same train as the Stock Yards Band. Incredible, unbelievable parties and incidents happened in both directions, on all trips. I could quite truly write a book – if I were sufficiently talented. Always, there were 3 or 4 sets of smallpipes – all different and most could play them all – and did. The best smallpipes player including myself, was “Barber Monty Montgomery”. He wasn’t a great highland piper, but he was incredible on smallpipes. I don’t believe I have ever, before or since, seen a piper raise his fingers so high on a chanter and play jigs and reels so crackingly. When Barber played a “strike” – it was well struck indeed!

During this time I was taking lesson from 3 teachers: Donald MacMillan, then living in Windsor, Walter Rose in Detroit, and Andy Adamson (Essex Scots) of Windsor. One evening, I asked Andy why he taught closed C’s when he himself played open C’s. He said it isn’t really correct on highland pipes and was a habit formed while playing smallpipes. surprised, I told him that I also played smallpipes. He then went under his bed and showed me his Scots Smallpipes with a 2-key chanter. He said he only played them at home since his wife “didn’t like the big ones”. Until then, I had no idea that Andy played smallpipes. I don’t think anyone else did either. Andy came from Stirling.

13

So, there are smallpipe players out there, of my age. I know there – but where …? As a matter of fact, some years ago I went to Denver, Colorado from Montreal. I started and taught a pipe band there, The City of Denver Pipe Band. I also taught the El-Jebel Shriners Pipe Band. No-one knew I played smallpipe, until I made a set of reel pipes and played then at a ceilidh. They were all surprised, non had ever heard them before and they were startled at the different drone and regulator sounds and combinations. I made a recording, as far as I know, it is the only one ever made of reel pipes. If anyone would like to hear it, simply send a blank tape and I’ll record it (Self-Addressed Stamped Envelope, Please). Also, I have a tape, from a wire recording, of Donald MacMillan – authentic, musical, old school, ceol mor.

On the subject of reclusive, concealed smallpipe playing… During the last few years, I have gone to and brought smallpipes to several highland games. On all occasions I have met and played with other smallpipe players – always way back in the car park. Only a few curious band pipes, returning to their cars, ever knew we were there at all – sad, really.

I, myself, would never had even known about the current revival of smallpipes were it not for Bert Mitchell, an excellent highland piper with whom I played. In his band, in Charlotte, North Carolina one night, Bert called me on the phone from Richmond, Virginia. He knew I played smallpipes, in fact I once loaned him a set. “Guess what”, he said, “now I know why you’re always looking for extra long chanters and prefer cane reeds! Have you ever heard of Hamish Moore?”· I said no, I hadn’t. Bert said, “I just went to a concert and he plays smallpipes like yours. I bought a record, I’ll send you a tape!” Bert made good on his promise, and I was delighted with the tape – the first I had heard in years of someone other than myself. I had come to thinking that perhaps I was all alone, after all. So it was a most pleasant happening for me. More than you could imagine.

At the time – 3 years ago – I had a pupil on Uilleanne pipes and I played the tape for him. He said “Hamish Moore? I’m going to an Uilleanne Pipes seminar next week in Elkins, West Virginia and Hamish Moore will be there the following week!” He agreed to call me from Elkins and give me a phone number to reach Hamish there. He did. I called. Hamish said that everyone was paying by cheque and he was therefore short of hard cash and would sell a set of pipes for cash. I drove up straight away, tried, liked and bought the pipes. We have been communicating ever since. Last year I again met Hamish at North Hero. He recently told me over the phone that he will be there again, next year – so will I!

14

It would seem there have always been pipers and fiddlers in my family. My own father did play smallpipes. My other grandfather played reel pipes with a foot bellows. Also, I had uncles and cousins on both sides who played both highland and smallpipes with foot or arm bellows. While I never mastered the foot bellows, I must say here that in the case of pipes with regulators (ie. Uilleanne, pastoral, reel and chamber pipes), the foot bellows are superior since the regulator arm is free, permitting much easier access to the keys.

I see that I have raised a question here. What is the distinction between these four types of pipes? The Uilleanne and Pastoral Pipes are nearly identical to each other. The drones are the same, usually three, pitched 2 octaves, and 1 octave below the fundamental with the small drone pitched on the fundamental. On both types there is usually – but not always – a drone switch to start and stop the drones in unison, and to tune the regulators. On some sets, of both types, there is a fourth drone pitched usually on the fifth above or below the fundamental. This drone frequently has a long tuning pin and slide and can also be tuned to the fourth interval. It usually has a separate drone switch so it can be pre-tuned and turned on or off at will, providing a very pleasant harmonic. The large of double bass drone on the Uilleanne pipe is folded, trombone-like, outside the drone stock while on the pastoral pipe, it folded inside the drone stock by connected bores, and an upward crook where the reed is seated. This latter feature,’ the inside folded double bass drone, has induced many people to say that the Pastoral Pipe is the ancestor of the Uilleanne Pipe. This may or may not be true. There is as much evidence to dispute, as to support this theory. I, myself, have seen and played older, short chantered, Uilleanne pipes with only 2 regulators and an inside fold double bass drone. I have also heard of, but not seen, a Pastoral pipe with 2 regulators. It is very likely both instruments have a common ancestor. But, of chickens and eggs, we will never know. Both instruments are sometimes called “Union” Pipes.

I will tell you what I have heard of this. Makers of Pastoral pipes in Scotland at the time of the Treaty of the Union in 1707, when the thistle became the emblem of Scotland, obsessed with patriotism, changed the drone top design, making them in the shape of a thistle flower – only these were call “Union” pipes. The former name was the same, both in Scotland and in Ireland, and it was: “piob Balb-S’eididh Cas” – foot bellows pipe, or treadle pipe, and “piob Balb-S’eidih Uilleanne” – elbow bellows pipe. One other word was placed at the end of the name – “Beag” (small); “Meadenach” – middle; and “Mhor” (big) – never “Mor”, since that is the feminine of “Mhor” (“M” is pronounced as, M and “Mh” is pronounced as, V). In the case of Pastoral or Uilleanne pipes, the word “Meademach” was used since they were considered to be middle sized. Border and Reel pipes would also be in this category. As regard to regulators, the Pastoral pipe has only one, traditionally, with 4 keys. The great difference in the two is the chanters – the Pastoral chanter is much longer with a

15

separate foot piece and is laid on the right side of the right thigh in playing position. The sound is quite different, more mellow than an Uilleanne chanter, and it is not moved, or stopped, to jump the octave. Also, the reed is very much different in size and shape. The fingering is quite similar to Highland pipes while the Uilleanne fingering, is similar to flutes and whistles. Both play 2 octaves “and a bit”, and are cross-fingered for sharps and flats although the Uilleanne chanter is frequently keyed for this. The Uilleanne pipe is made

in the keys of B flat, C and D, while the Pastoral is in D and E minor.

An observation here: most smallpipe chanters are cross fingered to obtain sharps, and flats, – to conform to various drone tunings – and to go from legato to stacatto styles of fingering, both are usually played. Some where along the line, this logic has been lost in much Scots smallpipering that I have heard lately. Modern Scots smallpipe players are simply using Highland pipe fingering. This really will not at all “get it”! I am fully cognizant of what is called “correct fingering” closed C, open low G and open upper hand etc. Smallpiping required considerably more than this (ie. closed C sounds quite horrid if you have even only one drone tuned to B or D in the key of A, for example, a thing that was frequently done). with a properly set chanter reed, depending on the key utilized, you will play a closed low G for E, and some notes above, usually every other note. In the case of D drones in the key of A,· you will raise only one finger to play F, and etc, etc, etc. While it is imperative to learn fully, Highland pipe fingering, it is only the beginning, there’s more. In fact, there’s music! The Highland pipe is limited to 9 notes, 2 drone sounds in octaves to the fundamental and a rigid fingering pattern for each note. There is almost no possibility for virtuosity for the performer because of 1) rigid inflexible attitude of judges and teachers, and 2) the entire logic of the pipe band – 12 pipers sounding like one. The only way to discern a virtuoso here, is to determine who can keep good time and tone, on a solo basis, with a greater and greater degree of fingering dexterity to the point of ridiculous complexity. The end result is nothing more than proficiency in playing very complicated exercises. Still, the same nine notes. Rather boring still, the same two drone sounds. Tedious indeed. The only opportunity for individual expression is in the original art – that of “Ceol Mor.”

Sadly, though, the judges have, with their rigidity, slammed the door shut here as well – Ceol Mor doesn’t sound nearly as musical as I can remember. In fact, it doesn’t sound good at all anymore. Small wonder Highland piping needs so much color, pageantry and cultism. Happily, some pipes are playing in ceilidh bands and groups and a few pipe majors are starting to utilize some smallpipe fingering tricks. So there is hope! I can easily remember when highland pipers playing Ceol Beag and Ceol Meadenach, played like fiddlers. Let’s hope for that again!

16

I see I have rattled on here for quite some length. I’ve only lightly discussed two or three instruments. If you, the reader, and you the publisher are foolish enough to desire it, I will discuss the reel and chamber pipes in the next issue.

Sam Grier playing his Pastoral Pipe in front of the Town Hall, at North Hero, Vermont, August 1989.

Sam Grier playing his Pastoral Pipe in front of the Town Hall, at North Hero, Vermont, August 1989.

17

LOWLAND BAGPIPES AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART by Mike MacNintch

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, has a large collection of bagpipes. Due to the lack of room, only a few of the sets are on permanent display, but arrangements can be made to view the other sets through the curator. Among the pipes in this collection are several sets which pertain to our interests, as they fall in the Lowland and Border category.

The first of these sets is an 18th century Scottish Highland smallpipe. This is the Highland counterpart of the more familiar Lowland instrument. They are mouth blown, and the blowpipe is tipped with horn. The rest of the set is mounted in ivory, bone, and horn. There are three drones in a common stock, each being in two pieces. They are a bass, treble, and tenor. The bag has a cover of brown corduroy with green trim.

There is a set of Lowland pipes which date back to the 19th century. It has three drones which are mounted in a common stock. The bass drone is in three sections, and the two tenor drones are each in two sections. They are mounted with ivory and the bag is covered in tartan.

There is a strange set of pipes classified as being a Lowland pipe because of a bellows. This set is peculiar in that it has three drones that are each in separate stocks. The drones are a bass, in three sections, and two tenors, each in two sections. They are about the same size as a regular set of Highland pipes. It is possible that this is a modified Highland pipe. Another possibility is that this is a Lovat Reel pipe, but they are too large for this. They are dated to the 19th century.

One set of Highland pipes is on display, and they are a typical example of the modern Highland bagpipe. The set is marked “R. McKinnon, Glasgow” and is thought to have been made between 1887-1902. The mounts are of ivory and the blowpipe has a horn tip.

Two sets of Northumbrian pipes are in the collection. The first set was made before 1837 by Robert Reid of North Shields, Northumberland. The chanter has six keys, and the four drones are mounted with brass and ivory. Each is in two sections. The other set was made after 1867 by J. center, of Edinburgh. They are similar to the first set but the chanter has nine keys.

There are also two old sets of Uilleann pipes. The first set has no drones left but the chanter is narrow and conical. It has seven brass keys and dates from the 18th century. The other set was made in the 19th century and the bellows is marked “J. Sharp, Aberdeen”. As in the other set, the chanter is narrow and conical. There are two drones.

18

There is a bass regulator in three sections, with four keys, and two treble regulators, one with four keys and the other with three.

Bagpipes from all over Europe and Asia are well represented in this collection. There are a large number of French pipes in particular. Photographs of the instruments are available from the museum’s photo sales department. Regulations that govern access to the collection for study purposes can be obtained on request. For more information, write to the address below.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Department of Musical Instruments

New York, New York, 10028

Mike MacNintch playing a set of Border Pipes made by John Addison.

Mike MacNintch playing a set of Border Pipes made by John Addison.

19

ESSAY by Brian McCandless

WHICH CAME FIRST… THE PASTORAL-UILLEAN PIPE PROBLEM

It seems quite certain that it will be possible to determine large areas in which, by diffusion, similar types of musical art have developed and in which, by subdivision local types may be segregated similar in character to those found in decorative art. Even in the modern folk music of Europe a definite character of the folk music of each nation may be recognized. Borrowed melodies adapted to local forms illustrate this type of individuality.~

Franz Boas, 1955

In his seminal work, Primitive Art, Franz Boas laid the foundation for the logical analysis of cultural diffusion through the recognizance of ritual and decorative art forms in so-called primitive societies. His brief allusion to folk music in primitive society tempts us to wonder if logical solutions may be found for “modern” society. In particular, might we resolve the raging debates that have hounded English, Scottish, and Irish bagpipe authorities for the past century? Can we ever hope to codify the evolution of Scottish and Irish bagpipes in a way that is consistent with concomitant changes in Scottish and Irish culture and in a way which is inoffensive to the ethnically sensitive?

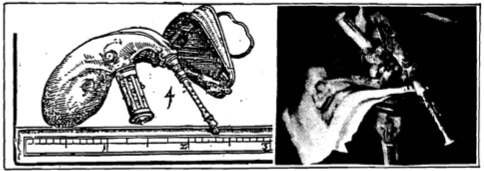

As a case in point, I invite you to pursue the controversy concerning the origin of the Scottish Pastoral and the Irish Uillean pipe. And an interesting case it is, for while we have no timely treatise on the matter, we can find museum collections, photographs, and woodcuts showing early examples, and as you can see in Figures la and b below, a great deal of similarity exists between the early forms of the two instruments. There are two basic positions on the subject. On the one hand Scottish authors claim that the Uillean pipe descended from the Pastoral pipe which itself was descended from the Border pipe. On the other hand, Irish authors have variously claimed that the Pastoral pipe and, in fact, all Scottish bellows pipes descended from the Uillean pipe! The most offensive of the Irish authors in this regard were Grattan Flood and Francis O’Neill, writing around the turn of the century, at a time when Irish nationalism was at its highest tide since the Battle of Carlow. One never reads the possibility that they were parallel developments fostered by developments in musical instrument construction throughout Europe… but I am ahead of myself.

20

Figure 1a. Photograph of an early example of a Pastoral pipe (from Bagpipes, by Baines, 1960) .

Figure 1a. Photograph of an early example of a Pastoral pipe (from Bagpipes, by Baines, 1960) .

Figure lb. Photograph of an early Uillean pipe, by Egan (from The story of the Bagpipe, by Gratton Flood, 1911).

Figure lb. Photograph of an early Uillean pipe, by Egan (from The story of the Bagpipe, by Gratton Flood, 1911).

21

In addition to the divergent claims there is the business of Geoghegan’s Tutor, published for the “Pastoral or New Bagpipe”. It was a tutor published in 1750 in London – neither in Scotland nor in Ireland – containing a treatise on playing and containing 40-odd melodies bearing Scottish, English, and Irish names. The Irish, however, continue to claim the book for their own Uillean pipes, despite the fact that the Uillean pipe, even in its earliest documented forms was not capable of playing C below bottom D, which is a feature of the Pastoral pipe – the subject of the tutor. Interestingly, the Tutor contains no mention or illustration of the regulator and even shows the instrument being played by a fellow standing in a garden. Do we assume then that the Pastoral pipe of 1750 had a two octave range but lacked a regulator?

Which, if either, came first then – the Pastoral pipe or the Uillean Pipe? Why is it so important?

We can shed some light on the first question only by discarding our ethnic prejudices and considering the Pastoral and Uillean pipes in their cultural contexts. One problem is that these same ethnic prejudices are responsible for our very interest in the instruments. The question is important to us because we seek clarification of all aspects of our sacred old instruments and we wish to place them in a socio-historical context which fits our own idiom. This creates a dilemma, a kind of ethnic conflict of interest: our ethnic predisposition leads us to a particular instrument or musical form in the first place, then we embrace the form as part of our cultural heritage. As we begin to acquire background information regarding our instrument, we tend to reject details which conflict with our viewpoint. Eventually, we form a romanticized view of our chosen instrument’s original context which does not have a basis in reality. In the absence of a written record, the romanticized view wins out, leaving the world-at-Iarge with at least one exaggerated and inaccurate if not totally false story. Thus, by not going at the problem, we allow the continued perpetration of myths.

Lacking a written record, Boas’ framework offers us a way out, by causing us to examine the forms of the instruments themselves and the musical repertoire intended for or adapted to the instrument. With this form framework in hand, we can step back to European and British society of the 17th and 18th centuries and determine the contexts and influences, such as, among the instrument makers, who was borrowing from whom?

So now we turn to the pipes themselves. In the Figures above are photographs of an early Pastoral pipe and Uillean pipe. Notice how both instruments are fitted with a short straight drone, a long folded drone, a single four-key regulator, and a chanter at the end of a long bag neck. A fundamental difference between the two, however, is the chanters themselves. The Pastoral pipe chanter resembles a Border pipe chanter but is even longer and thinner. The Uillean pipe chanter is also long and

22

thin, but lacks the foot joint of the Pastoral chanter. The foot joint would allow the Pastoral piper to execute, say, a Highland type birl movement. In this regard, Geoghegan says:

"the Sound of them almost plainly expressing the Word, the first

and chiefest Curl is perform'd by the little finger of the lower

hand on the Chanter which is done by doubling the little finger, on

the lower hole, this Double is done by a moving the finger to and

fro on the lower hole it performs the sound of two Quavers which

when a Man is Master of doing and playing a few Tunes he will be

able to give several Graces therewith."

Geoghegan's Tutor, 1750

The movement described is a birl and is a characteristic gracing in Scottish pipering. This movement is possible only by virtue of an open-ended chanter possessing a sub-dominant note played with the little finger. The Uillean pipe, with its altogether different design, denies the piper access to the birl, since the lowest note on the chanter is also the dominant. Instead, the Uillean pipe invites the Cran, a movement or “Curl” using notes above the dominant. The technique is described by O’Farrell writing a little after Geoghegan in his “Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes … a Treatise with the most Perfect Instructions ever yet Published for the Pipes”:

" ...The Curl in the first Example being a principle one on the Pipes

is perform'd by sounding the Note D [bottom note of the chanter -

author's note],by a sudden patt of the lower finger of the upper hand,

then slurring the other Notes quick and finishing the last Note by

another patt of the lower finger of the upper hand."

O'Farrell's Treatise, 1767

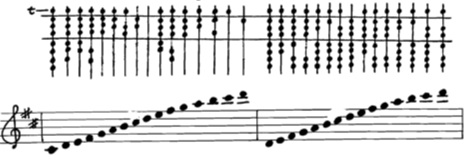

Aside from the value of the lowest note, the two pipes share exactly the same musical scale – although manual execution of these scales are dramatically different:

Figure 2. Direct comparison of the musical scales of the Pastoral (left) and Uillean (right) pipe.

Figure 2. Direct comparison of the musical scales of the Pastoral (left) and Uillean (right) pipe.

23

In bore dimension, shape, and reeding, the two pipes are very similar. Also, the way in which the upper octave notes are reached is basically the same – the bag is pinched tight at the right moment. On the Pastoral pipe, the long foot joint makes the jump more or less automatic, while on the Uillean pipe, the chanter is sealed on the knee, allowing a slight back pressure to develop which forces the reed to overblow. The result is that the same piece of music could be played on either pipe (bearing in mind the differences at the bottom end) but would take on slightly different qualtites, especially around the octave change where, on the Pastoral pipe it would always be played legato, but on the Uillean pipe it could be played legato or stacatto. Thus there is a degree of musical freedom found on the Uillean pipe that would not be possible on the Pastoral pipe – stacatto or pop-note execution. I have heard the theory proposed, based on this argument, that the Uillean pipe in fact is a descendant of the Pastoral pipe. By eliminating the foot joint, the chanter could be played “on the knee”, thereby allowing staccato execution and more reliable octave transitions.

On the basis of simple chanter analysis like this, we can propose an evolutionary line that begins with the Border pipe, evolves into the Pastoral pipe, and culminates with the Uillean pipe. This argument seems fine for the chanter alone, but what about the regulator – Geoghegan says nothing about it – which makes it an integrated instrument of melody, drone, and harmonic accompaniment that ” …almost ceases to be a bagpipe and is now quite akin to an organ”?

To address the regulator, we must understand the regulator’s function. Beyond the basic formula of melody against static drone, the regulator allows the performer to create chordal accompaniment to the melody at will. This type of accompaniment was not what the auld music was about – it was a response or joining to the “new” Baroque music developing in the cultural centers of Europe. This regulator and its function were no leftovers from the skirling Highland muster calls or lunch-hour alarms of the Border Waits! Together, the two-octave chanter and the regulator made the old music new, fed the creation of new tunes, and thus allowed the performer to play the “vogue” melodies of a changing time. The regulator and increasingly more convoluted bass drone lent the old instrument just the right degree of technical sophistication to catch the eyes and ears of the “post O’Carolan” era gentlemen who needed just that kind of musical diversion.

But let me explain. If you would, throw your mind back to the early days of the pre-industrial revolution in Britain and Europe. Amongst the general population, those not able-bodied enough to work in the fields, mines, or mills, often earned a meagre living by playing music – country music, mixed with some original music of their own. Their lot is well documented in the numerous etchings and paintings of the 17~ and 18~ centuries many of which are obvious mockeries of the lives of these poor

24

people. In 17th century Ireland and Scotland, the bagpipe, harp, and hurdy gurdy were the minion of the tinker, the pauper, and the itinerant musician. If a musician were talented enough, he might earn the praise and financial support of a patron. Turlough O’Carolan, the blind Irish 17 century harper and James Allan, the 18~ century Lowland and Northumbrian piper, come to mind.

By the early 18th century, though, in step with changing socio-political events on the European continent, bagpipes everywhere were increasing in popularity among the aristocracy where they reached courtly status. For the gentry, who spent a great deal of effort and money in emulation of high society, this meant “a call to pipes” as they sought out the same respectable pleasantries and pastimes as those of the Courts, spawning what might called the Great Age of Amateurs – from music to science. With more than a handful of aspiring “drawing room” musicians scampering around for whatever social status they could find, competition for “the latest” in “fashionable” and lavishly executed instruments grew fierce. In the case of the hurdy gurdy, so great was the demand that the best makers resorted to tearing apart 16th century lutes for the frames to construct new hurdy gurdies. And they achieved a gawdiness never before imagined!

In bagpipe land, both on the continent, and in Britain and Ireland, gone were the days of the simple mediaeval pipe. In the Highlands, nationalistic fervor elevated the Great Pipe, with its thunderous drones, to the cause of the Pretender. In France, the musette was fitted with keys to extend its chromatic range, making it a true “gentleman’s” bagpipe. From 1600 to 1690, experiments led to development of a musette with shuttle drones and a petit chalumeau which was silent unless a key was depressed – a regulator – transforming the instrument from a bagpipe to a socially acceptable pseudo-organ. It was dainty and quiet enough that “the ladies were encouraged” to play it!

Figures 3. Early Musette (left) according to Michael Praetorious (1619) and detail of later Musette du Cour according to Jean Baptiste oUdry (1742).

Figures 3. Early Musette (left) according to Michael Praetorious (1619) and detail of later Musette du Cour according to Jean Baptiste oUdry (1742).

25

What I am proposing is that herein, in the court instruments of Louis the 14th, were the inspirational elements for the nearly simultaneous development of the high forms of the Scottish Pastoral Pipe and the Irish Uillean pipe, derived from the old Lowland or Border pipe. The instruments’ popularity must have been staggering, for they were available in all the major cities: Dublin, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and London. In this light it is easy to see that, taking their lead from France, adding regulators to existing bagpipes was “the thing to do” to bring both the technical level of the instrument and the playing level of the performer up to the standards of the day.

Eventually, all fashions pass, and from the heyday of aristocratic nurturing, the exquisite bagpipes and hurdy gurdies produced during the 17th and 18th centuries passed into the obscurity of middle class wasteland. By 1800, though, many instruments, by way of personal sale or public auction, found their way into the ranks of the lower classes where they have remained until only recently. In Ireland, the Uillean pipe took off in popularity among all social classes and was carried to North America where the instrument was further refined by Taylor in Philadelphia. During the years 1800 – 1900, the Uillean pipe reached its current level of development, multitudes of tunes were written and collected, and playing techniques and styles were passed along and refined, culminating in the genius of such players as the Rowsomes, Bernard Delaney, Patsy Touhey, and later, Seamus Ennis and Willie Clancy. Victorian Britain, on the other hand, homogenized and redefined Scottishness to mean Highland, with overemphasis placed on the Highland pipes, Highland dress, and Highland music at the expense of other Scottish pipes and traditions. Highland piping, however, became well codified and regimented for the armed forces of the Crown of Britain. While they never “died out”, the Pastoral and Border pipes passed out of popular culture and many tunes and instruments were lost. The Pastoral pipe essentially went the way of the Clipper ship. Today, it is a joy to meet people like Sam Grier and to see players and makers reviving the instruments and tunes in a rekindling of the traditions of this beautiful old instrument.

26

REVIEWS

THE FIFTH ANNUAL NORTHUMBRIAN PIPER’S CONVENTION

August 25-28, 1989, North Hero, Vermont

Some semi-serious notes…Semi-serious because life is too short to be serious all of the time. This fete is the perfect place to let off steam and really enjoy yourself in bagpipe heaven! Pipes and pipers literally crawl out of the woodwork here. It is possible to see and hear instruments that you never knew existed in North America, let alone survived or existed at all! Each year there are new surprises, and last year was no exception.

The convention is held in and around the town hall of North Hero (Don’t blink! You’ll miss it!) Vermont. The town is on North Hero Island, in the middle of Lake Champlain. The setting of this tiny town, and the countryside around it, is rather “pastoral”, and therefore very appropriate for bagpiping of any kind.

Friday night marks the start of the convention as pipers gather at the Shore Acres Inn for supper, sessions, and socializing. The session began on the Irish side of things with master Uilleann piper Tom Creegan at the center of attention. Actually, he was almost behind this large potted plant! Later in the evening we were treated to some fine Northumbrian piping with resident instructor Richard Butler, Lance Robson, Frank Edgely, Neal MacMillan, and many others. A highlight of the evening were Alan Jones’ new toys – two new sets of pipes made by the French maker Remy Dubois. They were both bellows blown, one being a Bechonnet Musette, and the other a Cornemuse Flamande. I was able to try one of the sets – it played like a dream! Another highlight was an antique set of Glen Parlour pipes brought by James Coldren.

Saturday morning, everyone got down to the business of taking Northumbrian classes with Richard Butler and Lance Robson. Well, not everyone. Some others bought records, talked, played, checked out one another’s pipes; in general, messed about the way pipers and other musicians like to do. Hamish Moore took up residence in one part of the hall making reeds and had several nice sets of smallpipes for sale. There were people outside playing on the front lawn as there have been every year, and in the basement, harpers, whistlers, and Uillean pipers conducted workshops.

Saturday night the dance took place in the hall. I was lucky enough to get some Breton dancing in before things really opened. Daniel Thonon and friends were warming up on hurdy-gurdy, accordion, and pipes. The first dancing of the evening was a mix that could best be described as Northumbrian / Scottish country / contra / square dancing. Music was provided by Richard Butler and friends. Next, there was Acadian music, played on two fiddles, harmonica, whistle, and feet. The whistle player set new standards! He was nothing short of incredible! The caller was Pierre Chartrand, and he did some of his great

step dancing, sometimes even as he called the dances! The dance ended in usual good form with Breton and French dancing with

27

music provided by members of the group “Ad Vielle Que Pourra”. One cannot sit still during these dances! Everybody was on the floor to do the gavotte, waltz, an dro, hanter dro, polka, and bourree.

Sunday morning, groggy but enthusiastic convention goers come back to the hall to continue classes. Mike MacHarg and his family had their shop set up, with piping supplies and plenty of instruments for sale. In addition to the Northumbrian classes, there was an Uillean pipe reed making workshop, and a Lowland pipe workshop conducted by Frank Edgely. Yann Plunnier gave a talk on Breton music, and told us all about how Highland pipes came to Brittany.

Sunday evening was reserved for the grand concert, and last year’s concert was probably the biggest yet. Among the more well known performers, there was Richard Butler on Northumbrian pipes, Billy Jackson (Ossian) on harp and whistle, Hamish Moore on smallpipes and the familiar Highland pipes, and Tom Creegan and Al Purcell on the Uilleann pipes. Other performers inclUded Lance Robson, on his antique silver and ivory Robert Reid Northumbrian pipes, and Sam Grier on a beautiful sounding set of pastoral pipes, made by John Addison. Frank Edgely and family played some lively music on half long pipes, guitar, harp, and fiddles. Brian and Michele McCandless with Steve McLain played Lowland and Irish music on Scottish smallpipes, guitar, and flute. Balkan music was played by Mark Gilston on his Gaida and Cimpoi, and the evening was finished with myself and Burt Mitchell on Highland pipes.

Sessions are a big part of the convention, and last year saw two of note. One was a French Canadian session which took place after the dance on the front porch of the hall. Another was an impressive seven Uillean pipers playing together in the basement, a sight not often seen.

Monday morning, what few people are left gathered to clean up and finalize things. Usually a group picture is taken on Sunday, but this year it was Monday morning. North Hero is a hard place to leave!

As the reader can see, this convention is not just for Northumbrian pipes. Almost anything can be seen here. In the future, Lowland and Border pipes will be promoted more. As a matter of fact, Scottish smallpipes are probably just behind Northumbrian pipes in number. This year the convention will take place on the 24th through 27th of August, 1990. Those who want more information should contact Alan Jones at the following address; P.o. Box 130, Rouses Point, New York, 12979, USA. Phone for 1990 only, 514-674-8772.

—- Mike MacNintch

HAMISH MOORE LOWLAND PIPE WORKSHOP, 1989

The first annual Lowland pipe workshop in North America, conducted by Hamish Moore at the farm of Matt Buckley, in Richmond, Vermont, was held the week of the 21st of August, 1989. Approximately ten students were in attendance at the event, which ran until the start of the Northumbrian Pipers’ convention in North Hero, Vermont. The students were divided into three groups according to their needs and abilities. The mornings were taken up with classes, giving emphasis to bellows technique, ornamentation, and repertoire. After lunch, people were coordinated for solo, duet, and trio playing, with emphasis on harmony playing. Late afternoon forum discussions were held on such diverse topics as cauld wind piping history and the Cape Breton place in Scottish musical history. Making music with others was a dominant theme, culminating in evening sessions. People who attended enjoyed a useful week of pipering in a beautiful rural setting. At the time of this pressing, the second workshop is being held. If you are interested in attending next year’s workshop, please contact Matt Buckley, PO 1 Box 276, Richmond, Vermont 05477.

– Compiled from dispatches

LOWLAND PIPES WELL REPRESENTED AT EVENING OF BAGPIPES

The evening of February 17, 1990 saw a unique event in American piping, a piping ceilidh at the Polish Workers’ Hall in Bensalem, New Jersey, sponsored by James Coldren. The event involved some twenty pipers who displayed and performed a diverse array of bagged instruments, ranging from the Scottish smallpipes and Musette de Cour to the Highland pipes and Grosserbock. The approximately 70 people in attendance enjoyed a spectacular display of new and historic instruments followed by a three hour performance of solo, duet, and trio pipering. Notable performances were given by Linda Currie and Francis Wallace on Scottish smallpipes in D, by Mike MacNintch and Tom Childs playing Scottish smallpipes in D, George Martin playing Parlour pipes, and Edwin George playing an antique Musette de Cour and a Grosserbock. Other bagpipes demonstrated were the Northumbrian smallpipes, the Breton Veuze in combination with the Pibole, the German Schaeferpfeife or Dudelsack, and the Spanish Gaida. Many of us who played and listened that night hope to coordinate more mUlti-piping events such as this one. Thanks James!

BAGPIPE WORKSHOP AT BALTIMORE FOLK MUSIC FESTIVAL

The Baltimore Folk Music Festival, held on March 24, 1990, featured an hour-long bagpipe workshop. Brian McCandless spoke on and demonstrated the Scottish smallpipe and the Border pipe for an audience of about 20 people. Uillean pipes, Highland pipes, and various East European pipes were also represented.

29

MUSIC REVIEW

Gordon Mooney, O’er the Border-Music of the Scottish Borders

Played on the Cauld Wind Pipes, Temple Records, 1989.

With this album, Gordon Mooney has brilliantly executed a musical montage of Lowland and Northumbrian pipering that weaves through three hundred years of piping tradition. From the light hearted “High Road to Linton” set through the winnowing “Bonnie Milldams of Norham” to the wildly inspiring title track we are magically transported across the sea to the windswept Border country. This timely and priceless collection sets the Lowland pipes in their traditional context both as a solo instrument and as accompaniment to the sad, beautiful songs of an earlier time. Gordon is accompanied on various tracks by his wife, Barbara on Flute and Bassoon, Nigel Richard on Mandola, Robin Morton on Bodhran, Brian Miller on Guitar and Mandolin, Alan Reid on vocals and keyboard, Douglas Pincock on whistle and flute, Jo Miller on vocal, and Charlie Soane on fiddle. The pipes Gordon uses on the album are Scottish smallpipes in D by Colin Ross, Scottish smallpipes in A by Robbie Greensitt, Northumbrian smallpipes in D by David Burleigh, Northumbrian smallpipes in F by Gordon Mooney, and Border pipes in Bb by Gordon Mooney.

All of the music presented is traditional. Many of the tunes may be found in Gordon’s “Collections of the Choisest Scots Music…” and in his “Tutor for the Cauld Wind .pipes”. Side A opens with a solo set of three old tunes on the Border pipes in A, two reels (“Willie Allan’s Fancy” and “Jimmy Allan’s Fancy”) and a 9/8 jig (“Wee Totum Fogg”). Two hornpipes follow, played on the Scottish smallpipes in D, accompanied by flute and whistle. A song, “The Twa Corbies”, pitches the Scottish smallpipes playing in Em with the beautiful voice of Jo Miller and harmony vocals by Alan Reid. The song is framed by the haunting “The Bonnie Milldams of Norham” and “The Last Cradle Song”, performed in set with the bouncy reel, “Duns Dings A”’. The side ends with a spectacular arrangement of “O’er the Border” recalling the days of armed raids by the Border reivers.

Side B again features a solo piping performance, but this time with Border pipes in Bb playing a set dedicated to the old droving trade and framed at beginning and end with the reel “The Highway to Linton”. After a set of ballad airs, Barbara Mooney’s Bassoon is effectively combined with the Northumbrian smallpipes on the air to the song “Willie’s Drowned in Yarrow”. Next, the song “Lord Randal” which was mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in his “Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border” is performed with the singing of Jo Miller, Northumbrian smallpipes, and keyboards. Two sets using the Scottish smallpipes finish the side with plenty of old Border tunes.

The album contains a superb booklet describing the music of the Borders, collectors of Border music, Border bagpipes, and each of the tunes and songs in considerable detail. For the enthusiast of Border music and history, this album is a uniquely enjoyable experience.

—- Brian McCandless

30

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

This is a partial list of recordings since 1977 that have included or featured Lowland pipes. If you are aware of others that have been overlooked, please let the Editor know so that the list can be maintained as accurately as possible.

Bagpipe Code

1 – Border pipes, 2 – Scottish Smallpipes, 3 – Pastoral Pipes, 4 – Parlour Pipes,

5 – Northumbrian Smallpipes

31

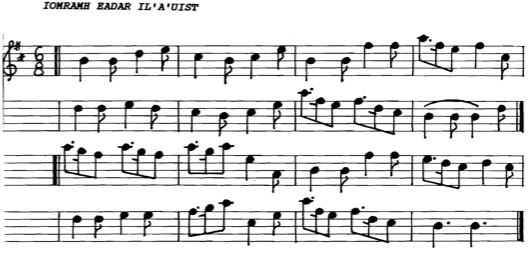

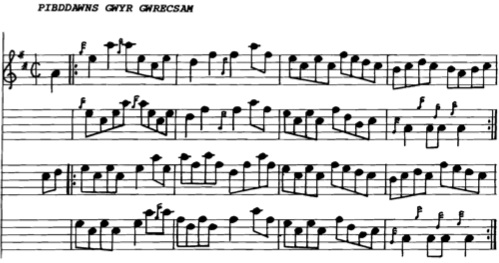

TUNES

We present settings for eight tunes that play well on Lowland pipes and Scottish smallpipes, representing a variety of ethnic traditions: four are associated with the Border regions of Scotland, one is Hebridean, one is Irish, and two are popular Welsh dance tunes. The scale adopted for presenting the tunes is that of the Border chanter in A, running from low G to A above middle C. The settings are sparsely graced, leaving final arrangement to you.

Two of the tunes, “A Scotch Measure” and “Chark’s Hornpipe” are from Geoghegan’s “Compleat Tutor for the Pastoral or New Pipe” (c.1750) which was kindly provided to the editor by Alan Jones. The Pastoral pipe scale runs from low C through two octaves to D.

NOTES FOR THE TUNES

1 – A BORDER BALLAD: also known as “Waly, Waly” and related to the tune English folk song “The Water is Wide”. The music was kindly contributed by Michael MacHarg. The setting and seconds are adapted from an arrangement by played by the Mystic pipe Band, Mystic, Connecticut.

2 – GALLOWA’ HILLS: a beautiful air to the song with the same name recalling the beauty of the Galloway district of southwest Scotland.

3 – A SCOTCH MEASURE: a melody found in Geoghegan’s “Tutor for the Pastoral or New Bagpipe”. with minor adaptation the tune plays well on the nine-note chanter.

4 – CHARK’S HORNPIPE: a 3/2 hornpipe found in Geoghegan’s “Tutor”. Due to the two octave range of the melody, it is intended for performance on the Pastoral pipe. The 3/2 meter is characteristic of 17th century Scottish hornpipes.

5 – THE WILD IRISHMAN: Adapted from the popular Irish session tune.

6 – IOMRAMH EADAR IL’A’UIST: the tune from a Hebridean folk song titled “Rowing From Islay to uist”.

7 – MEILLIONEN: a Welsh set dance tune. “Meillionen” is the Welsh word for “Cloverleaf”, which relates to the figures in the dance. The fourth bar of the second part uses the high “B” note, which can be executed on most Border pipes (known as “shivering the back lill) and on Scottish smallpipes fitted with the B-key. If your pipes cannot play the high “B” note, then substitute high “A” and play a doubling with the adjacent high “A” notes.

8 – PIBDDAWNS GWYR GWRECSAM: literally, the “Wrexham Men’s Pipe Dance”. Wrexham is a town located in near the Wales-England border just south of Chester.

32

33

34

35

SOME NOTES ON TUNE EXECUTION

Generally, players of the Highland pipe have little difficulty in arranging and performing expertly on Border pipes and Scottish smallpipes. However, the “standard” Highland settings for the tunes are not always the most pleasant sounding on the Lowland pipes and in some cases, the pipes and reeds themselves will not allow the performer to crisply execute Highland movements, for example, a grip. This is because the reed overblows due to the change in acoustic impedance from the E note to the low G note. Coping with this situation means altering the setting, usually by substituting a single grace note for the movement.

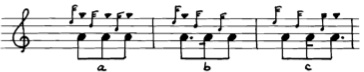

Players of the Lowland pipes ought not feel restricted to playing Highland tunes and settings. Plenty of Lowland and Border tunes exist (see Reference Section), and the instruments are very suited to playing a diversity of musical styles. As we are not aware of a codified system for playing and gracing tunes on the Lowland and Border pipes, we feel that it is quite acceptable and even advisable to experiment with techniques borrowed from other piping traditions. Here are some examples to tryout with gracings on low A:

Highland techniques include the Birl (a) and the G-D-E gracenote sequence (b). A modified Uillean pipe Cran (c), using a E-D-C sequence may be used. “Popping” the chanter (d, e, f, and g) repetitively with either A, G, F, or E gracenotes can be used to produce a light-hearted effect, but may result in overblowing of the reed.

If you are playing a multi-note movement, you should give thought and practice to the emphasis of the notes in the movement as indicated below for an E-D-C sequence of gracenotes on A. A “rounded” sound results when all three notes are played with equal duration or emphasis (a). A “clipped” or more serious effect is achieved when the first, or E note is emphasized (b). A “galloping” effect occurs when the last, or C note is emphasized (c).

SHORT NOTES

~ Michael MacHarg sent us two recipes for bag seasoning:

1. a mixture of 50% Beeswax to 50% olive or neetsfoot oil. Heat oil and beeswax in double boiler until wax is molten and blended with the oil. Use warm.

2. (from Scotland) a mixture of 50% Honey butter (whipped honey) and 50% anhydrous lanolin (de-hydrated lanolin). Mix and heat in double boiler as above. Use warm.

~ Some thoughts on treatment of dry-reeded pipes. Thanks to Mike MacHarg and Brian McCandless:

1. Oiling of wood serves to prevent cracking in two complimentary ways – inhibits excessive water uptake by the wood and inhibits moisture loss from the wood. If you live in a region where relative humidity changes by more than 20% in the course of a year, then oiling of the inside and outside of the drones will reduce the chance of cracking over a long period of time. Oiling of cylindrical bore chanters (such as Scottish and Northumbrian Smallpipes) noticeably improves the tone and prevents leaks at keypads. Beware, however, with conical bore chanters, for certain woods (especially the lighter fruitwoods) may absorb enough oil to significantly alter the bore dimensions, which can drastically affect intonation and pitch.

2. If you live in a climate zone typified by very dry winters (relative humidity less than 50%), then you may further help sustain your pipes’ wood moisture by leaving a humidifier in the pipe case and by packing the pipes away after each use. The easiest form of humidifier to make consists of a 2″ x 2″ (5 cm x 5 cm) sponge held inside a perforated zip-lock bag. periodically moisten the sponge with water. Initially, put one drop of chlorox on the center of the sponge as an anti-fungal agent to reduce mold growth on the sponge.

3. Try to avoid playing your pipes in extreme temperature conditions, especially extreme heat. Never leave your pipes exposed to the elements or to heating, air conditioning, or ventilation ducts. Aside from the obvious problems the reeds will give you, there is a significant risk of wood, glue, and finish damage.

38

BAGPIPE MAKERS

A list of bagpipe makers who specialize in the manufacture of Scottish smallpipes, Border pipes, and Northumbrian smallpipes.

– U.S.A.

Michael MacHarg, RFD2, Route 14 Box 286, South Royalton, Vermont

– GREAT BRITAIN

John Addison, The Poplars, Ings Lane, South Somercotes, Louth, Lines, LN11 7DA England

Jimmy Anderson, 90 Stirling Road, Larbert, FK5 4NF Scotland

Heriot and Allan, 28 Fairfield Green, West Monkseaton, Whitley Bay NE25 9SD England

Julian Goodacre, 29 Bellevue Road, Edinburgh, EH7 4DL Scotland

David and Hamish Moore, Upper Roshven, 3A Marine Parade, North Berwick, East Lothian Scotland

Colin Ross, England 5 Denebank, Monkseaton, Whitley Bay, NE25 9AE

Ray Sloan, Bywell, Northumberland England

PIPING SUPPLIES, MUSIC, ETC.

– U.S.A.

Highland Heritage, 131 East Main Street, Newark, DE 19711

Lark in the Morning, P.O. Box 1176, Mendocino, CA 95460

McIntosh Bagpipe Supplies, 933 Braddock Road, Pittsburgh, PA 15221

– GREAT BRITAIN

Chevy Chase, Cliffside, Rothbury, Northumberland, NE65 7YG England

39

REFERENCES

BOOKS

Anthony Baines, Bagpipes, pitt Rivers Museum, 1960.

W. A. Cocks and J. F. Bryan, The Northumbrian Bagpipes, Northumbrian Pipers’ society, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1975.

Francis Collinson, The Traditional and National Music of Scotland, Vanderbilt University Press, 1966.

Grattan Flood, The Story of the Bagpipe, Walter Scott Publishing Company, London, 1911.

Richard D. Leppert, Arcadia at Versailles, swets and Zeitlinger, Amsterdam, 1978.

W. L. Manson, The Highland Bagpipe, Paisley, 1913.

Francis O’Neill, Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Chicago, 1913.

Keith Proud and Richard Butler, The Poetry of the Pipes, Border Keep, Ltd., 1983.

Bruce Stokoe, Northumbrian Minstrelsy

TUTORIALS

A Tutor for the Cauld Wind Pipes, by Gordon Mooney

A Basic Tutor for the Northumbrian Smallpipes, by Richard Butler

(These tutors are available through Chevy Chase, listed page 39).

BAGPIPE ORGANIZATIONS

The Bagpipe Society, c/o David Van Doorn, Editor, 49 Osborne Road, Hornchurch, Essex, RM11 lEX England

College of Piping, 16-24 Otago Street, Glasgow, G12 8GH Scotland

The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society, c/o Jean Campbell, Secretary, 95 Avenue Park Street, Glasgow, G20 8LL Scotland.

The Northumbrian pipers’ Society, c/o Jack King, Secretary, 7 Valerian Avenue, Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland, NElS OEA.

Northumbrian Small Pipes Society of North America, 93 Rolph street, Tillsonburg, Ontario N4G 3Y2 Canada

United States Piping Foundation, 2614 Darby Drive, Wilmington, Delaware 19808 U.S.A.

40

–

——————————————-

——————————————-

An Invitation to participate in the

NORTH AMERICAN

ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND

AND BORDER PIPERS

The North American Association or Lowland and Border Pipers (NAALBP) was organized in late 1989 to foster interest in Scottish Lowland and Border pipes. For the most part, these are the bellows blown or “cauld wind pipes”. The association exists to network together players and enthusiasts who live in North America. The association publishes a bi-annual Journal and an annual membership list to facilitate the exchange or music, information, and experiences. Among the long-term goals or the organization are hosting an annual meeting, producing a cassette or North American players, and publishing a tunebook.

You are invited to participate in the NAALBP by returning the membership form and yearly dues. Membership in the NAALBP is open to all persons who are interested in the bagpipes or lowland Scotland and or the border regions encompassing northern England and Northumbria. The NAALBP welcomes your participation and invites you to submit articles, music, photographs, or other information you have written or collected.

Please send inquiries and Membership form with check for $15.00 payable to Brian E. McCandless [Editor’s note: NAALBP no longer exists, and therefore you cannot join]:

NAALBP

Brian E. McCandless

243 West Main Street

Elkton, MD 21921

Chairman: Alan Jones —– Coordinator: Brian McCandless —– Advisor: Mike MacNintch

(cut on dotted line)

—————————————————————————————-

NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

MEMBERSHIP FORM ———–

DATE:

NAME:

ADDRESS:

PHONE:

OTHER PHONE:

41

The JOURNAL of the North American Association of Lowland and Border Pipers (N.A.A.L.B.P) is published by the N.A.A.L.B.P. to provide information and music pertaining to the bellows blown pipes of Scotland and northern England to its members. The JOURNAL is edited by Brian McCandless and was typeset by Michele and Brian .McCandless. The N.A.A.L.B.P. is indebted to EIlen·Schubert of Wilmington, DeleIaware for layout and calligraphy of the logo. Additional copies of the JOURNAL may be purchased from the Editor for for $8.00 U S.

The JOURNAL of the N.A.A.L.B.P. welcomes any and all contributions pertaining to the bellows blown pipes of Scotland. Send in your tunes, notes articles, photographs, comments, suggestions, criticisms and letters to: NAALBP, c/o Brian E. McCandless, 243 W.Main·Street, Elkton, Maryland 21921.

Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy of names, places and events. The Editor regrets ·any errors and appreciates notification of correction, which will be duly noted in the following issue. Any photoduplication or other copying of this document is strictly forbidden. The Editor and Authors kindly request that permission be obtained for duplication of selected portions for educational purposes only.

The N.A.A.L.B.P. recognizes other existing ·organizations related to Bagpipes and welcomes their reciprocal interaction.

Pingback: North American Association of Lowland and Border Piping Journal 1990-94 Back in “Print” | Alternative Pipers of North America