To download the original journal as a scanned pdf please click here.

JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 4 JUNE 1992

CONTENTS

QUOTATION PAGE………………………………………………………………………….3

FROM THE EDITOR LETTERS………………………………………………………..4

F.Y.I…………………………………………………………………………………………………..9

BAGPIPES IN THE BOSTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS by Steve Bliven………. 16

SOME ANTIQUE SCOTTISH SMALL PIPES· by Alan Jones…………………………. 20

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONG PIPES· by Denis Brooks…………………………… 23

GEOGHEGAN’S TUNES…………………………………………………….. 28

LOWLAND PIPE NOMENCLATURE·by Ray Sloan………………………………….. 51

THE MANY SETTINGS OF MAGGIE LAUDER· by Brian E. McCandless……….. 55

PROFILE·- GORDON MOONEY……………………………………………….. 58

DISCOGRAPHY – by Mike MacNintch………………………………………… 60

REVIEWS:

HAMISH MOORE LOWLAND PIPE WORKSHOP, 1991 by Steve Bliven…….62

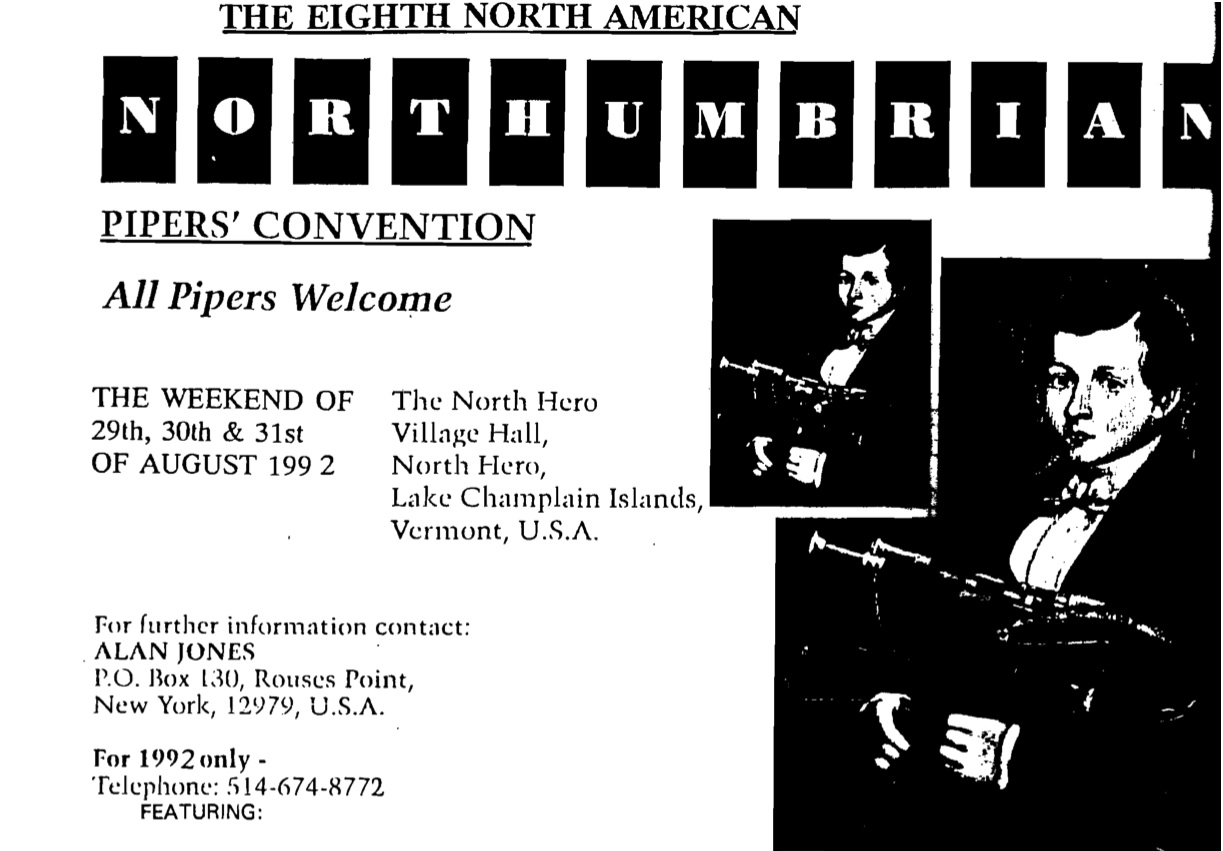

NORTH HERO PIPERS CONVENTION, 1991 by Alan Jones……………….64

PIPER’S COLLOGUE IN SCOTLAND, 1991 by Alan Jones………………………. 66

PIPER: A COMPUTER PROGRAM FOR PIPE MUSIC – by Steve Bliven……….. 72

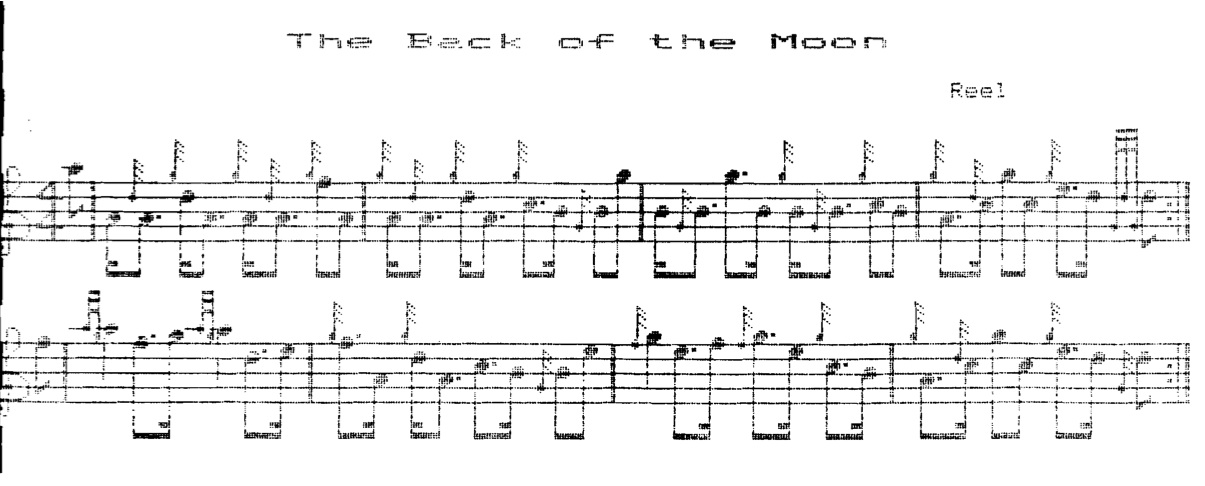

CALL FOR YER PIPERSTHREE·by Michele McCandless…………………………. 74

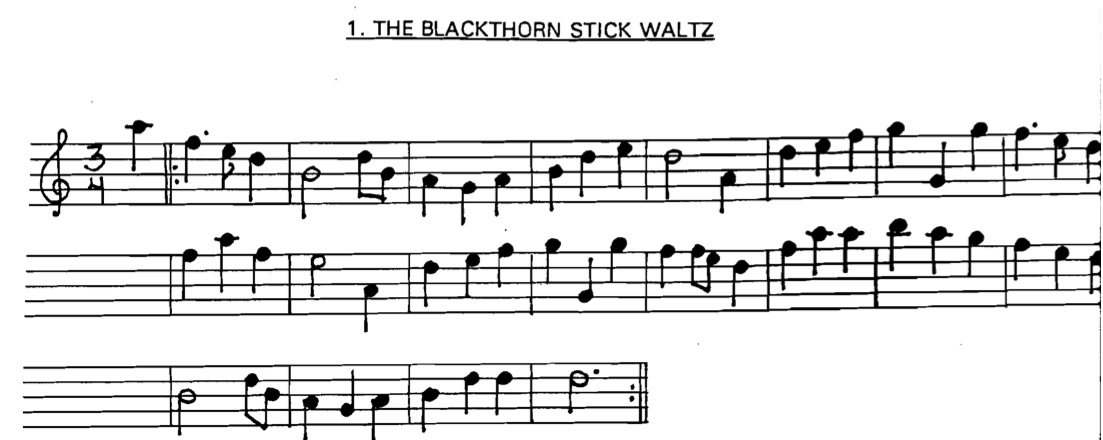

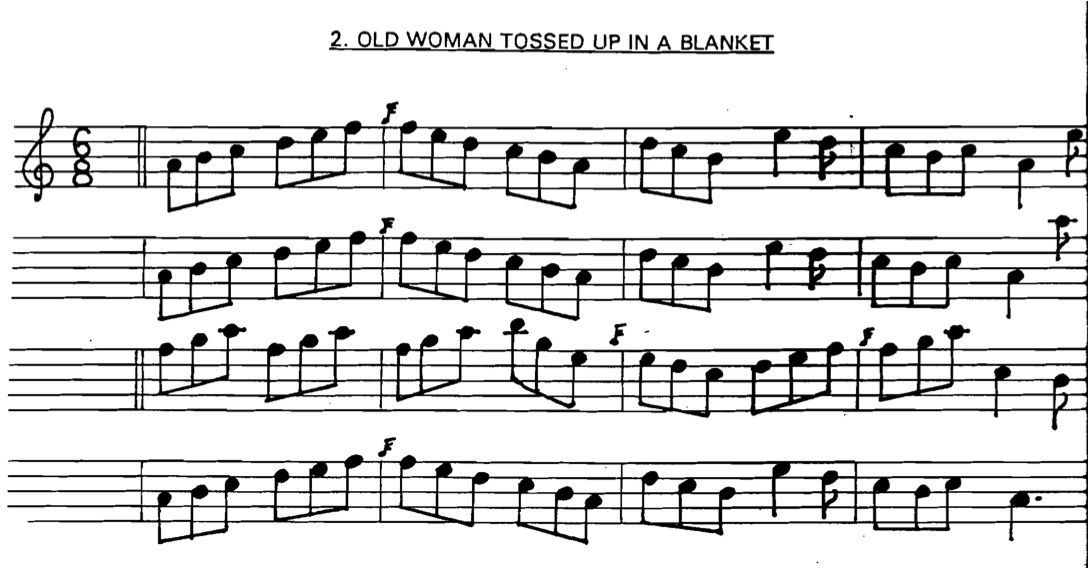

TUNES FOR LOWLAND PIPES, SMALLPIPES, AND PASTORAL PIPES……… 75

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS………………………………………………………. 81

LIST OF PIPE MAKERS………………………………………………………………….. 83

1

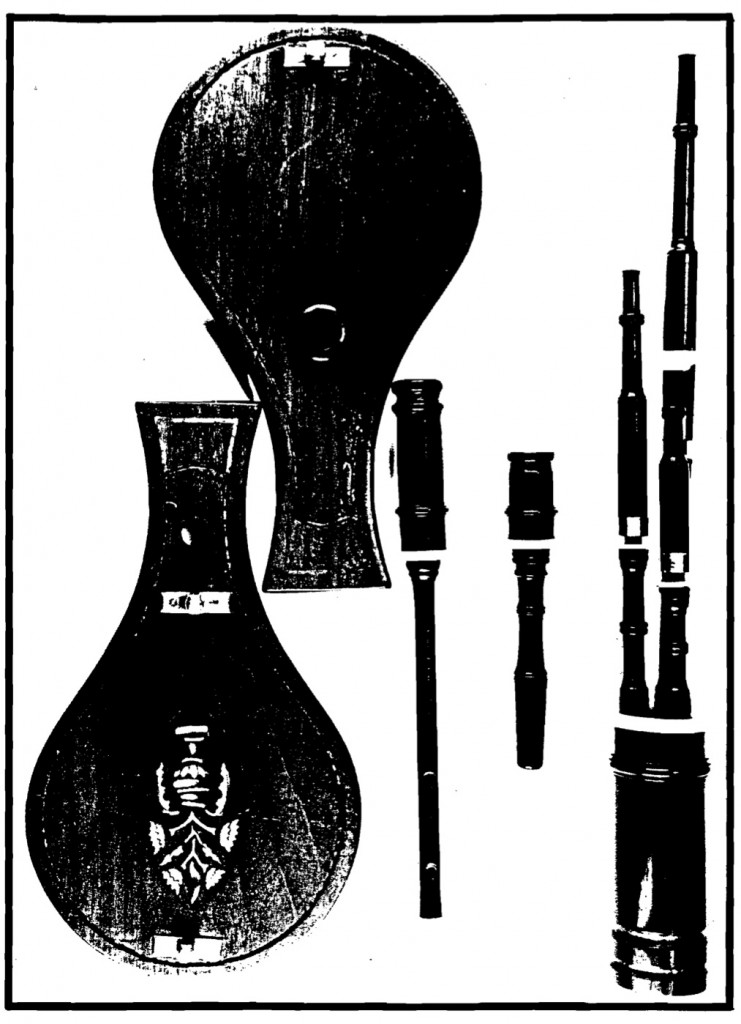

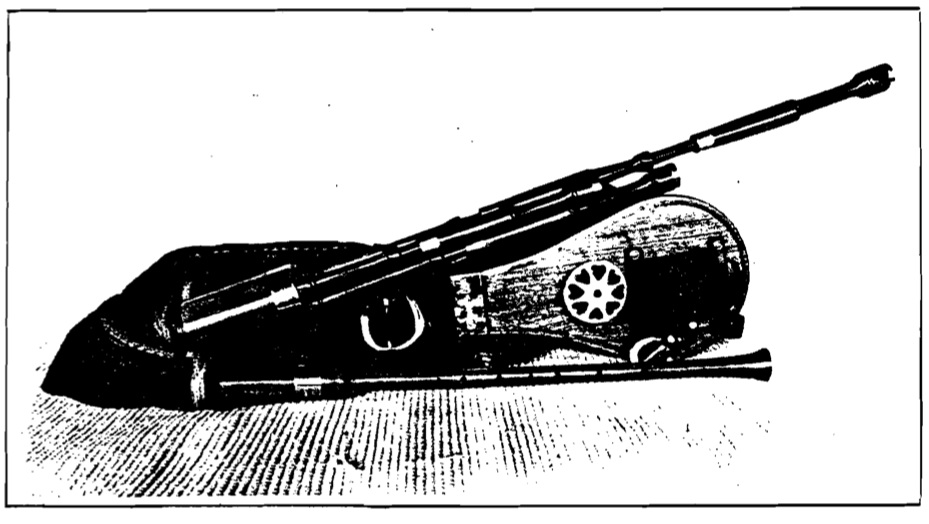

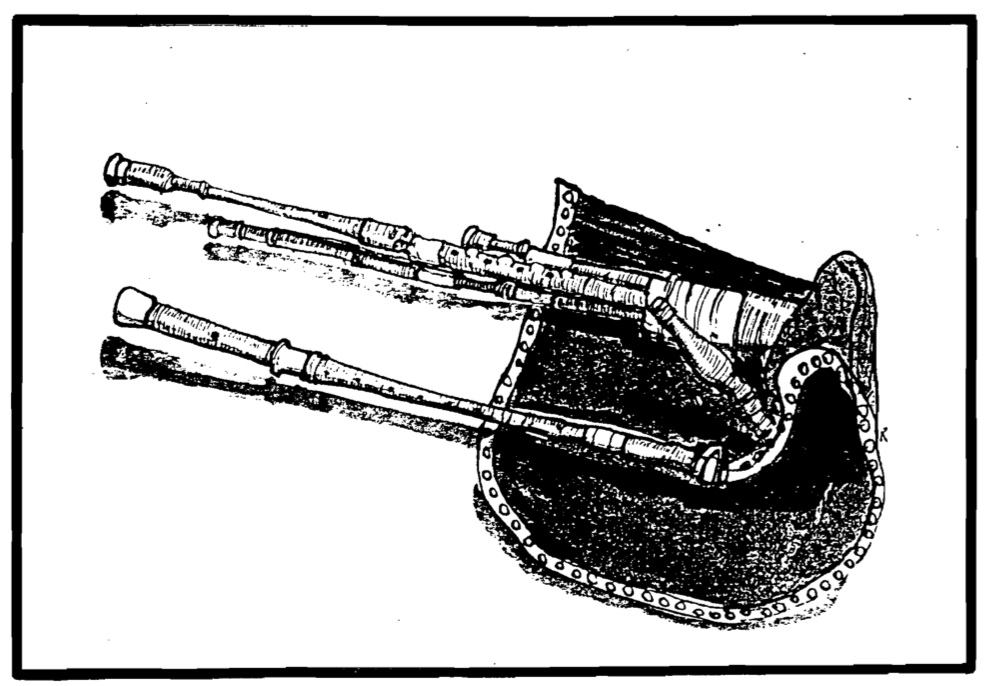

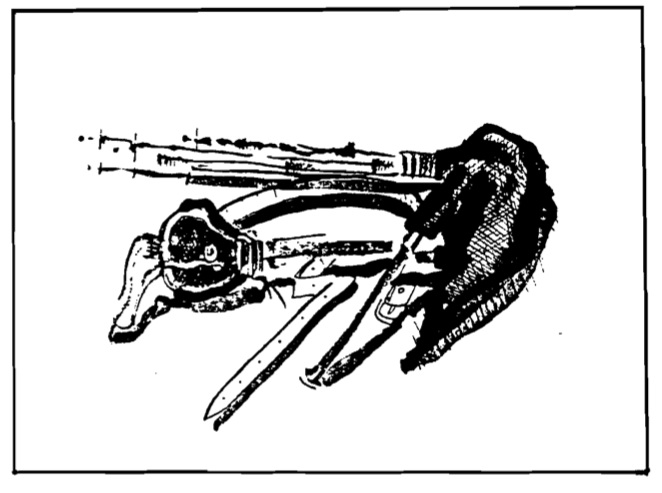

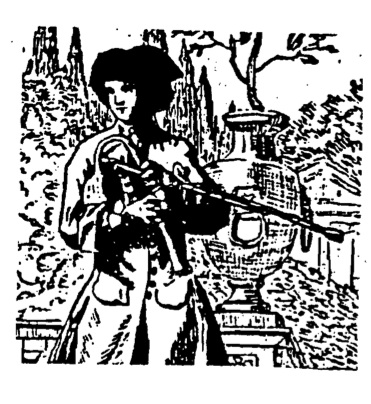

Early 191h century Scottish smallpipe bellows and pipe components belonging to Alan Jones. For full story see page 20.

2

QUOTATION PAGE

“The drone is mightier than the sword.”

– From John Hodian, jazz composer:

“Talking about music is like dancing about architecture.”

– From Gordon Mooney:

“The bagpipe is the missing link between music and noise.”

“If when asked to design a horse the Committee came up with a camel, what was their design brief when they came up with the bagpipes?”

“When asked why the bagpipe had drones, the old piper replied, ‘Well without the drones you might as well play the piano.”’

– From Julian Goodacre:

“Reeds are like your thoughts – you only really ever get to know your own.”

“A bagpiper is a beast blowing into the skin of another beast.”

– From The Insane Art of Reed Making, by Patrick Sky:

“Reed making is a madness similar to that gained by gazing deeply into the head of a good pint of Guiness. Many old and ancient curses and poetry have been composed whilst shaving a reed.”

– From Woodwind Instruments and Their History, by Anthony Baines, 1967:

The Scottish Lowland Pipe is no longer regularly played. There are two forms, both with bellows, and with three drones in a common stock. The ordinary form has a chanter like that of a Highland pipe, but with narrower conical bore. Its drones are tuned in the Highland way, a, a, A. The miniature form has a short cylindrical chanter (though it may be tapered on the outside), and this, unlike the cylindrical chanter of the Northumbrian small-pipe, is open-ended and fingered in the ordinary way. Thanks to this bore, the Highland pitch and scale are obtained with a shorter chanter, and there has been talk of a revival of the Scottish miniature pipe in the form of a mouth-blown pipe with two or three separate drones, for young persons whose hands are too small to manage the full-sized Highland chanter.”

– From Syntagma Musicum, by Michael Praetorius, ca. 1615:

“Then there is a small bagpipe or Hummelchen which has been imported from France, in which the wind is produced solely by a small arm-operated bellows. One whom we mentioned earlier had the remarkable idea of making a whole consort of five bellows-operated bagpipes like these, for playing music in four or five parts. I must confess, however, that their overall effect does not strike me as particularly pleasant.”

– Last: “If you hear bagpipes, then the bears must be coming…….The Bears”

3

FROM THE EDITOR

At the turn of the year, the Committee of the N.A.A.L.B.P. (pictured below) held a meeting at the home of Brian McCandless, your Editor. As Alan Jones, our Chairperson, brought in his bagpipe collection out of the frosty night air, we (Mike MacNintch, Tom Childs, and Brian and Michele McCandless) gawked. After a couple of days of piping, we sat down and discussed the Journal and the N.A.A.L.B.P.. The outcome of it all was two-fold: One) by Constitution we need to hold elections for the posts of Chairperson, Advisers, and Editor and Two) we ought to set some future goals. Naturally, we had many ideas, and we would like to share them with you now. Enclosed with this issue is a questionnaire soliciting nominations for Chairperson, Advisers, and Editor. The function of the Chairperson is to serve as a visible and accessible liaison from our members to the piping community at large. In this capacity, Alan Jones has served us well, with his numerous connections in England and Scotland, and with the benefit of his traveling collection which seems to grow like kudzu on a telegraph pole. Our Adviser, Mike MacNintch, has been extraordinarily enthusiastic about promoting bellows piping, the N.A.A.L.B.P., and helping Michele and me get the Journal together each time. And there’s myself – Mr. Journal. Here we are at Issue 4, having learned a lot, but barely scratching the surface. There is so much that we don’t publish – one night’s phone call to Sam Grier, for example, could occupy an entire issue! We wanted to do an article on Scottish settlement of North America and on physics of chanters and drones, but the amount of information – staggering! My personal bias towards Pastoral pipes leaps forth from each issue, and I feel that Scottish smallpipes have been somehow neglected. It is time for me to transfer this privilege along to another member willing to throw their heart and soul into it. Personally, I would like to devote my time to my professional science and semi-professional musical careers, piping research, pipe playing, instrument making, and maintaining my wonderful hundred-year old home. So far the Journal has been a wonderful experience and I am proud of the high quality we have maintained, and now it is time to turn over the reins. As members of the N.A.A.L.B.P., take stock of your own situation and what you might contribute to this organization as a Committee member.

So what we, the ‘executive committee,’ hope is that you are moved enough by our plea to nominate yourself or another willing and able person for the posts available. After the nominations and questionnaires are received we’ll hold elections by mail through the fall of 1992. With luck, a new Committee will exist by January 1993 and Issue 6 of the Journal will be underway. About those future goals, we envision: 1) a cassette of our members playing their instrument of choice; 2) a gathering of Lowland pipers; 3) a tutorial book and tune book for Scottish smallpipes. We invite your further ideas towards future ventures as an Association, especially towards getting together soon! Thank you for your support and for the articles, photographs, tunes, and comments. Stay tuned for Issue 5 – it will be an autobiography of the Association based on the Questionnaires·returned and will serve to define the nature and level of playing on this continent at this moment in time. Don’t hesitate to write or call: Brian McCandless.

4

LETTERS

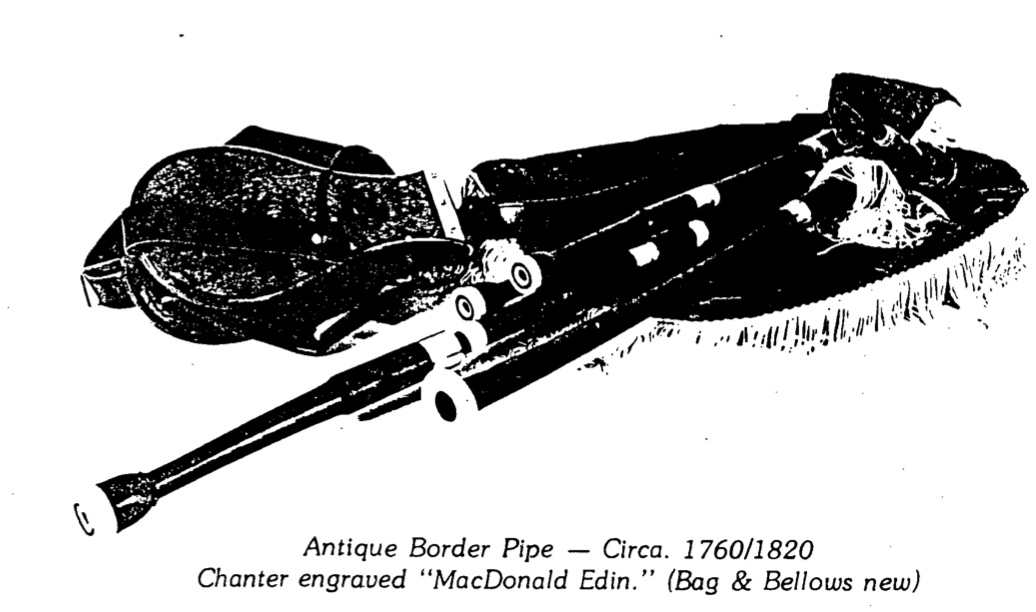

CONCERNING BORDER PIPES

Alan Jones, a well-known figure in our midst, has just added a set of Jon Swayne’s Half-long Border Pipes in ‘G’ to his impressive collection. On a recent visit to our editor’s home in Maryland, I saw and played this exquisite set. It is truly one of the finest sets I’ve ever seen or played, and despite the opinions of others that these are not ‘true’ historical Border pipes, they are an instrument worthy of inclusion into the Lowland arsenal. The particular set in question is of blackwood, mounted in imitation ivory and nickel silver. They are bellows blown, have four drones, and have a chanter which overblows reliably up to the twelfth.

As the photograph below shows, the outward appearance of this instrument is instantly recognizable as belonging to the Lowland and Border pipe family. The picture shows the Swayne set (center) flanked by two Border Pipes by John Addison (left) and two antique Border pipes (right). In addition to overblowing, the chanter has a rear thumbhole for fingering a flattened third, and in fact it resembles the French Bechonnet Musette-style chanter. The fantastic quality of these pipes is that they sound perfectly appropriate for playing music of Northumberland, the Lowland and the Borders, and France!

Bagpipes throughout history have developed according to the needs of the people who played them. Their development was molded by such influences as raw materials, musical taste, and regional popularity. While this pipe may not enjoy the historical prestige lauded upon the Union pipe, it fulfills a role today, and the maker has chosen to name it as a Border pipe. If you have a hard time accepting that, you may think of it as a sort of Pastoral pipe. The sound of the sets available in low D certainly must be comparable in some degree-to the Pastoral pipe.

Such a versatile instrument should not be overlooked. It is interesting to note that a few different fingering systems work well on these pipes, and they overblow easier than do many of the Uillean pipes I’ve played. If you are at all curious about this instrument, you may consider listening to the music of Blowzabella (recent albums) or, better yet, write to Jon Swayne [see makers list]. I think we do well to keep an open mind to modern innovation and change regarding the instruments within our musical idiom. There are several other bellows blown pipes by other makers that also deserve recognition, such as the Leistershire smallpipes by Julian Goodacre and the open-ended keyed shuttlepipe by Dave Shaw.

Mike MacNintch

The table at our Editor’s house, littered

with Border pipes. From the left, 1) John Addison pipe in A; 2) John Addison Half-long in A; 3) Jon Swayne pipe in G; 4) antique Border pipe [see Journal #2, p. , 10; and 5) antique Border pipe [see Journal #2 p. 7]. Photograph by Brian McCandless.

5

LETTERS (CONTINUED)

A REQUEST

Dear- Colleague:

I’m collecting any information about the tale of “The Musician (very often playing the bagpipes) who escapes Wolves thanks to his Instrument”. So I’d very much appreciate receiving variants (ancient or not), bibliographical resources, remarks, commentaries.

Many Thanks, J.-L. LE QUELLEC

HAMISH CLASSES 1992

Dear NAALBP:

I would be grateful if you would publish this announcement in the next issue. THE 2ND ANNUAL HAMISH MOORE SCHOOL OF CAULD WIND PIPES will be held in Valle Crucis, North Carolina, July 26 to July 31, 1992. There will be a limited number of pipes for hire. The following topics will be covered: bellows technique; playing techniques; Border and Lowland repertoire; harmony and part playing; pipe maintenance; and reed making. For early reservations and further information, please contact:

Jo Johnston, Virginia

Dear Mr. McCandless:

Did you know that Hamish Moore will be conducting a school in California this summer? Dates are August 2 through 7, at the Oak Hill Ranch, Santa Rosa. Interested pipers can contact John Creagor for more information.

Many Thanks,

John Dally, Washington

6

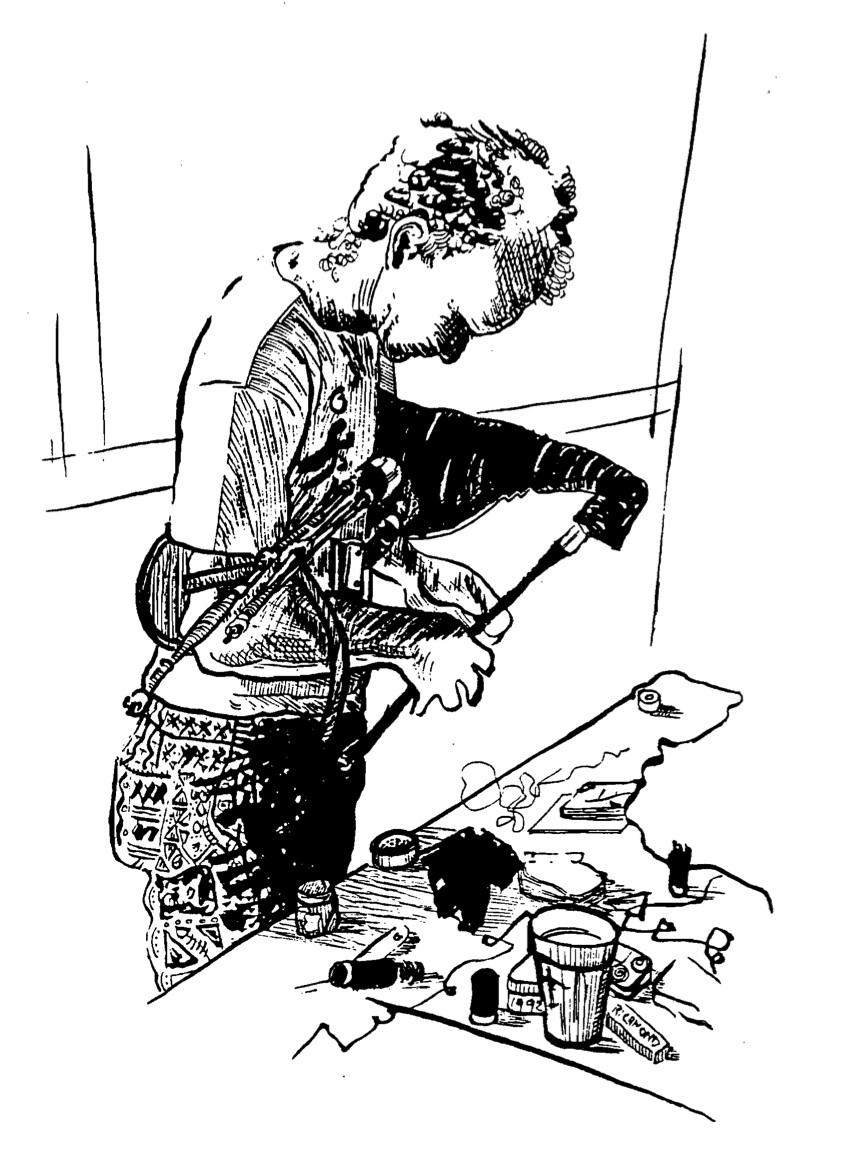

Hamish Moore at his table at the 1991 Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention at North Hero, Vermont. Sketch by W. Richmond Johnston.

7

LETTERS (CONTINUED)

FROM THE LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS’ SOCIETY

Dear Brian:

I am writing as a committee member of the lowland and Border Pipers’ Society. At our last committee meeting we agreed to contact the North American Association of lowland and Border Pipers to establish formal links between our Societies. We are aware that over the past few years we may have appeared to be rather unresponsive to requests from over the water. This hasn’t been meant in an unfriendly way, it is just that The Society has in the past few years been run by very few active members all of whom have demanding family and business commitments. Over the last couple of years we have however pulled together a larger working committee and now we are seeing the results.

Last year’s Collogue in Jedburgh was so successful that we are organizing another this August 29th. This time it will be in Peebles. We have nearly completed an informal tape for distribution to our members. This year’s piping competition had for the first time an International section with entries on cassette. Next year you should all take part in this! It always is held at Easter so you all have plenty of time to practice!! Our new Editor of Common Stock is Jock Agnew. He plans his second issue for this summer. Finally, we are currently having Gordon Mooney’s Tutor for the Cauld Wind Pipes reprinted.

If you agree to establishing this link then we will put you on our mailing list and you could put Jock Agnew on yours. Thus your Journal and Common Stock could review each others’s issues.

We look forward to hearing from you soon.

Yours Aye,

Julian Goodacre, Peebles, Scotland

REQUEST FOR OLD TUNES AND PIPING REFERENCES

Dear Sir:

I am writing to enquire if you have any pipe tunes you could send me. I have been a collector of tunes for many years. Since I retired I have managed to make up a book of tunes of pipers past and present of the County of Clackmannanshire and have lodged copies at the local library and the Scottish Museum in Edinburgh. Do you have any old Magazines of piping that I could have? I have had over 50 years in Piping and Drumming. I taught the school pipe band for the last 13 years, until I retired, and I do miss it all. Do you have any electronic pipes made in your part of the world? I am looking for ideas that I may use to pass the time…

I have various copies of books I could send you, if interested, such as the Mannan Pipes, something like the Small Pipes made in our county, in the 1940’s. I made a book up of the plans and photocopied it.

Robert S. S. Gray, Clackmannanshire, Scotland

8

F.Y.I.

Reproduction of the “Montgomery” Scottish Smallpipe

Julian Goodacre, pipemaker from Peebles, Scotland, sent us this photograph of a reproduction he made of an 18th century Scottish smallpipe residing in the collection of the Scottish United Services Museum in the National Museums of Scotland. The original pipes are truly noteworthy for they bear the following inscription on the ivory drone ring: “HONL. COLL. MONTGOMERY 1ST HIGHLAND BATTN. JANY. 4 1757”. The pipes were the subject of a detailed article by Hugh Cheape, curator at the museum, in the Vol. 4, No. 1 issue of Common Stock, Journal of the lowland and Border Pipers’ Society, 1989. Mr. Cheape hails the set as the “Rosetta Stone” of Scottish bagpipe musicology! Julian measured the set and made this reproduction, which was brought by Gordon Mooney to the Seventh Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention held at North Hero, Vermont in August 1991 [see review by Alan Jones]. Some of our readers attended the workshops held by Gordon where he demonstrated the set.

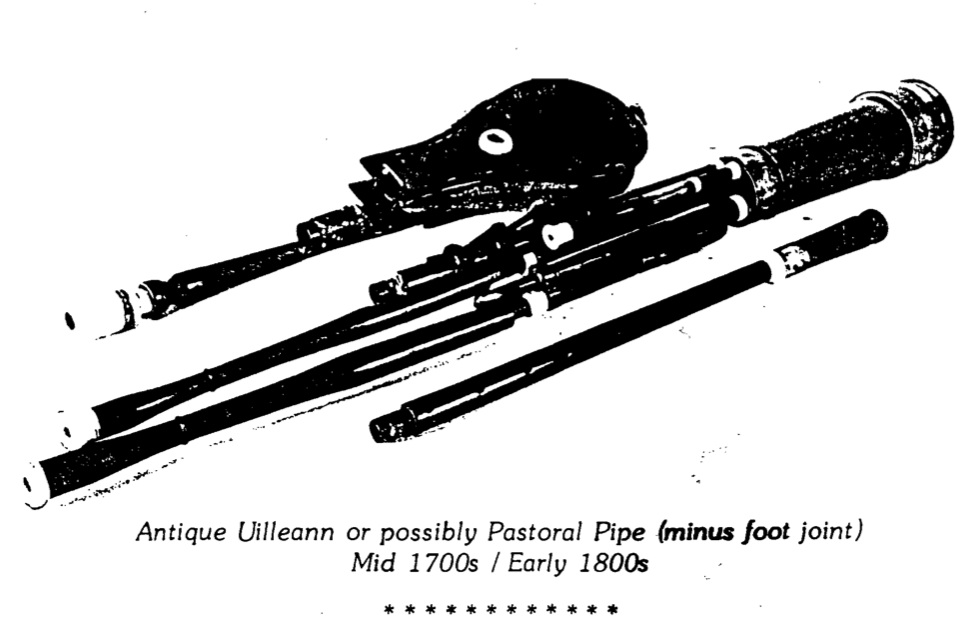

Pastoral Pipes Described in Recent Article

The Bagpipe Society has recently released its 6th issue of Chanter which contains an article by Steafan Hannigan entitled “Where did the Irish Pipes come from?” The very authoritative article contains a wealth of information on the history of the Uillean bagpipes, with a section devoted to the Pastoral pipes. He suggests that the Irish pipes were an adaptation of the Scottish Pastoral pipe.

The Bagpipe Society also recently published Newsletter 22 which contains myriads of lowland piping tidbits. To join the Society, please write to Val Woollard, Membership Secretary, Essex, England.

9

F.Y.I. (CONTINUED)

A Hybrid Smallpipe

In recent months, Mike MacHarg and Brian McCandless each have constructed smallpipe versions of the “Reel pipe” described by Sam Grier in Issue 2 of the Journal, page 12. In the photograph below, of a set in “D” made by Brian, you can see that the pipes have a second chanter, turned on the outside to a drone aesthetic and mounted parallel to the drones. In use, all the holes but the one needed are closed by beeswax plugs. The drones are tuned to the tonic (D) and the second chanter or regulator is configured to play a harmony note of the desired key. For example, to play Keelman O’er the Land, the hole giving “A” is opened. The sound is very robust and the regulator volume is close to that of the chanter, as one finds with the French Musette du Cour. For this reason, the regulator holes are drilled smaller than one would use on the chanter, and the chanter end is plugged. Both of these steps reduce the regulator volume to a pleasing harmonic blend. The regulator was tuned by setting the reed so that the bottom holes were in tune with the chanter and then up-cutting or filling the upper holes to bring them into tune. This technique is the same as used by Uillean pipe makers to adjust their regulators, the logic being that the upper holes are more sensitive to position than the bottom holes. A little creativity applied to a drone switch and a plug-and-chain system would increase the versatility of the instrument in use.

Smallpipe in D by Brian McCandless based on the “Reel Pipe” described by Sam Grier in Journal 2, page 12. The chanter is of ebony, mounted with ivory, and the drones are of ebony, with brass tuning slides and mounted with black walnut.

Components of the “Bionic Small Pipe” made by Michael MacHarg for his son, lain. In addition to having a chanter-regulator, the instrument has seven chanters and six drones, spanning the musical keys of A, B-flat, C, and D (Scottish smallpipe); A and B-flat (Border pipe); and D (Northumbrian)!

10

F.Y.I. (CONTINUED)

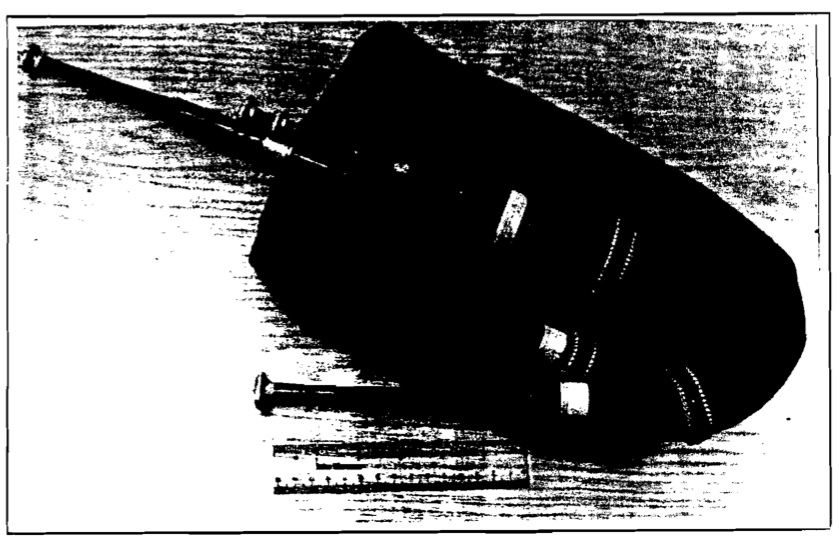

1970’s Recording and Photograph of Pastoral Pipe

As you may notice in the Discography of this issue, the Pastoral bagpipe appeared on a recording by the California based Westwind International Folk Ensemble in 1975. The booklet which accompanied the album, Dances of Europe, gave the following brief description and this photograph of the instrument. The ivory instrument in the photograph is reminiscent of the Pastoral pipe shown in the color supplement of Journal 3 which belonged to Bob Thomas and which was subsequently destroyed in a house fire. The recording is of the English dance tune, the Dorset Reel (or Dorset Four Hand Reel).

” ‘The Lowland or Border bagpipe seems to have gone out of use about the middle of the last century’ (from The Traditional and National Music of Scotland by Francis Collinson, 1966). On this recording is the only known operating pipe of its type. It is a form of hybrid Irish Union Pipe which neither Ireland nor Scotland will claim as their own. It must in true fact be English! ‘The chanter is like that found on the Irish pipe, but it has an added foot joint and is played as the ordinary Scots form’ (ibid.). Jamie Allen was a well known performer on the instrument. (A piper who became a legend of the Border counties of England.)”

Antique ivory Pastoral bagpipe featured on the Westwind International recording, Volume I, 1975.

Pastoral Bagpipe Discovered in Cecil County. Maryland

A late night phone call from Alan Jones a few months ago has kept your Editor busy tracking the story of a Pastoral bagpipe which came to Cecil County, Maryland around 1790. The pipe was made by William Squire in the mid 1700’s in Buchlyvie, Scotland and was passed down through the Squire family for all these years. The pipes are in the possession of Mr. Richard D. MacKie and are shown on the next page on Mr. MacKie’s dining room table. The full story of this rare set shall be the subject of a future article, but suffice to say for now that your Editor has taken a most serious interest in this instrument and has taken full measurements and has nearly completed duplicating the set. They are made of a moderate density wood such as cherry, and have three drones. The original chanter reed (broken) and one drone reed are still with the set. Using an Uillean pipe reed, the chanter was “played” briefly for a tape recorder, revealing its pitch at somewhere between D and E-flat. Sam Grier has kindly fabricated several chanter reeds based on measurements of the original and they play well in both his John Addison Pastoral pipe and in the McCandless reproduction of the Squire chanter, giving pitches from C# to near E-flat. More to come on this Colonial era Scottish-American connection!

11

F.Y.I. (CONTINUED)

Richard MacKie. of Cecil County. Maryland and his Pastoral Pipe by William Squire (c.17601.

Raw materials and reproduction of Squire Pastoral pipe chanter and drones by Brian McCandless.

12

F.Y.1. (CONTINUED)

Pipemaker in Maine

One of our members, Michael A. Dow, a woodworker and carver from York, Maine has been busy this winter, and completed construction of smallpipes in B-flat. He has been experimenting with a variety of woods and reports success with greenheart wood, apple, and blackwood. Below are two photographs, the greenheart set (shown without bellows) and the apple set (shown with bellows). The bellows valve guard and the chanter soles are made of moose antler which he says is harvested from the forest floor, as the Moose apparently drop their antlers each year.

Two Scottish smallpipes in B-flat made by Michael Dow.

13

F.Y.1. (CONTINUED)

Large Bellows Discovered

While roaming the Connecticut River Valley in search of scenery and bagpipes, Mike MacNintch and Brian McCandless came across the ideal bellows for a group of smallpipers. Mounted vertically, it takes two to pump and requires a distribution manifold for optimal pressurization.

14

F.Y.1. (CONTINUED)

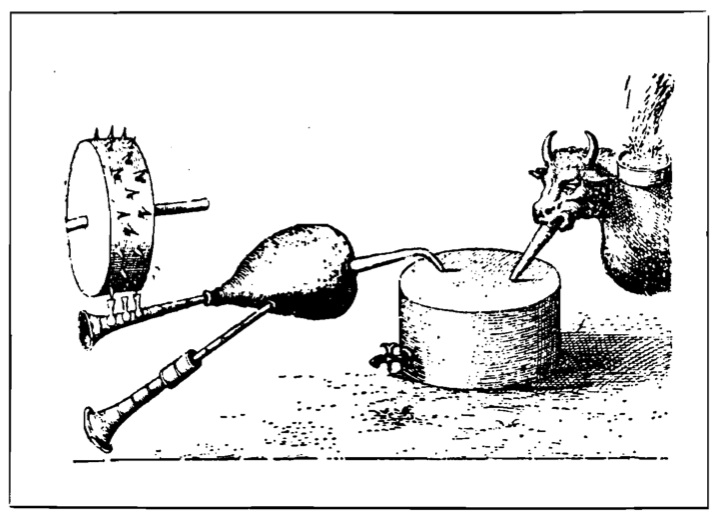

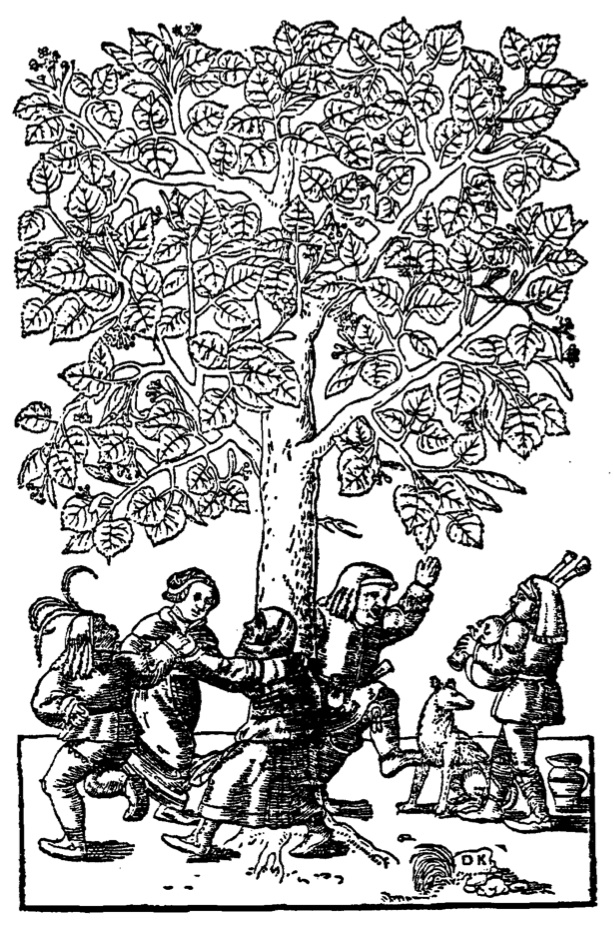

In a similar vein, the following print appeared in The Galpin Society Journal, Number 26, May 1973, page 8, and reproduces an illustration from Robert Fludd’s 1618 volume of Utriusaue Cosmi Maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, Physica atgue Technica Historia (‘Metaphysical, physical and technical history of both the. greater and lesser cosmos’).

BACK ISSUES OF THE JOURNAL

At this time, we have no more back issues of Journal #1 or #2 and only a few of #3. We do plan to reprint the back issues, but not for a few months.

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR MEMBERS

If you are a current member of the N.A.A.L.B.P., you will find a questionnaire inserted into this issue of the Journal. The purpose of this questionnaire is to provide information as the basis for a “Biographical Issue #5”. Issue #5 will feature short biographies of our members for the mutual benefit of all concerned. For example, it would be useful to know who else among us is learning the art of pipemaking and what techniques (say, historical versus modern) are being employed. The tentative format for the issue will be the members’ name followed by his/her address and a short list of the instruments played, repertoire, and other related interests. Please help us to expedite Issue #5 by returning the questionnaire by August 1, 1992.

15

BAGPIPES IN THE BOSTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS by Steve Bliven

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts houses a small, but representative collection of bagpipes. Incorporated within the Leslie Lindsey Mason Collection of Musical Instruments, they were originally gathered by Francis W. Galpin in the early to mid-1800’s (no instruments are post 1850). In the early part of this century the collection was acquired by William Lindsey of Boston and donated to the Fine Arts Museum in memory of his daughter lost during her honeymoon in the sinking of the Lusitania.

The entire collection, including bagpipes, was described in detail in 1941 by Nicholas Bessaraboff’. Along with the descriptions, Bessaraboff provides the following philosophic discourse regarding the sound of the pipes:

“The music of the bagpipes, especially that of the Scotch Highland bagpipe, affects the emotions strongly. It is passionately loved by many and disliked just as intensely by others. The perpetual pedal of the drones induces a philosophical calm in lovers of the bagpipe and completely unnerves the haters. Paradoxically, the chanters in this dialectical entity, so prosaically called the bagpipe, supply the excitement of change. Perhaps this strident antithetic juxtaposition of such contrasting elements may provide a clue to the violent emotional reactions to bagpipe music. “

Within the described collection are the following:

Mouth Blown

- Great Highland Pipes (Scotland, early 19th century)

- Cornemuse (France, ca. 1750)

- Biniou (Brittany, 19th century)

- Zampogna (Italy, early 19th century)

Bellows Blown

- Musette (France, ca. 1750)

- Uilleann bagpipe (Ireland, early 19th century)

- Lowland bagpipe (Scotland, 19th century)

- Northumbrian bagpipes (England, 19th century)

No additional pipes have been added to the collection since Bessaraboff’s work in 1941 indeed it does not appear that any have been added since the initial collection in the mid -1800’s.

Only the Uilleann pipes were on display, but a call to the curators, Sam Quigley and his assistant Darcy Kuronen, led to an invitation to investigate any of the instruments. On two visits to the museum, one including Tom Childs, these two gentlemen – particularly Mr. Kuronen – spent considerable time and attention in discussing the collection, allowing us to (gently) handle and closely examine the instruments. None are currently playable and most show the ravages of time, but it is obvious that steps have been taken to stabilize their condition and preserve them in their current state. (The Uilleann pipes and the musette have had some cosmetic restoration for display purposes.) I will limit further discussion here to the Lowland and Northumbrian pipes.

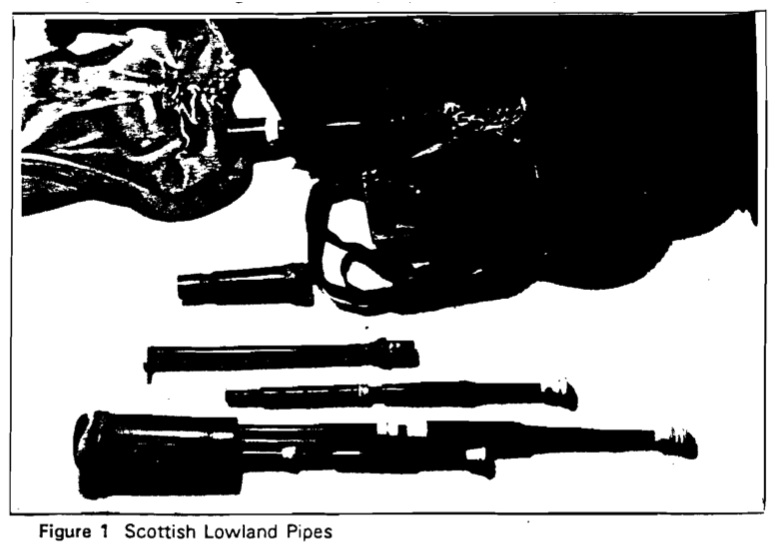

Lowland Pipes

A photograph of this instrument from Bessaraboff was published in this Journal in the August 1991 issue (page 8). It consists of the typical chanter and three drones in a common stock. Using a plastic reed and a Seiko chromatic tuner, we noted that the chanter was pitched in E (in fact it was dead-on E of the A-440 scale.) The drones are arranged in the tenor-baritone-bass configuration and are decorated with silver ferrules and ivory mounts. No reeds are present. Measurements of the chanter and drones are provided in Bessaraboff.

16

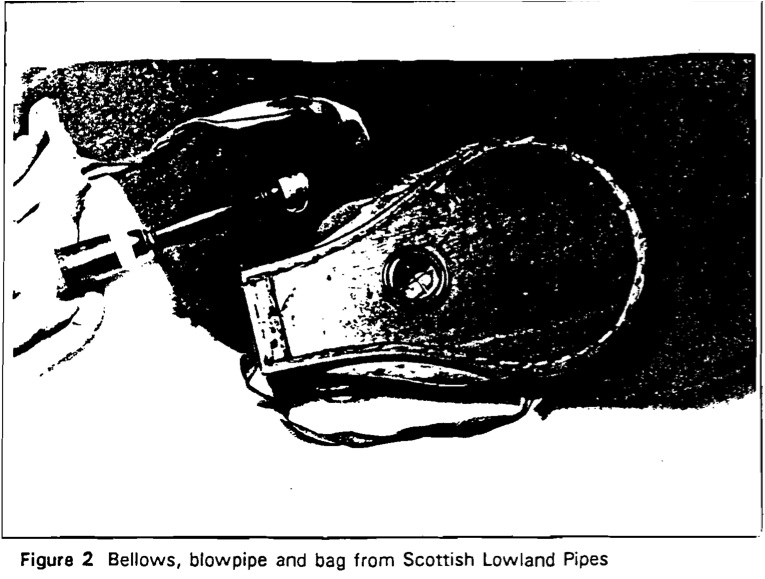

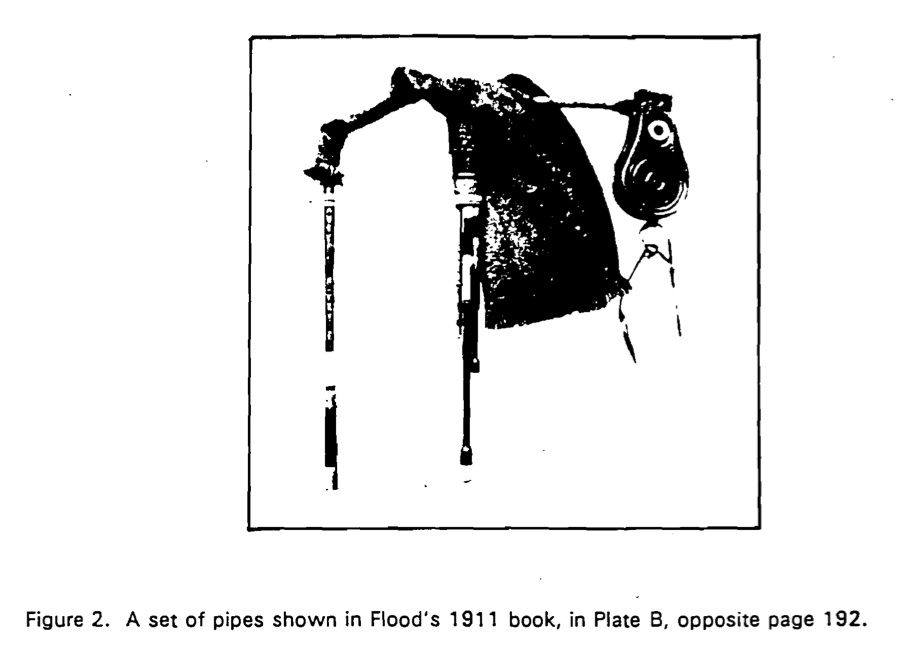

The bag has deteriorated and stiffened; the stock has torn away from the bag as may be noted in Figure 1. A dark green wool bag cover is included, devoid of decoration except for a fringing of the selvage at the openings. The bellows seem to be made of some sort of fruit wood (Figure 2). There is a metal bracket to hold the waist strap; a piece of ribbon is attached there, but it is not clear that it was original. The means of attachment to the elbow is not apparent. The leather of the bellows has also stiffened.

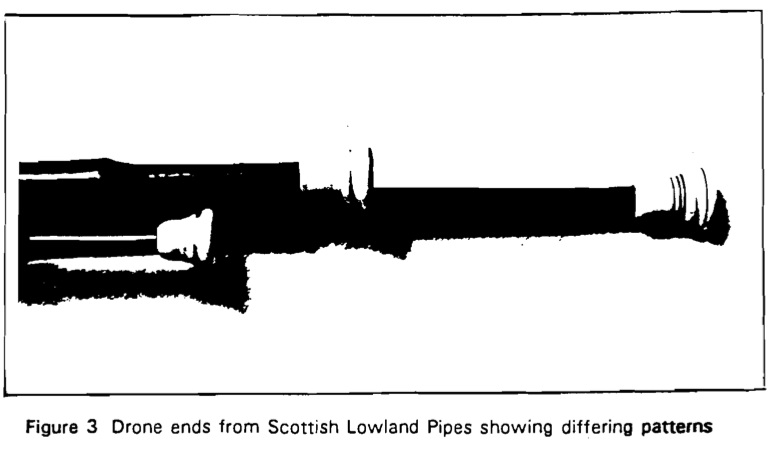

Figure 1 Scottish Lowland Pipes

The entire set is quite simple in design. The chanter has little in the way of decoration. The drones are interesting in that they seem to come from various sources. Figure 3 shows the variation in design of the ivory bells; similarly the sections of the drones differ in design and detail. The base drone features combing, there is a pattern turned into the lower section of the baritone.The mounts differ on all three lower sections and the upper sections of the tenor and baritone have silver ferrules while the base has an ivory ferrule. Unfortunately, over time several of the drone segments have developed splits. There are no historical notes to indicate the circumstances under which Galpin collected the pipes so it is unclear whether they were played in the “mismatched” condition or there was some attempt to complete the set after collection. It is tempting, however, to imagine this simple set of mismatched pipes being played by an itinerant piper for local dances in some rural village over 150 years ago.

Figure 2 Bellows, blowpipe and bag from Scottish Lowland Pipes

17

Figure 3 Drone ends from Scottish Lowland Pipes showing differing patterns

Figure 3 Drone ends from Scottish Lowland Pipes showing differing patterns

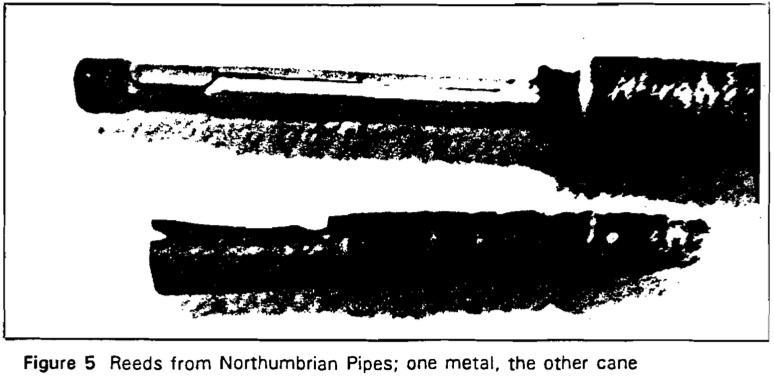

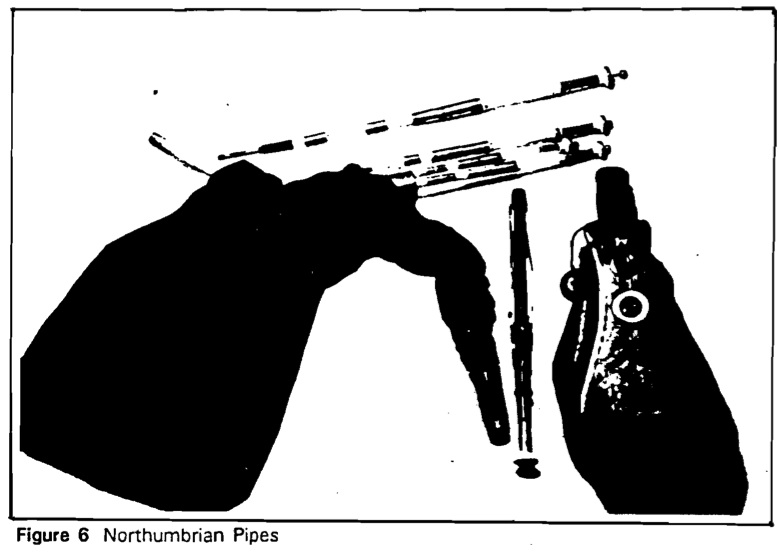

Northumbrian Pipes

This is an elegant set. It consists of silver and ivory drones with an ebony chanter bearing the inscription “?. Reid”. Bessaraboff tentatively identified the first initial as “C” but it seems more probable that the maker was either Robert (who used either “R. Reid” or “Reid”) or James, his son (who used either “J. Reid;’ or “Reid”) 2. As mentioned above, all instruments in the collection were assembled prior to 1850. Robert Reid died in 1837, James was 37 in 1850 so the

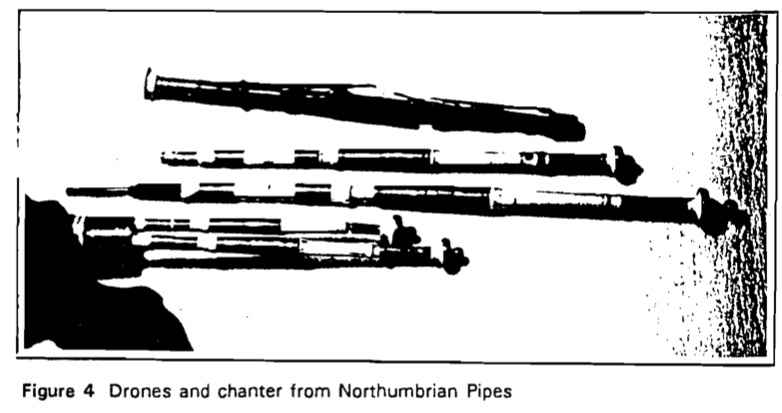

Figure 4 Drones and chanter from Northumbrian Pipes

Figure 4 Drones and chanter from Northumbrian Pipes

comparative dates provide no clue as to who the maker might be. Figure 4 shows the drones and chanter. The latter has seven keys, made from silver. The chanter sole is ivory with a silver band immediately above. Reeds are present in two of the drones (Figure 5); one is cane, the other is metal. Tuning beads are present in all four drones. This set also has some cracking and one of the drones has broken at the attachment to the

Figure 5 Reeds from Northumbrian Pipes; one metal, the other cane

Figure 5 Reeds from Northumbrian Pipes; one metal, the other cane

18

stock. As with the lowland pipes, measurements are provided in Bessaraboff.

The bag and bellows leather has stiffened but is intact. The bag cover is made of blue velvet and undecorated; there is no note as to whether the bag is original to the pipes or added at some later date, but it looks remarkably fresh. The blowpipe is ivory, the chanter stock appears to be ebony with a silver ferrule.

For additional details about these and other pipes in the collection consult Bessaraboff. For further information contact the Curator of Musical Instruments, Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave., Boston, MA 02115 (617)-267-9300.

In order to assist the Museum with their identification of the maker of the Northumbrian pipes (and to satisfy a personal curiosity), the author would greatly appreciate sources of any biographical information regarding Robert and/or James Reid. If you are aware of any such sources, please contact

Steve Bliven, South Dartmouth, Massachusetts

My thanks in advance.

1. Nicholas Bessaraboff, Ancient European Musical Instruments, an Organological Study of the Musical Instruments in the Leslie Lindsey Mason Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Harvard University Press, 1941. .

2. Lyndesay G. Langwill, An Index of Musical Wind-instrument Makers, Fourth Edition, undated, apparently self published (Lyndesay G. Langwill, 7 Dick Place, Edinburgh, EH9 2JS, Scotland

19

SOME ANTIQUE SCOTTISH SMALLPIPES by Alan Jones

This is something of a follow-up to the article we published in Issue 2 of the Journal. I’d like to show and describe some Scottish smallpipes I’ve collected over the past few years which have some definite historical value.

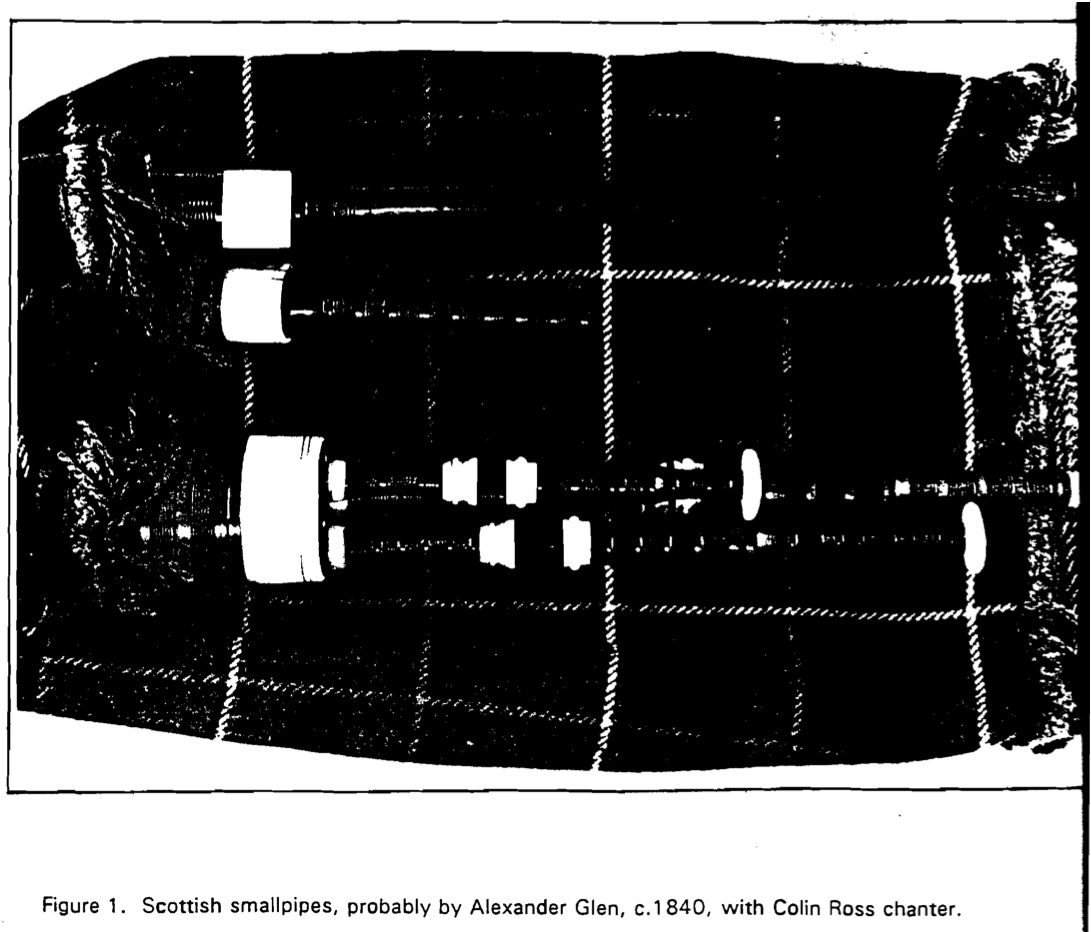

In Figure 1 is a set I obtained from Michael Hubbert in California. Colin Ross said that it was the only Scottish smallpipe he’d seen having a high fifth drone. Hugh Cheape of the National Museum of Scotland, who saw this set last October, said that the set may be the work of Alexander Glen, dating the instrument to the 1840’s. The combing on the drones is very interesting and the original chanter may be an early goose chanter, although we feel that the chanter is not of the same manufacture as the drones. The drones are of a brownish wood like Laburnum, and the original chanter was made of ebony. The chanter shown in the photograph was made to match the drones by Colin Ross in late 1990 and is pitched in C. These drones are very full sounding and have fairly large bores, which may explain why they seem to take a fair amount of air to play.

20

In the frontispiece of this issue of the Journal is a very interesting old set of Scottish smaIIppes with the wood sides of a beautiful old bellows. Notice the thistle design carved onto the inner cheek of the bellows. The metal fixtures do not appear too original. There are some very unique design features of the pipe components such as the ivory rings on the standing drone parts and on the stocks. All of the wood components are made of ebony. Hugh Cheape suggested that the set may date to the early 1800’s and the chanter may even be of an earlier manufacture.

I obtained the set through Dr. Richard Grimaldi of Schenectady, New York about four years ago. He had come by them from a local minister who found them in a garage sale in the Schenectady area. Gordon Mooney said that the chanter was very similar to the 1757 Montogomery set described fully in Common Stock (Vol 4, No.1, 1989, p.5) of which a working reproduction was later made by Julian Goodacre. Gordon found that the chanter size, bore dimension, and hole spacing was virtually identical. We tried an old cane Highland practice chanter reed in the chanter and he said that this was the reed to use in this chanter, having required only a little scraping. The pitch is around Eb to E.

Richard Grimaldi informed me that there had been a Macintosh bag (totally gunged up) on the set when he got it. This material was a new material in the 1920’s and was quite popular when it came out for use on Northumbrian pipes. I have subsequently noticed that the inside of the main stock is coated with a red oxide, possibly to seal up a crack.

In Figure 2 is a partial set which I obtained from David Burleigh, the Northumbrian pipemaker, whilst on a visit to Northumberland in October, 1991. What there is of the set is very beautifully made, notice that the main stock is Quite elegant. David told me that the set came originally from the workshop of Henry Starck, in London and that he (David) had received it from a pipemaker in Northern Ireland. Hugh Cheape dated the set as being from the late 18th century – 1790 to 1820, at the latest. Gordon Mooney observed that the chain is not a very Scottish component and that its presence may indicate that the set may have come from the English side of the border (although the chain may have been a later addition). The addition of silver chains to pipes was a fashionable thing to do in the early 19th century.

Following up on Gordon’s comments, notice the long recessed diameter at the end of the chanter. This actually resembles the recess turned on modern Northumbrian chanters to carry the closed sole. Food for thought, eh?

21

22

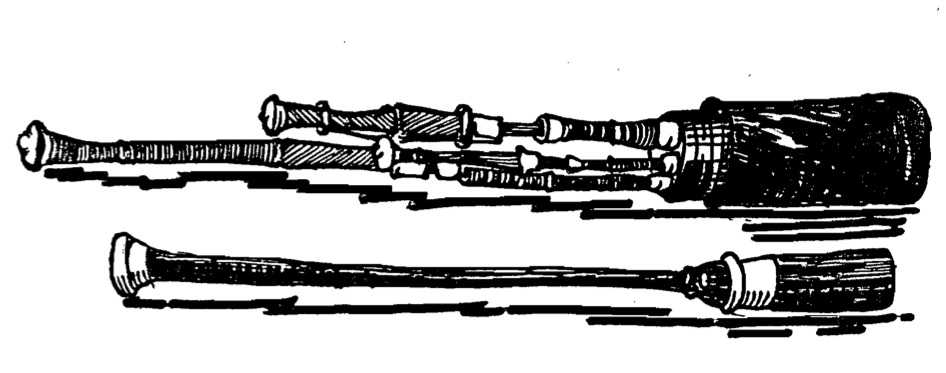

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONG PIPES by Denis Brooks

This article was originally published by the Piper’s Club, Cumann Na b ‘Piobairi, in the Piper’s Review, 1981. As you will see, it is an enlightening comparison of three Pastoral pipes, putting them in historical context with the Irish Union or Uillean pipes.

In past issues of the Piper’s Review there have been quite a bit of materials about the early Eighteenth century Irish pipes. This pipe was no more than a bag, bellows, chanter, and more often than not, two drones (bass and baritone) mounted on one common stock.

The chanter was not the same as our chanter of the last 200 years. It differed in that it was nearly half again the length, that greater length taken up by a “foot-joint”. A foot-joint is a detachable part of several types of wind instruments, Because it is detachable, the instrument is more easily transported in a smaller carrying case. But that is only a practical adjunct of the real reason for the foot-joint – the ability to alter acoustical aspects of the wind-column and to bring one or more lower tones in tune, by use of a tuning tenon (slide),

It must be assumed that the bellows-blown early Irish pipes evolved from the old Warpipes, an instrument which had two drones (a bass and a second drone an octave higher), and which had a chanter that could produce but nine notes, a’ to a”, and with a g’ below the a’, The instrument’s drones were tuned to a and A. When the early Union Pipes developed, the equivalent of the low g’, the leading tone (subtonic), was retained. If we merely reduce the old Warpipe pitch downward by five tones, we would have two drones, one in D, the other in d, and the chanter would scale d’ to d” (plus an octave to d”’), with a c’ leading tone. the c'(and c”‘) of the old chanter sounded through the foot joint.

John Geoghegan’s tutor, published ca. 1746, illustrated the long chanter (i.e., a chanter with foot joint.) By 1800, the famous O’Farrell did not mention it, and the instrument’s lowest tone was d’. What happened?

Between 1746 and 1800 the first regulator was added to the pipes. Pipes with two and three drones, the long chanter, and one (only) regulator were known in lowland Scotland and, it seems, even in Northumberland. But the instrument’s appearance in these areas was unusual. They never “caught on”. In Ireland, the foot joint was simply abandoned, It could have been because the foot joint was inclined to take leave of the chanter, and it was found that the chanter’s two lower notes were altered to D and D”, alright to play against the D drones, or that by ridding the chanter of the foot joint, the regulator was more easily got to. Remember, the length of the long chanter totally precluded any on the-knee playing (which couldn’t have produced clipped notes anyway, because of the non-fingerable vent hole in the foot joint), the pipes played in a standing position or, when sitting, the chanter directed downward between the legs. Whatever the reason for the ‘distempering’ of the chanter, the result was that the chanter could be played open and closed, and the regulator(s) could then be more easily availed of. It is likely that the foot-joint was discarded in Ireland ca. 1760. Paddy copped-on, the others gave up the pipes as a bad job.

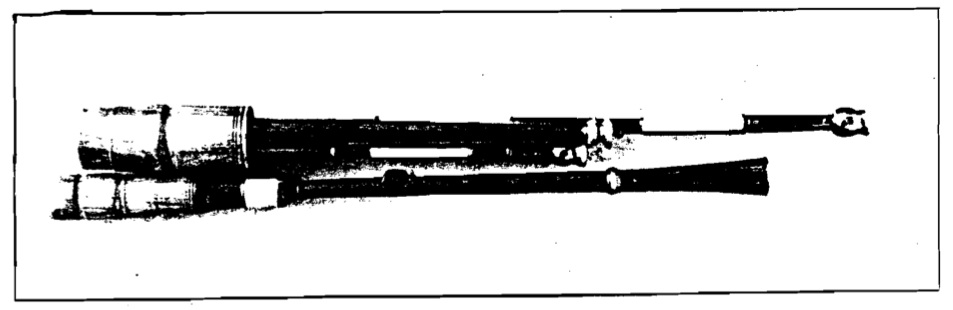

On the following page are shown three chanters of bagpipes formerly known in Northumberland as “Long Pipes”; William Cocks didn’t know what he had when he couldn’t identify the Long Pipes, and described the long chanter Union Pipes as “Hybrid” Union pipes. Same item. In a letter penned by Jack Armstrong, Piper to the Percy’s of Alnwick Castle, from the mid-fifties, he wrote that they had small pipes and half-long pipes, and if we carry on an inferred logic, there must have been long pipes. So, as we have just seen there were indeed “long pipes”, but, as might be inferred from Armstrong’s commentary, they were so uncommon as to be virtually known.

23

24

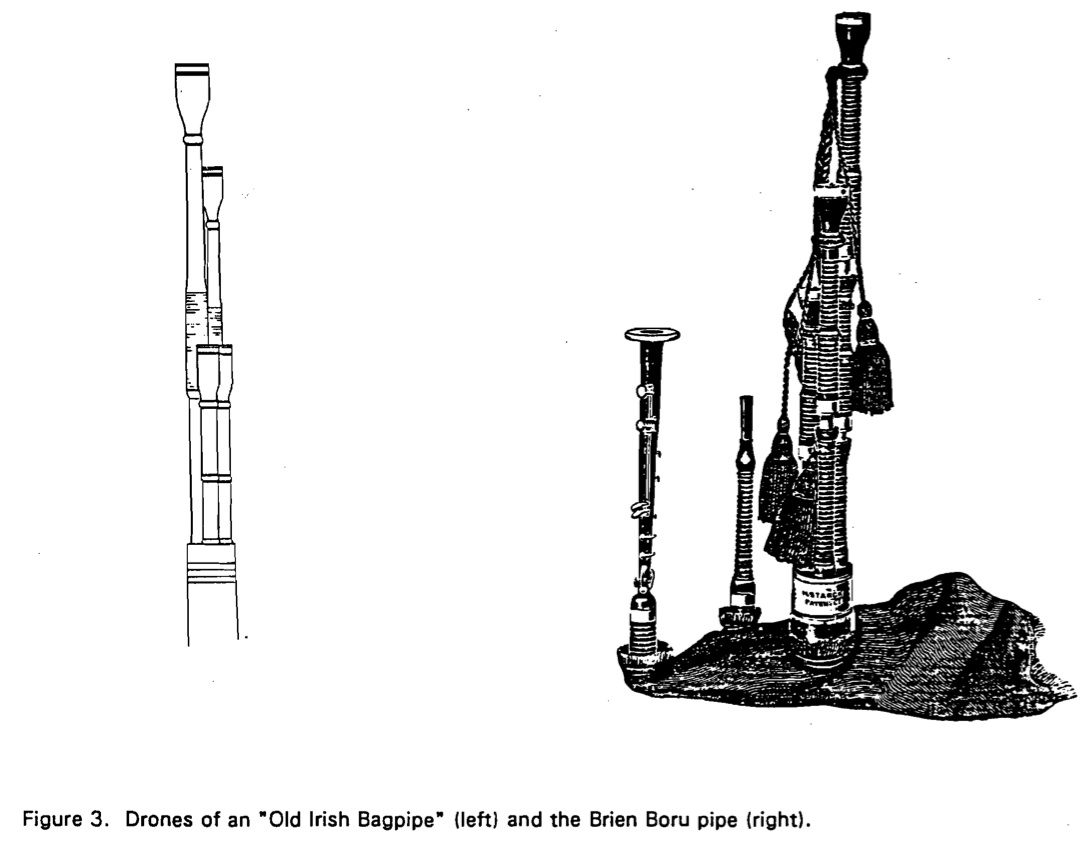

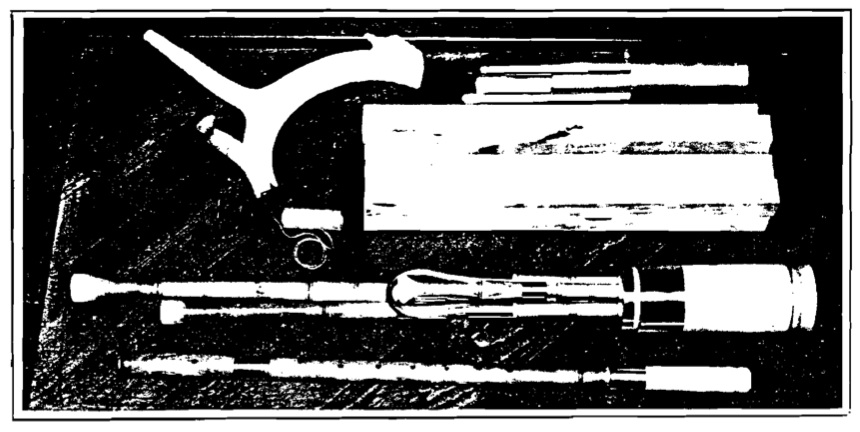

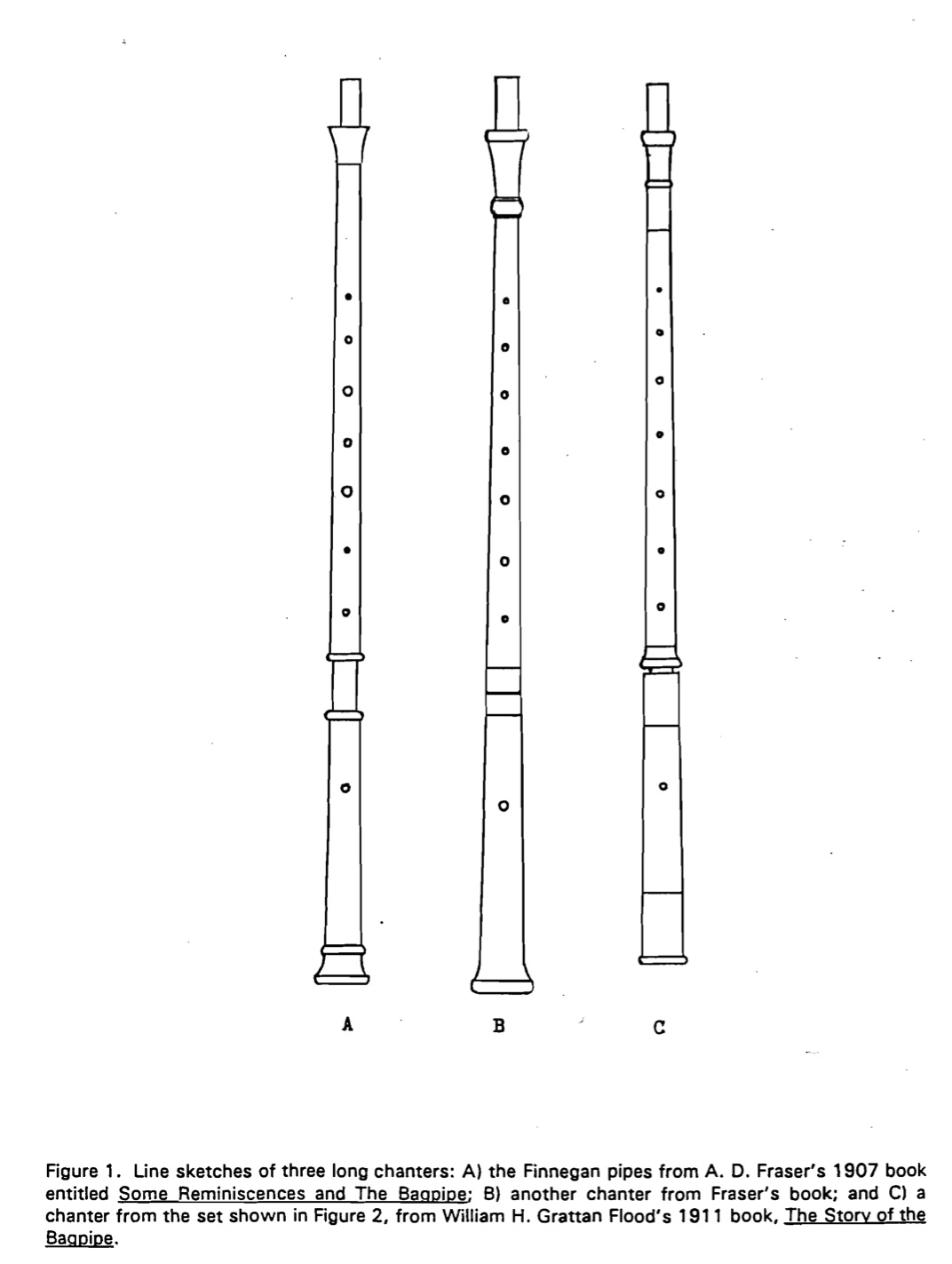

Of the chanters shown in Figure 1, A is a reproduction of the chanter of a set of pipes in A.D. Fraser’s book Some Reminiscences and the Bagpipe, Edinburgh, 1907. The pipes are styled “The Cuisleagh Ciuil of Ireland”. They have the usual three drones (all straight) and a five key regulator. Inside the bag cover was found a receipt: “Archd. Wilson Bought off Arthur Finnigan, Broker…” Glasgow, ca. 1800. They were silver mounted and cost 3.0.0. pounds (!). Thus, Finnigan’s Pipes: was Finnigan an Irish agent? I think the circumstances support the hypothesis that this pipe was Irish and, therefore, that this particular chanter was yet known in Ireland in the later Eighteenth century.

Chanter B also in Fraser, is that of an “Old Irish Bagpipe”. Fraser wrote that Canon Goodman said: “No such pipe has been played in Ireland for at least 200 years”. For a multitude of reasons, this comment must have been tendered shortly before his death in 1896. The feature which is really foreign here is the four drones, all massive and with large chalice style bells. There are two short drones, equal length, lacking slides, which may have been fake [often referred to as dummy drones]. The two large drones are nearly the same length, and ratio is about the same as in the pipes in the Duckett Collection (O’Neill: Minstrels and Musicians, p.44) of ca. 1770.

Also the drone lengths of the J. Egan set in the hands of Denny Hall, about which we wrote two Reviews ago [republished in Journal # 3 of the N.A.A.L.B.P., page 30], are of the same ratio. Why? Because the bass, which in a straight form would be nearly double the length of the middle drone, is recurved within the main stock: the Duckett pipes and many others of the ilk of Denny Hall’s pipes (late Eighteenth century) are recurved externally, one joint of the recurve occurring within the main stock. The coarseness of the drones, and the general design, cause speculation that this Old Irish Bagpipe was in fact a genuine (Northumbrian) Long Pipe or, if you wish, a Lowland Scots Long Pipe [read there, Pastoral pipe]. The drone style is exactly the same as that of the Northumbrian Half Long Pipes, the same style which pipemaker Henry Starck used as a model for his creation of the so-called Irish Brian Boru Pipes, A-D-A drones on a common stock accompanying a lengthened warpipe chanter with keys to produce a compass e’ -c”’. But the long chanter, yes, it had a metal tuning slide for the foot-joint. It would seem that chanter B was merely an “Irish” chanter wedded to border-style drones.

Chanter C appears in William H. Grattan Flood’s The Story of the Bagpipe, New York, 1911. The Wexford man goes quite awry here. Figure 2 shows Flood’s Plate B (opposite to page 192) and is of a “Set of bagpipes, probably old Northumbrian – Eighteenth century. There are no keys on either the Chanter or the Drones”. When were there ever keys on drones? But read here regulator. Close examination makes it clear that this set of pipes had one regulator of four keys. There were two drones (maybe a small one hidden by the body of the pipes in the plate). The bass drone is quite short, perhaps again due to a recurve within the main stock. The drones could be either Irish or Northumbrian. The chanter in the plate is shown inserted into the stock upside-down and has a foot joint (albeit attached to the stock tenon). I have altered this error in the line drawing of Figure 1 C. The chanter appears to be Irish, but could be of British manufacture. The point is that the chanter varies from A and B but little! The three chanters are given here from some of my old sketches· the comparison of overall length based on the distance between the top-most and lower-most finger holes.

The data show that, once again, the long chanter had a short and regionally indeterminate life span. Because the Finnigan pipes, by implication of family name, and the pipes of Geoghegan’s tutor, 1746, and family name, are similar, and the ambiguity of general references to the Long Pipes are so great, one must conclude that the chanter of the virtually and historically unknown Northumbrian Long Pipes (Cock’s Hybrid Union Pipes), and Geoghegan’s pipes were naught about the early Irish chanter. In the case of Scots and Northumbrian drone configuration and tuning, the Irish chanter (perhaps Geoghegan’s or an immediate predecessor’s modification of the warpipe chanter) was merely used to replace a local chanter, or the Geoghegan pipes were borrowed outright. Thus Canon Goodman unwittingly came close to the truth about the Old Irish bagpipe: in fact, it had never been found in Ireland.

25

Thus far, the drones have been mentioned coincidentally to the chanter. It should be known that the original Northumbrian Small Pipe chanter was most likely a simple reproduction of the French Musette chanter which appeared as part of the French pipes in Northumberland, if not first in London, during the late seventeenth century. The French drone system was unusual, one of a series of interconnected bores within a cylinder about six-seven inches long. The drones were reeded with double-bladed chanter type reeds and were tuned by means of sliders or shuttles on the face of the cylinder. This “shuttle” drone was given over in favor of the usual, separate, straight drones using single bladed reeds. What did happen though, was the retention of the French tuning system in octaves and fifths (or fourths) and the emplacement of the straight drones in a common stock. The longer two drones of the “Old Irish Bagpipe” were probably tuned in octaves. The drones of the Brien Boru Pipes were tuned in octaves and a fifth, reminiscent of the Northumbrian pipes. Irish drones, quite obviously, were attached to a common stock, too. Thus the Northumbrian folks changed the form of the French drones and put them in a common stock, but retained the French tuning. The Irish retained the Northumbrian drone form, but changed the tuning to straight octaves. The bellows, too, is likely of French origin.

Thus far, the drones have been mentioned coincidentally to the chanter. It should be known that the original Northumbrian Small Pipe chanter was most likely a simple reproduction of the French Musette chanter which appeared as part of the French pipes in Northumberland, if not first in London, during the late seventeenth century. The French drone system was unusual, one of a series of interconnected bores within a cylinder about six-seven inches long. The drones were reeded with double-bladed chanter type reeds and were tuned by means of sliders or shuttles on the face of the cylinder. This “shuttle” drone was given over in favor of the usual, separate, straight drones using single bladed reeds. What did happen though, was the retention of the French tuning system in octaves and fifths (or fourths) and the emplacement of the straight drones in a common stock. The longer two drones of the “Old Irish Bagpipe” were probably tuned in octaves. The drones of the Brien Boru Pipes were tuned in octaves and a fifth, reminiscent of the Northumbrian pipes. Irish drones, quite obviously, were attached to a common stock, too. Thus the Northumbrian folks changed the form of the French drones and put them in a common stock, but retained the French tuning. The Irish retained the Northumbrian drone form, but changed the tuning to straight octaves. The bellows, too, is likely of French origin.

Further, the drones of the Northumbrian Half Long Pipes were enlarged to conform to the size of the Highland Scots or Irish Warpipes, but, again, the tuning remained in the octave – fifth pattern. The chanter, however, was merely a Highland one. It is a moot point now whether or not the Half Long pipes were actually Scots Lowland pipes with the octave drones changed or that the Half Long pipes actually were the source and inspiration of the Lowland Scots pipes. In either case, they were never very popular except in a few districts of the Scots lowland or border districts (hence the Half Long pipes have often been called Border Pipes).

26

The next phase of early evolution was substitution of the Long Chanter for other chanters. In the case of the Irish pipes, the drones, having never been changed to the octave – fifth tuning and numbering but two (as in the warpipes, and tuned in octaves) as opposed to the three drones found in Britain, were soon augmented by a small, third drone. This has remained a standard feature of the Irish pipes. The regulator would likely never have appeared were it not for the early borrowing of the common stock. The older pipes, here those which were part of the three long chanters illustrated in Figure 1, were the products of skilled instrument / bagpipe makers, men interested in improving their art and therefore learning new aspects of the art from others. Irish pipemakers were in Northumberland early in the Nineteenth century and may well have been there much earlier. However, it cannot be stated without contest that the early Union pipe was developed only there, or only in London, or that the Union pipe was the result of several efforts. We can say only that the chanter and the regulator are Irish, and quite probably, that the drones are merely part of the overall development of the -New- or -Improved- or ·Pastoral- bagpipes. Below is shown the drones of the “Old Irish Bagpipes” and a set of “Brien Boru Pipes”. Note the common stock of both instruments and the large drone bells (ends). These are not Irish at all. There are no historical data to confirm other than they were originally Scots-English, if you’ll pardon the expression. Irish warpipe drone bells were smallish. Typical Irish Union pipe drone bells are also smallish, though the general form may also be foreign. Old Scottish and Irish warpipe drone bells were flared sharply, not chalice or tulip shaped. If you believe that this exchange is rather too complicated, where do you imagine that the bass drone “trumpet” or “trombone” slide came from? It is merely another adapted part of general instrument making technology.

27

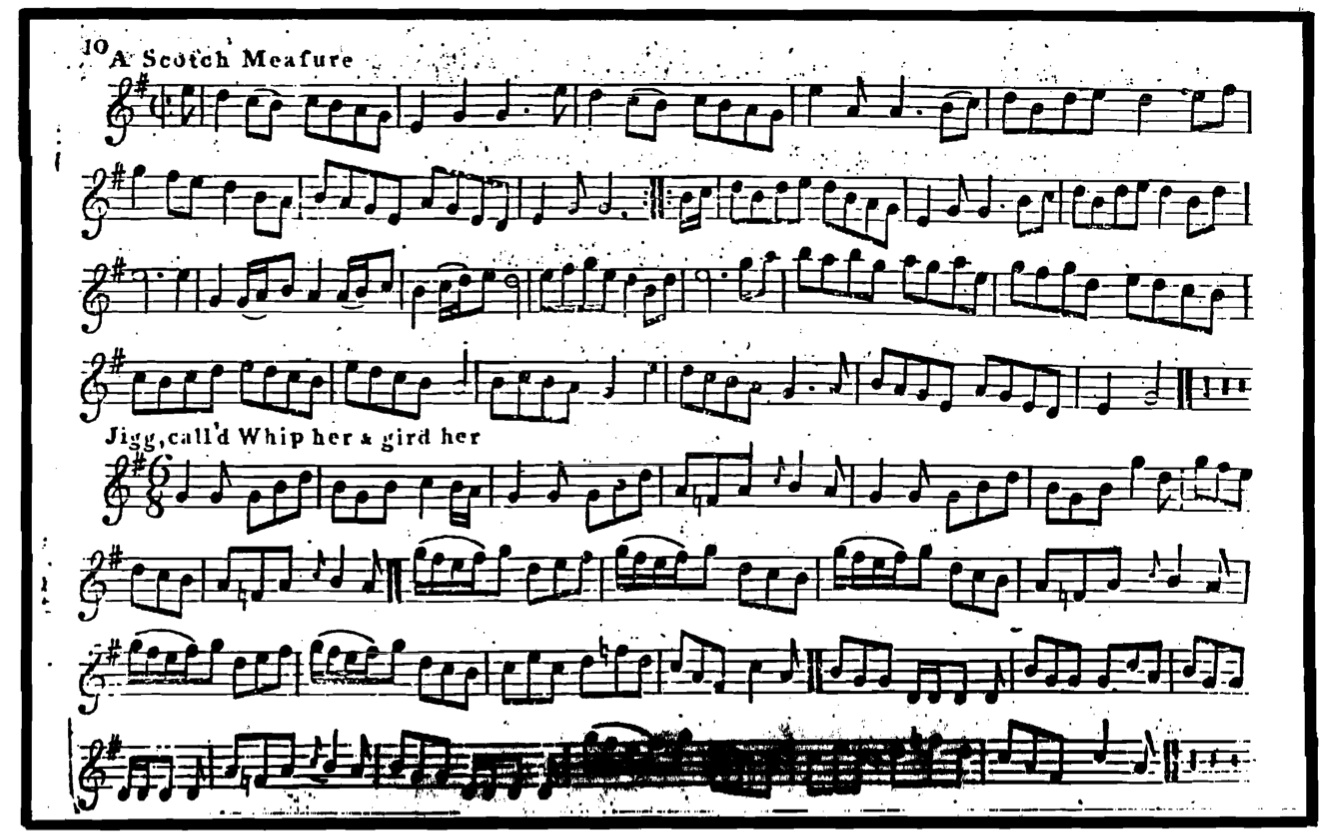

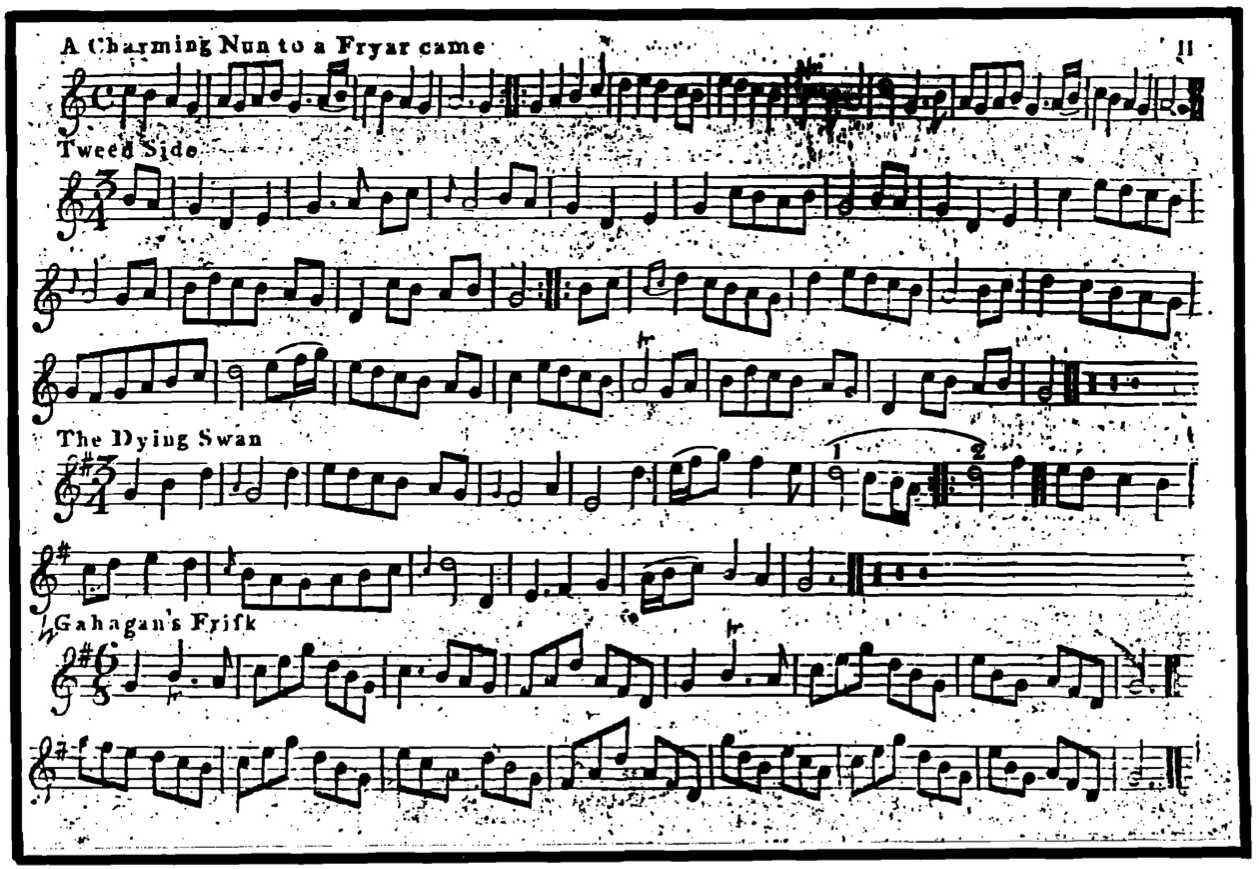

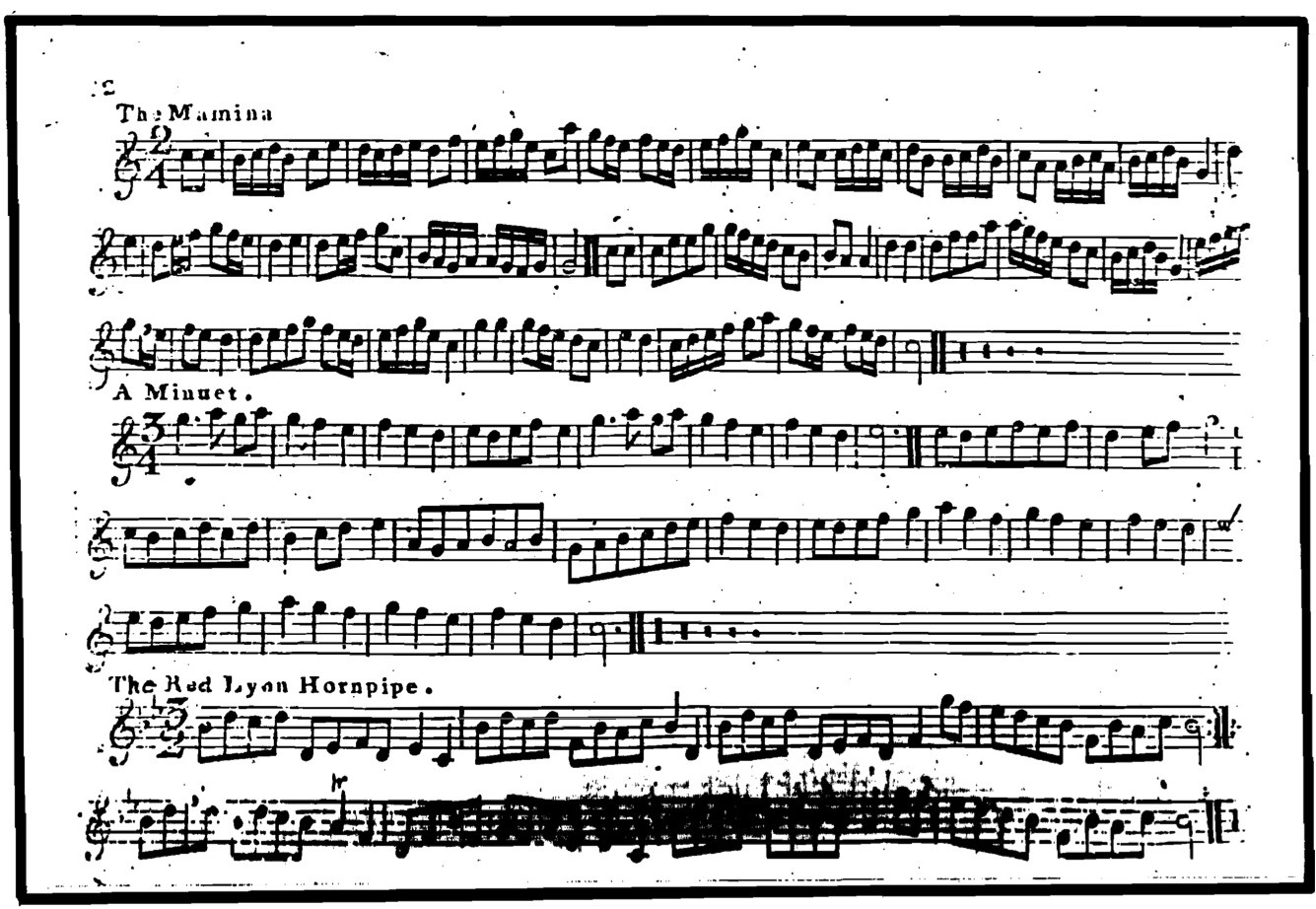

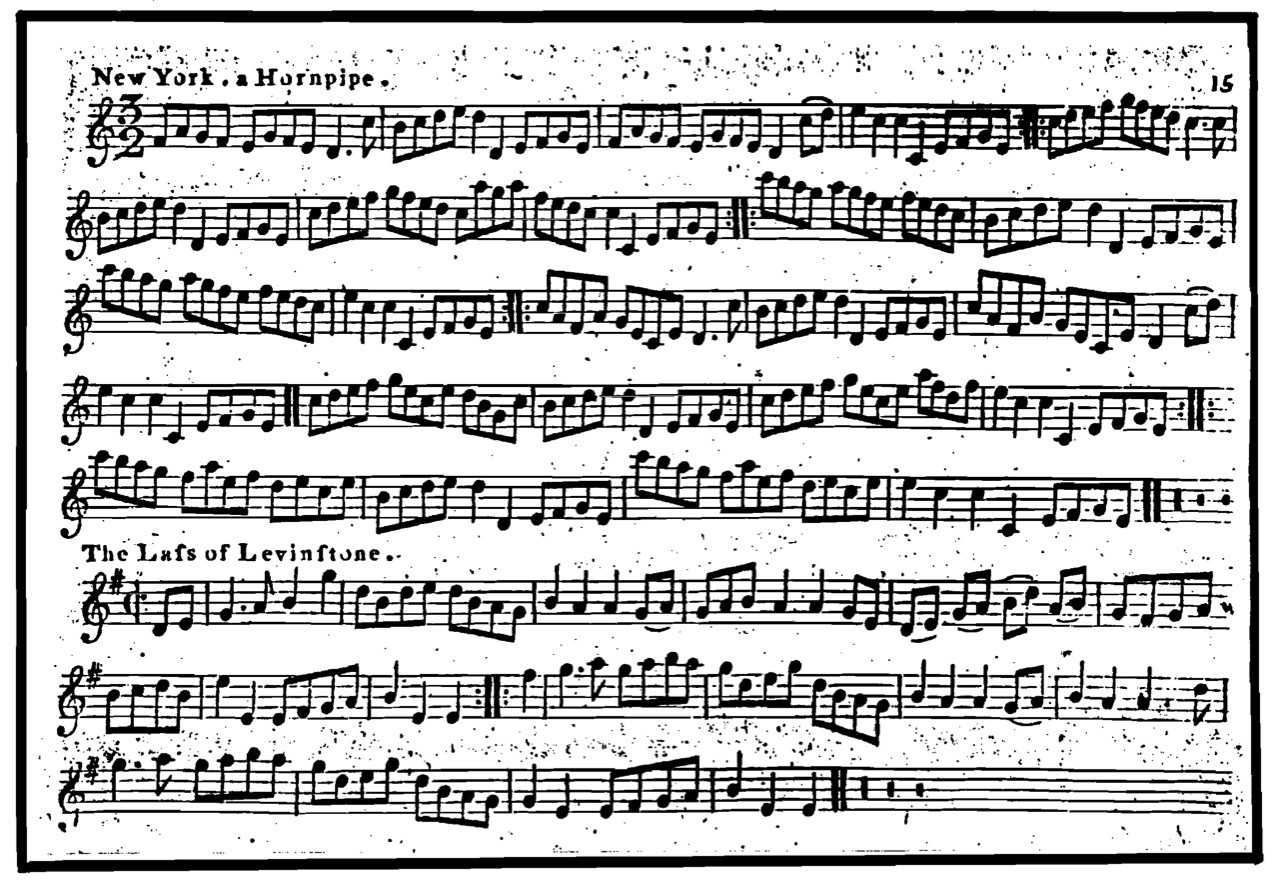

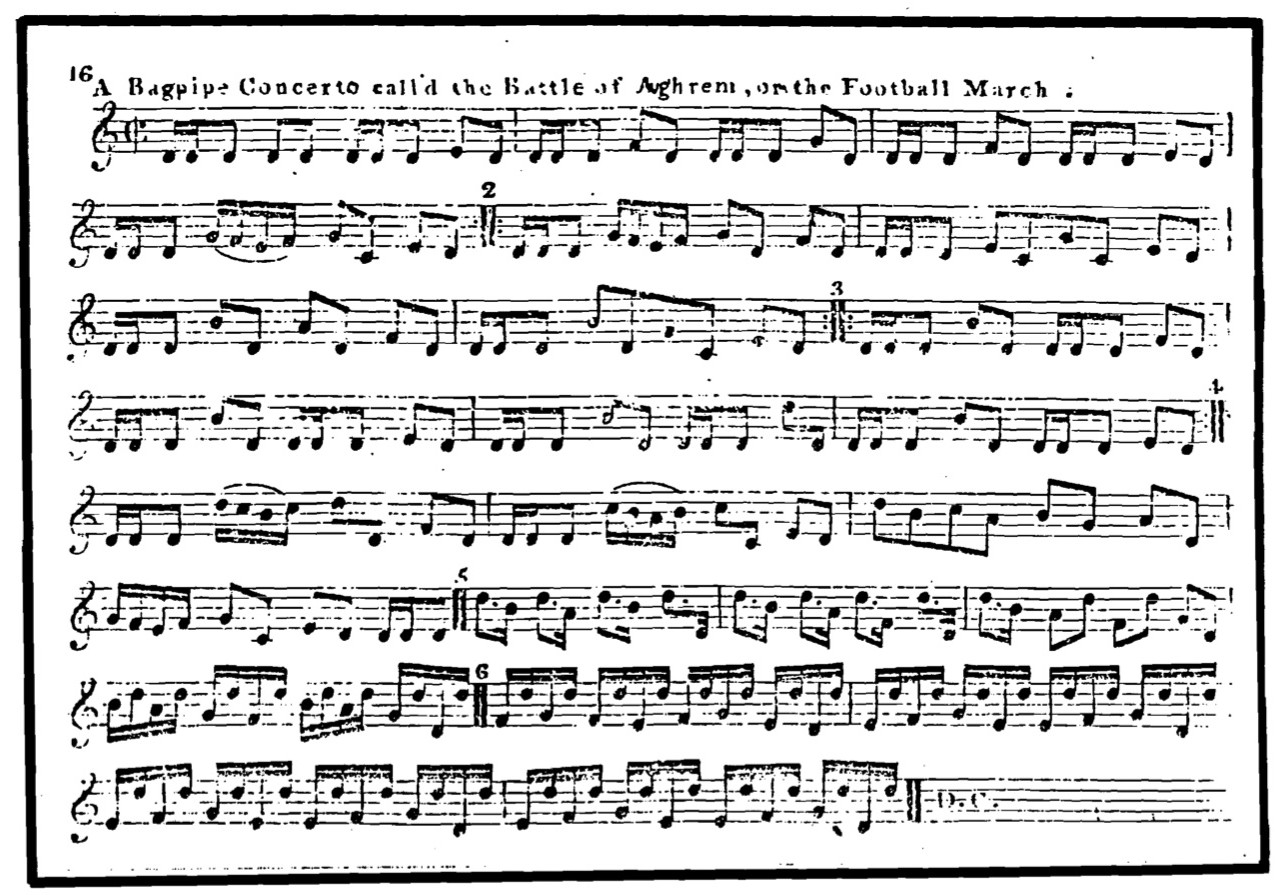

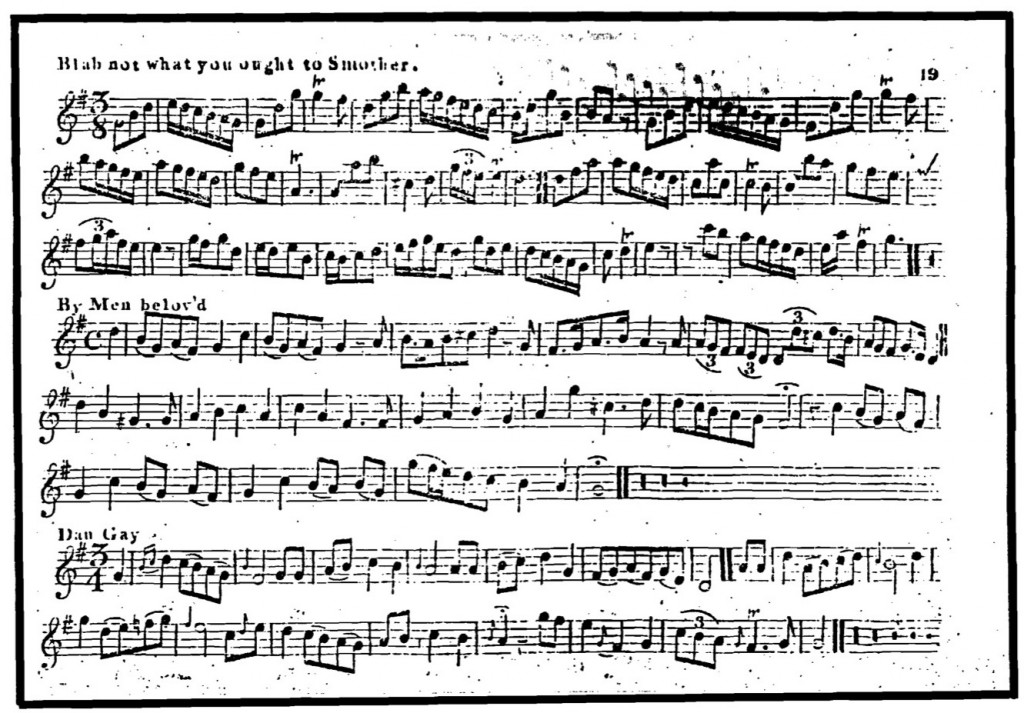

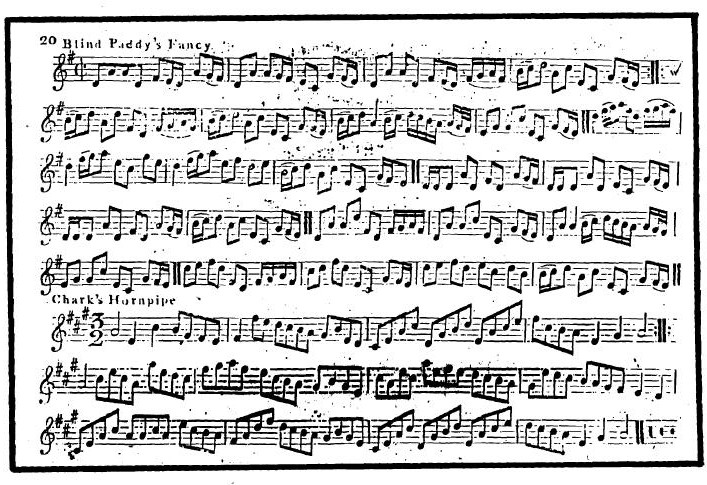

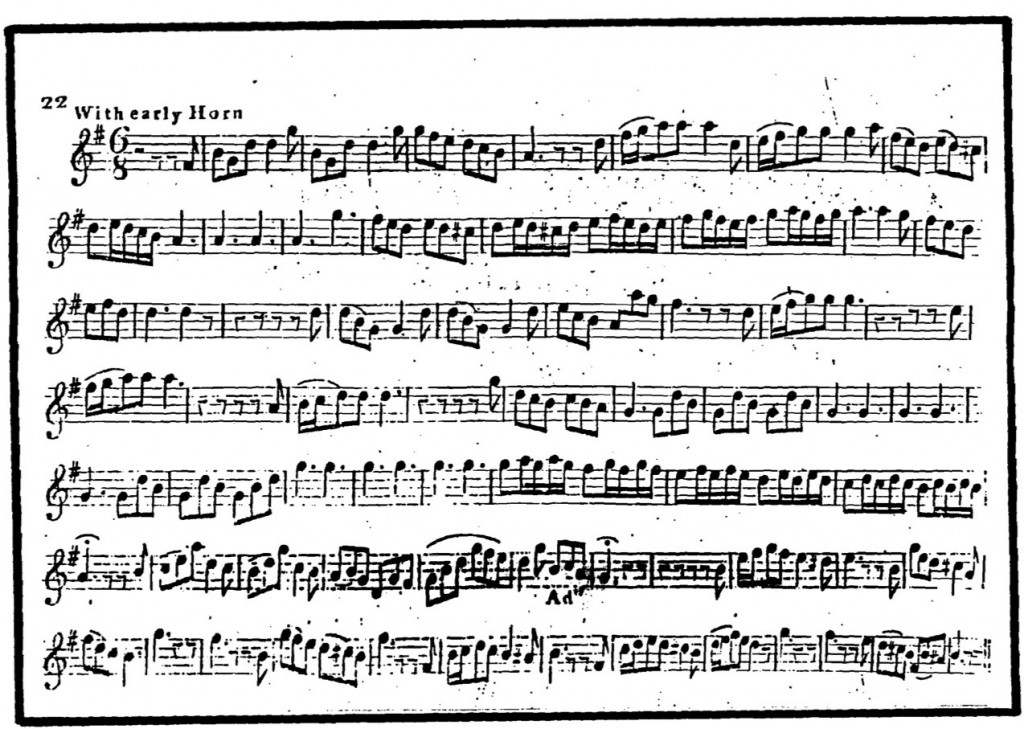

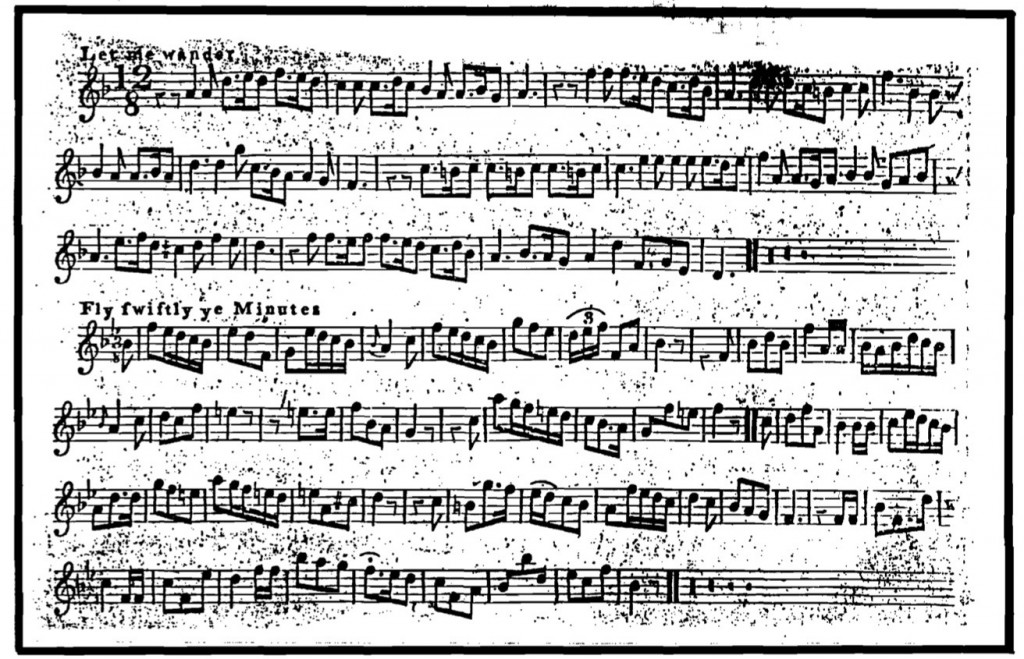

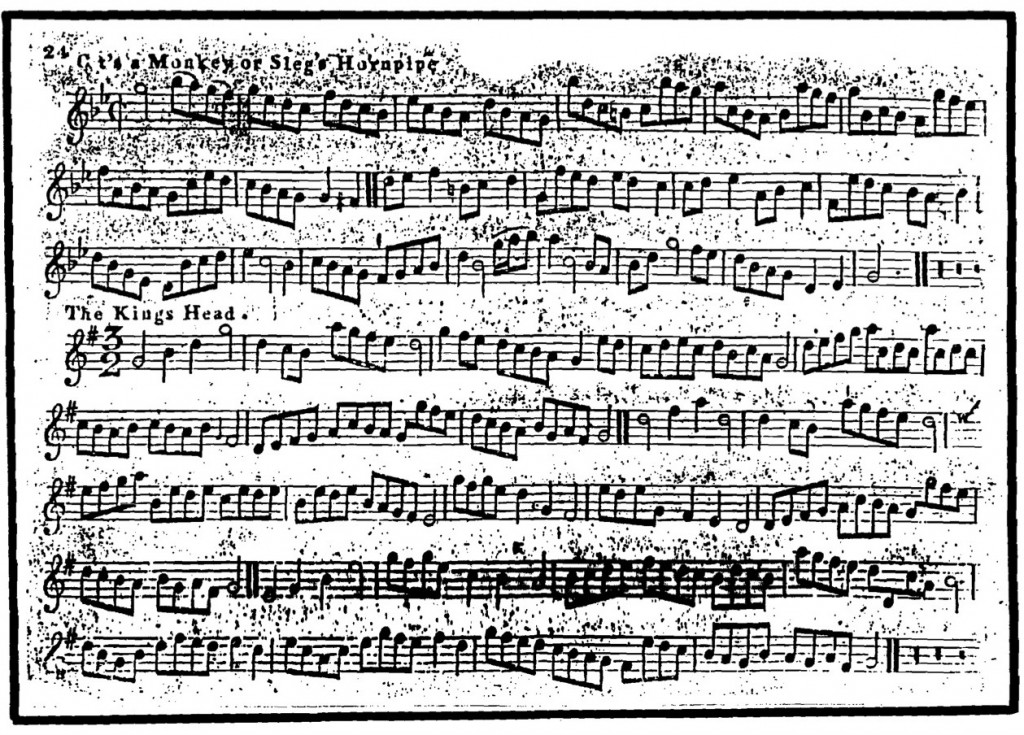

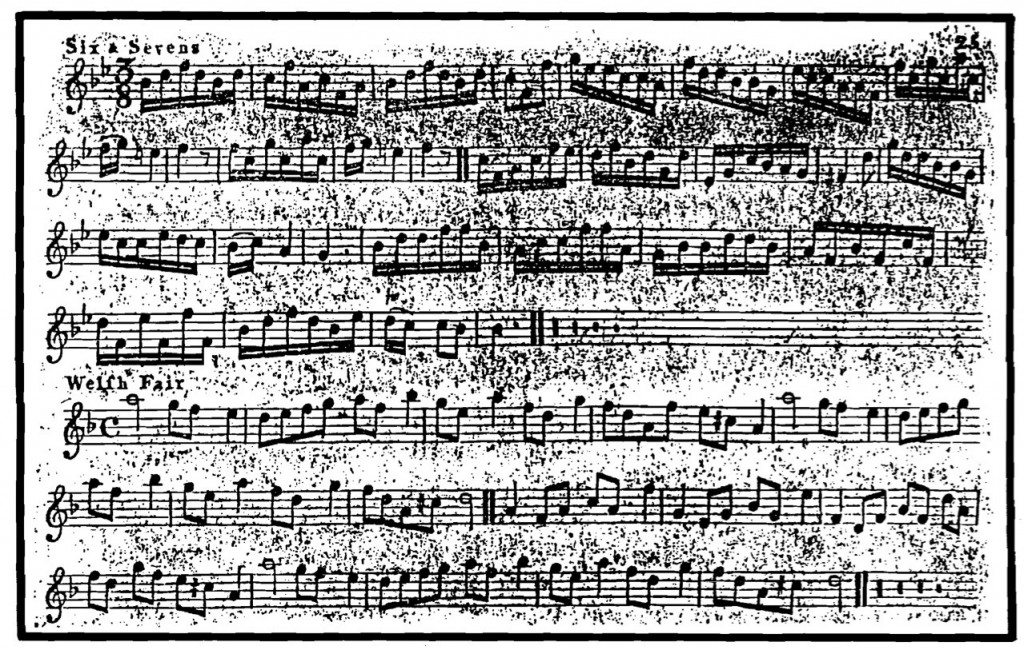

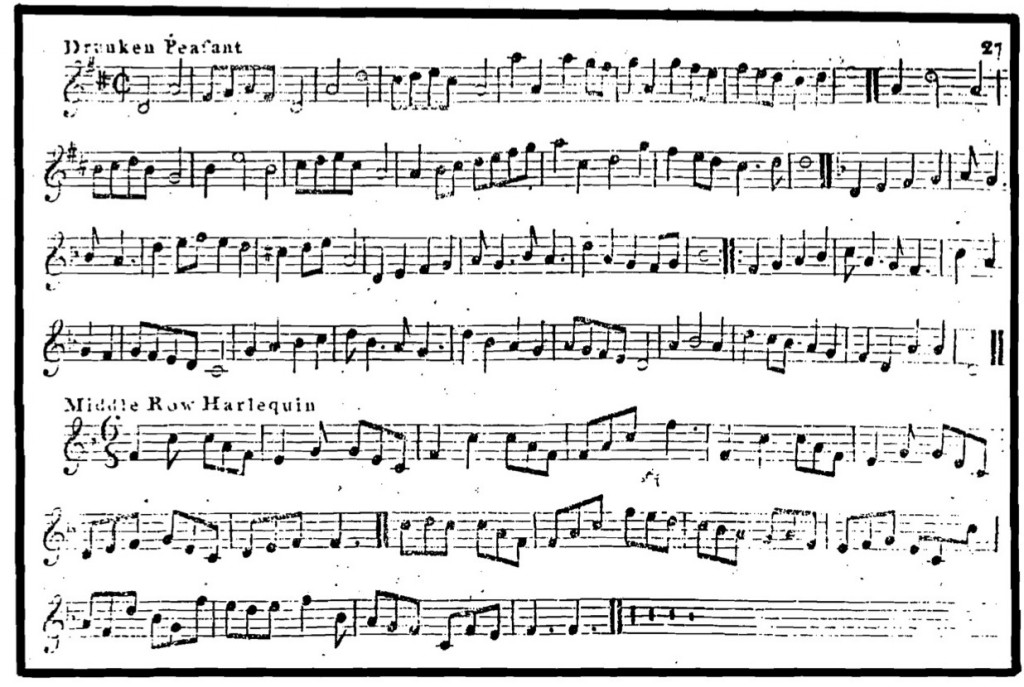

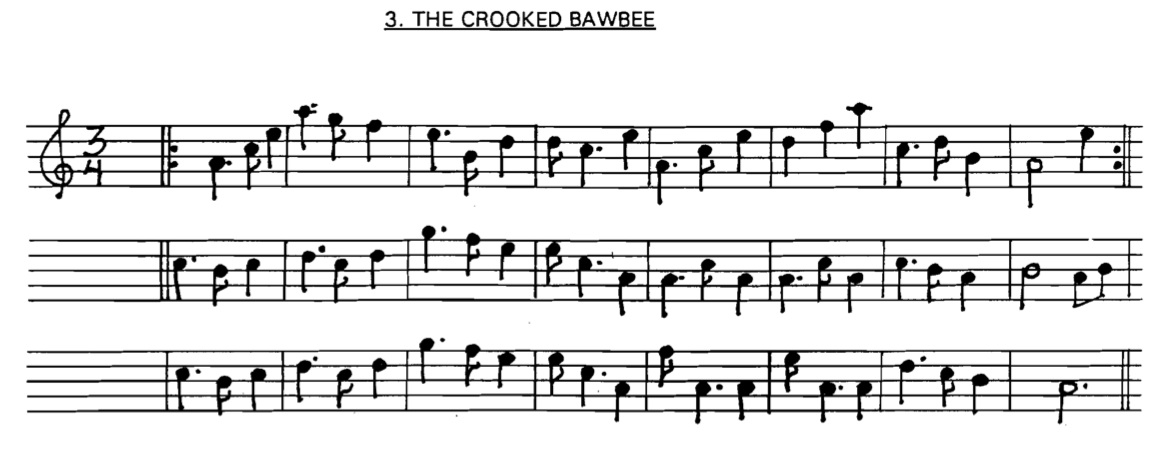

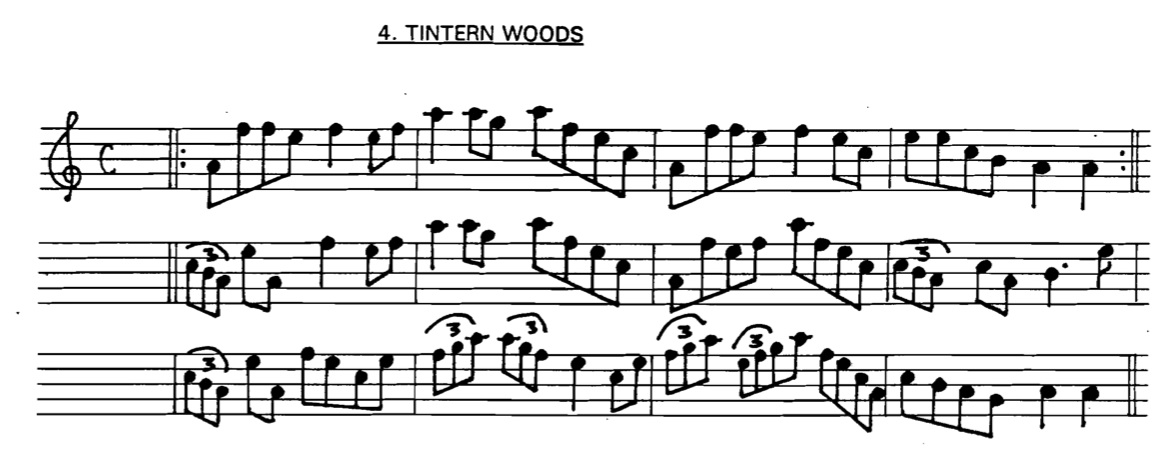

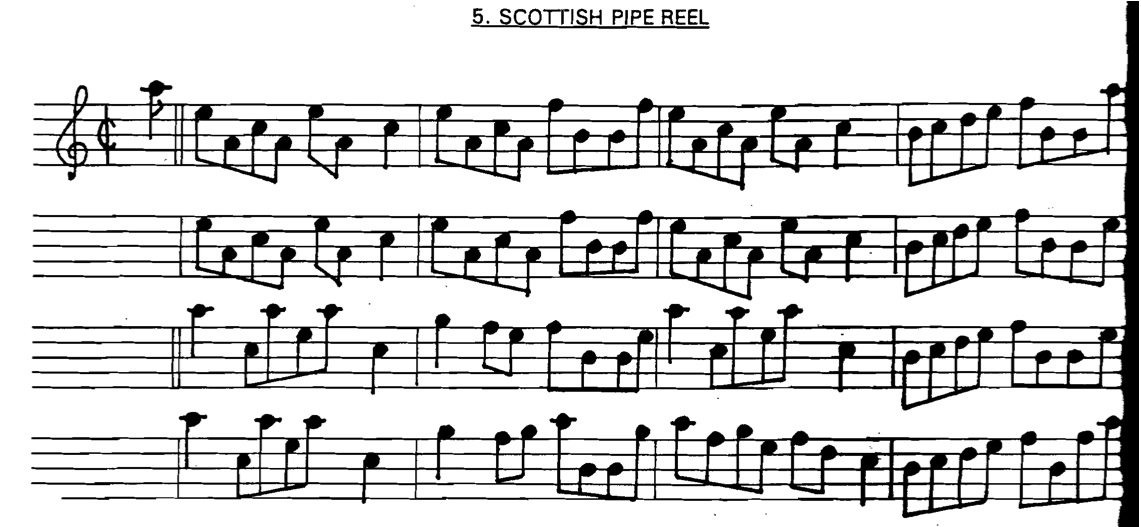

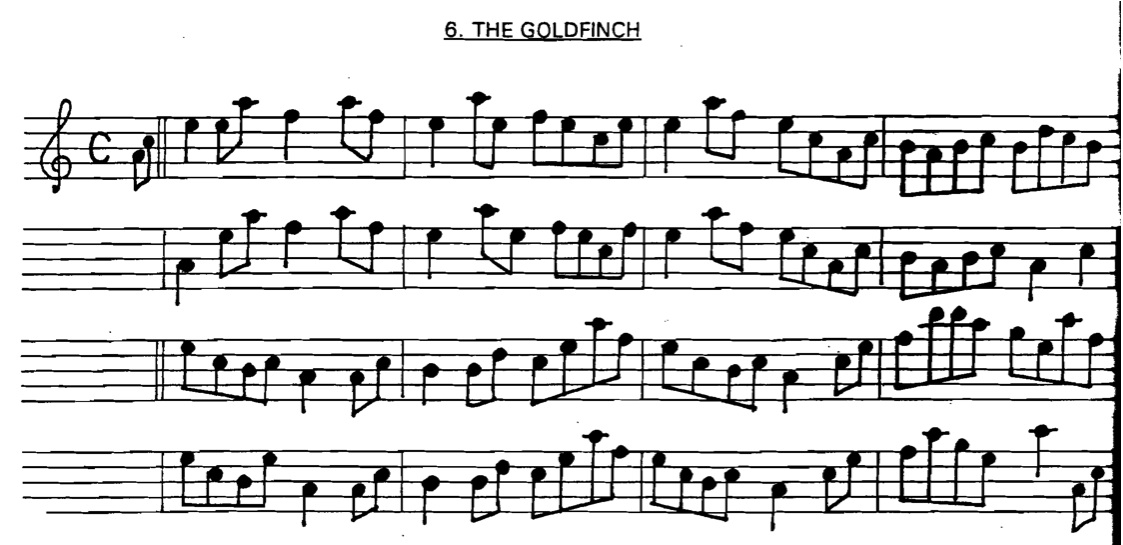

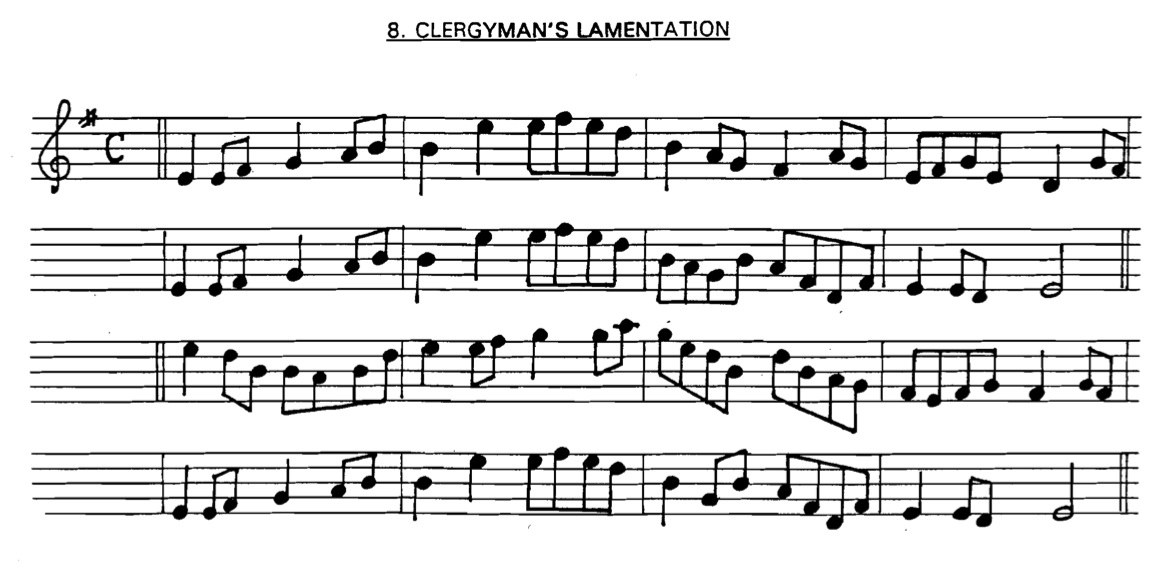

GEOGHEGAN’S TUNES

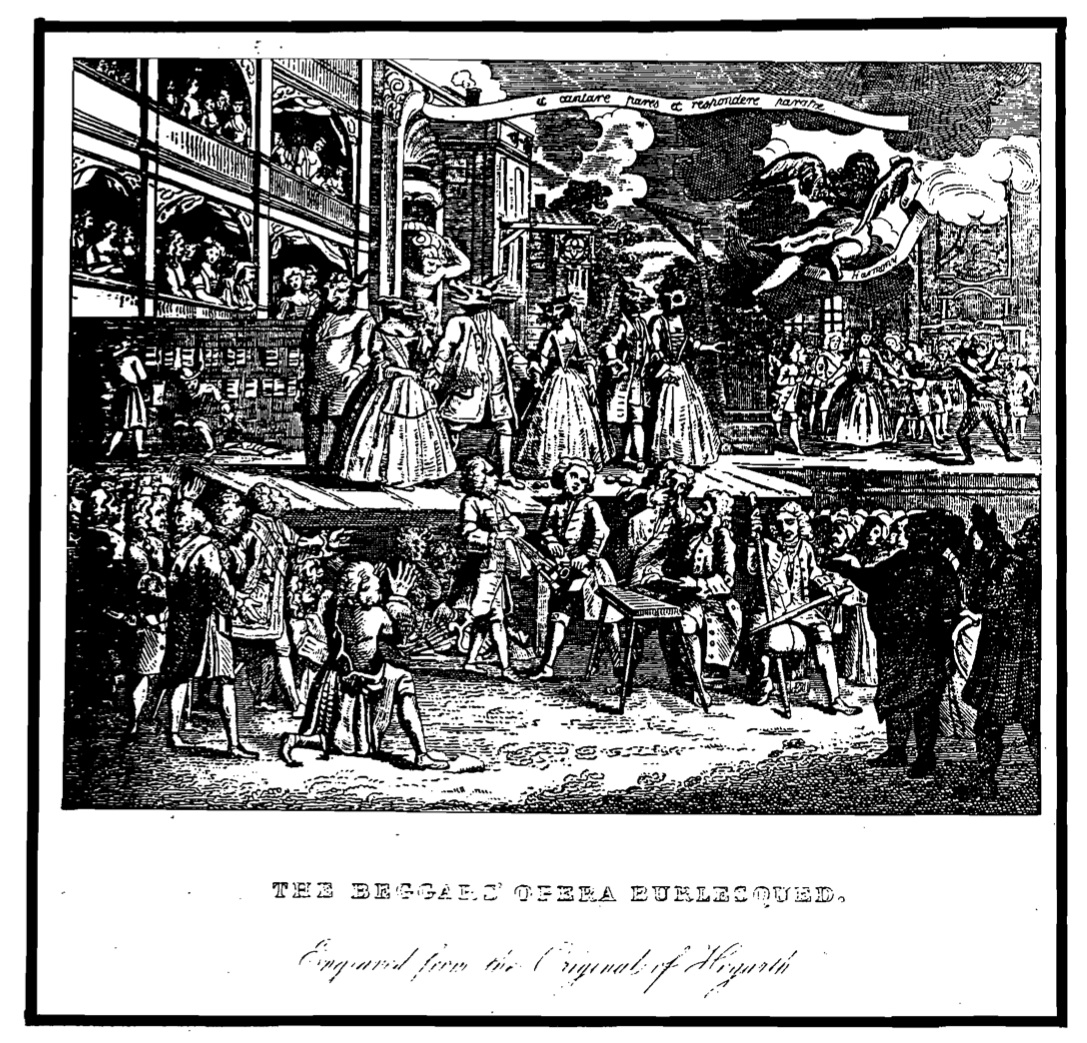

Following are the tunes from the Simpson Edition of John Geoghegan’s Compleat Tutor for the Pastoral Or New Bagpipe. The tutorial section of the book was printed in Issue 3 of the Journal (August 1991, pp. 9 – 201). Below is a contemporary drawing by William Hogarth (1728) of the Pastoral pipe seen in the context of ‘The Beggar’s Opera Burlesqued’ (from Bagpipes in English Works of Art, by R. D. Cannon, in The Galpin Society Journal, No. XLII, 1989, p.21). An engraved interpretation of the work (unsigned and undated) appears on the next page (sent in by James Coldren and Andy Rosen).

[APNA Editor’s Note: The following printed music suffers from being copied too many times and is illegible in some places. A different Geoghegan edition, but with more readable music, is available on Ross Anderson’s Music Page here. Scroll down to Pastoral/union/uilleann and Northumbrian pipe music, and Geoghegan’s is the first one. Be sure to check out the wealth of hard to find bagpipe music and research works on Ross’s site.]

30

37

38

39

41

43

44

47

48

49

************

50

LOWLAND PIPE NOMENCLATURE by Ray Sloan

I was very interested to read Brian McCandless’ article in Issue #1 of the NAALBP. I have myself recently been working on a manual for the Small-pipes which is to include a historical section and inevitably will take in their close relatives, the Lowland pipes and Half-longs. The reason for writing this article is that I am, as it were, already in gear for this discussion, and Mr. McCandless’ article raised one or two points of contention in my mind.

I prefer to approach this whole question of bagpipe terminology as it applies to our present day understanding of the pipes in question, As a pipemaker I constantly come across confusion in customers over what to call a particular pipe. I have had people for example almost ordering Small pipes when what they were really after was Lowland pipes. Controversy and misunderstanding is not new to the world of piping, indeed they seem to be inextricably linked! In his 1911 work The Story of the Bagpipe (1) Grattan Flood opens Chapter XXII with the following:

“Much misconception has existed with regard to the Lowland Bagpipe as distinct from the Highland. Some writers allege that the two instruments are totally distinct, and that the Lowland Bagpipe is rather of an inferior class”,

This sentiment is also echoed in the accounts of these pipes being called “common” in R. D. Cannon’s authoritative book The Highland Bagpipe and its Music (2). And so, if nothing else, I hope to contribute to the collective controversy of pipers.

I hope that I can further simplify our understanding of what is what in this article by reducing Mr. McCandless’ list of bagpipes for convenience to just four types and two categories – all of them being bellows blown. I must say at this point that I am not concerned here with the Pastoral pipes, only: 1) Lowland pipes; 2) Northumbrian Half-long pipes and; 3) Small-pipes. Now I have heard people talk about the three types of pipes listed above as: Border pipes/Border Half-longs/Northumbrian Halflongs/Lowland pipes/Lowland Half-longs/Scottish Small-pipes/Scottish Lowland Small-pipes/Border Small-pipes/Northumbrian Small-pipes and in earlier years Hill pipes and the Northumbrian Large pipes (Half-longs). I think. you must agree that this is pretty confusing since the natural tendency is to believe that each label is an individual pipe. There are just two categories of pipe here, both bellows blown, which can be separated by chanter construction. On the one hand the are the Lowland and Half-long pipes characterized by a conically bored chanter and the quite different Small-pipes which are cylindrically bored, except for the Scottish small-pipes which can have a slight flair at the bottom inch or two depending upon pitch. These can also be separated by reed type as both the Lowland and Half-long pipes are reeded with the basic, but modified ‘V’ shaped Highland pipe reed whilst both of the Small-pipes are reeded with the standard Northumbrian format of a parallel sided reed.

Mr. McCandless, therefore, is quite correct to use the term “Lowland Pipe” to refer to a broad category of pipe that posses a bellows, open ended chanter, and simple drones. However, I would suggest further that it is essential to add “open ended chanter of conical bore construction”. This then separates the Lowland pipe from the Scottish and Northumbrian Small-pipes. In my opinion, the term Border pipe simply adds to the confused plethora of terms and has all the other characteristics of the Lowland pipe. Thus Mr. McCandless’ category of Lowland pipe can be reduced to the Lowland pipe and the Half-long pipe, which are essentially regional variants of the same instrument. The variations appear in the chanter scale and the drone arrangement. The chanters of the Lowland pipe and Half-long ‘originally’ differed in that, as Mr. McCandless points out, the Northumbrian Half-long chanter had a sharp seventh whereas the Lowland pipe had the flattened seventh scale as in the Highland bagpipe. Beyond this scale difference, there is absolutely no difference in either fingering technique nor sound/tone quality save as what may be the result of the particular wood used in their manufacture.

51

I have looked at a number of Half-long pipes at the Bagpipe Museum in Morpeth, Northumberland, and all except one had sharpened sevenths. Nowadays Half-longs are produced with the flattened seventh scale typically used in Highland and Lowland bagpipes. The drones of the Northumbrian Half-long pipes are typically arrayed with the inclusion of a fifth interval drone, as with the Smallpipes, unlike the Lowland pipe which has the Scottish tenor/tenor/bass drone arrangement. At this point the story becomes historically interesting and takes in Mr. McCandless’ question concerning the curious term ‘Half-long’ (3). What does it mean? There is one thing that I can say with absolute certainty: no one knows! Like so many aspects of piping history and terminology the answers to such questions are left to informed guesswork – or otherwise. As for the suggestion that the term may refer to the shorter bass drones, I tend to think not and have found only one example of a bass drone which is shorter than the norm for Lowland or Half-long pipes. This is a set of pipes of 1772 which belonged to Muckle Jock Milburn of Bellingham. The bass drone is 5 cm shorter than other drones but the tenor drones are proportionally shorter also. I personally believe that the term is a relative misnomer and possibly even a very local term used to describe this Lowland pipe variant in Northumberland.

There are references in historical documents to two drone Lowland pipes, as there are two drone Highland pipes, and so it is one possibility that when the long bass drone was introduced the pipes retaining the two tenor drones, which are exactly ‘half as long’ as the bass drone got called…this is, however, pure unadulterated conjecture on my part, and in the absence of any better explanation, why not! Whatever the real answer I feel quite certain that it was a local term having little historical significance and I do not believe that the term necessarily implies an Older and bigger pipe in Northumberland. Looking to circumstantial evidence again in support of this I am equally certain that if either the ‘Half-long’ or an older pipe existed in any positive way then ~ certainly they would have been mentioned in ‘dispatches’ somewhere. So far, however, it is hard to find any old reference to even ‘Half-long’ let alone a bigger pipe beyond the early 1900’s. In Flood’s 1911 book I don’t believe that even the ‘Half-long’ is mentioned at all. Moreover, the term has obviously been the subject of some debate in the county.

52

This was the renaissance of Northumbrian piping in general and it was about this time that the bagpipe maker Robertson of Edinburgh began making the Half-Long pipes as we know them. There are one or two more points to make about these pipes relative to their redevelopment.

Robertson initially produced a number of Half-Longs with the true Half-Long chanter having the sharpened seventh. These were however withdrawn and replaced by chanters with the standard Scottish flattened seventh scale (6). The reason for this is not fully known but I suspect that this was because enthusiasts were by now used to the latter scale found in the more widespread Highland and Lowland pipes. The drones of the Half-Longs, however, as redesigned by Charlton, Cocks, et. aI., and as previously mentioned, remain and persist to this day in the form of tenor, baritone, and bass. Herein lies a fundamental error. The ‘style’ of the drones was indeed modeled upon Muckle Jock’s and James Hall’s pipes, but the format was quite wrong. I have looked at in excess of 14 sets of antique Lowland/HaIf-Long pipes and five of these, including Muckle Jock’s and James Hall’s, had the fifth interval drone, the remaining nine or so having tenor, tenor, bass arrangements. Of the five in question, only one had the fifth interval drone in the baritone position, i.e., between the tenor and the bass, and this was a Robertson set from 1930. All of the other truly original Half-Long pipe drones had the fifth drone positioned and pitched at alto, sounding the fifth an octave above the baritone.

In other words, the Robertson set has the ‘Brien Boru’ pattern of drones and not the original Half-Long pattern. I can think of only one good reason for this which is that, as Charlton stated in the Border Magazine article, he wanted “volume”. The baritone drone being twice as large as the alto would obviously be a louder and more dominant contribution to the overall volume, but it is not traditional. Also, the general ‘colour’ of the sound is much more loud and brash, as the early Half-Long makers obviously realized. The alto drone, on the other hand, has a blending effect which compliments the harmonic structure of the bass drone (7).

In 1906 William 0’Douane, working with Henry Stark in London, produced and patented the ‘Brien Boru Pipes’ as a new Irish ‘Warpipe’ having three drones issuing from a common stock, arrayed as tenor, baritone, and bass, exactly as Robertson Half-Long pipes were to be produced a few years later. It is quite possible, if not likely, that Robertson, or those searching for pipes loud enough to use for marching Scout troops in Northumberland, saw these pipes and were impressed by the volume and therefore decided to adopt the Brien Boru pattern of drones for the new style Half-Long pipes. It may be interesting to note here that the Brien Boru pipes never really took the imagination of pipers in this country and had only limited success in Ireland, the two drone Scottish type Highland Pipe holding sway in that country. One of the reasons for its unpopularity was the difficulty in fingering the complex keyed chanter.

And so, where does this leave us? With no real answer to the riddle of the term ‘Half-Long’, one or two anomalies corrected, and, hopefully, some food for thought and some historical background. I think that it is important to take note of the original drone structure of these pipes; and it could be said that unless a set of pipes had this structure, then they are not true Half-Longs. In fact, they are only truly Half-Longs in the chanter also has a scale with the sharpened seventh.

With regard to nomenclature, I would like to finish with a list and description of the most popular pipes and what I feel should be their classification. I hope that discarding such terms as ‘Border Pipes’ is seen as constructive and that it helps us standardize the terminology.

Lowland Pipes and Northumbrian Half-Longs

Pipes characterized by a bag inflated by a bellows, having three simple drones issuing from a common stock and an open-ended chanter of conical bore construction. These pipes have the shrill nasal sound distinctive of outdoor pipes such as the Highland Pipe but are milder in volume. The chanter of these pipes may have either a sharpened on flattened seventh note. The drones may be arranged as either tenor-tenor-bass, tenor-baritone-bass, or alto-tenor-bass. Pipes having the sharpened seventh and the alto-tenor-bass drone configuration are the true Northumbrian Half-Longs. The usual pitch for this class of pipes is B-flat.

53

Scottish and Northumbrian Smallpipes

Pipes characterized by a bag inflated by a bellows having three or more drones issuing from a common stock. The chanters of these pipes are of cylindrical bore construction and have a characteristically mellow ‘indoor’ sound. These pipes are available in most pitches. The Scottish Small-pipe drones are usually in the standard ‘Scottish’ format of tenor-tenor-bass although they can be obtained in tenor-baritone-bass configuration. It is usual for them to have three, but they can gave up to five drones. Scottish smallpipe chanters are open-ended and are played as Lowland/Highland/Half-Long pipes, and can also have the sharpened seventh. Keys can be fitted to extend the range above the octave, below the subtonic, and between notes to give semitones.

Northumbrian pipe chanters are a closed chanter, are usually pitched in ‘F’ or ‘G’ (sometimes ‘c’ or ‘D’), and can have from zero to seventeen keys. Fingering is of the ‘closed’ type. Drones on keyless sets are three in number, but for keyed sets will have four or more. The ‘standard’ sets have seven keys and four drones.

Parlour Pipes, Reel Pipes, Chamber Pipes and Shuttle Pipes

All less popular variants of the above categories, Irish Uillean and Highland pipes.

No doubt there will be further disagreement with some aspects of this article, but I think that you will find that the descriptions of the pipes mentioned are historically correct, and that my nomenclature does not further confuse the situation.

References Cited

1) William H. Grattan Flood, The Story of the Bagpipe, Walter Scott Publishing Co., London, 1911.

2) Roderick D. Cannon, The Highland Bagpipe and its Music, John Donald Publishers, Ltd., Edinburgh, 1988.

3) William A. Cocks, in his 1933 book, The Northumbrian Bagpipes, Their Development and Makers, refers to the Half-Longs as the Northumbrian Large Pipes and elsewhere as the Hill Pipes.

4) Mr. James Hall was Piper to three successive Dukes of Northumberland, from 1892-1931. He died in 1942 at the age of 86. His Half-Long pipes were gifted to the Museums Service in 1923 by G. W. Hedgely. Together with the ‘Muckle Jock’ pipes, they were the model for the new generation of Half-Longs.

5) Probably made by Robertson of Edinburgh.

6) Historical information supplied by Colin Ross, pipemaker, of Whitley Bay.

7) Technical information supplied by Colin Ross.

54

THE MANY SETTINGS OF MAGGIE LAUDER By Brian E. McCandless

To bring some historical and anecdotal continuity to the Lowland music we play, I’d like to use the example of Maggie lauder, a comical song written around 1645 by Francis Semple (also spelled Sempill), of the town of Beltrees in Renfrew County, Scotland. Judging by its appearance in numerous song and instrumental collections, one could conclude that it has been a hit for over 300 years! It is of special interest to us as Lowland pipers in that Semple’s words recount the interchange between a piper named ‘Rob, the Ranter’ (a Border piper?) and Maggie Lauder. No doubt, the words which have come down are not original, nor are the only, as attested to in The Garland of Scotia. edited by John Turnbull and Patrick Buchan in 1841. They wrote: “This curious song is very old. Tradition ascribes it to Francis Semple, the author of The Blythesome Bridal. We possess a much more graphic version in manuscript, rich as this one is in allegory, but we We’ll not pollute our pages by giving it here. Pity it is that our wittiest songs have thus brought upon themselves their own condemnation.” The ‘allegorical’ lyrics which they presented, and indeed, those which have been republished many times follow:

MAGGY LAUDER

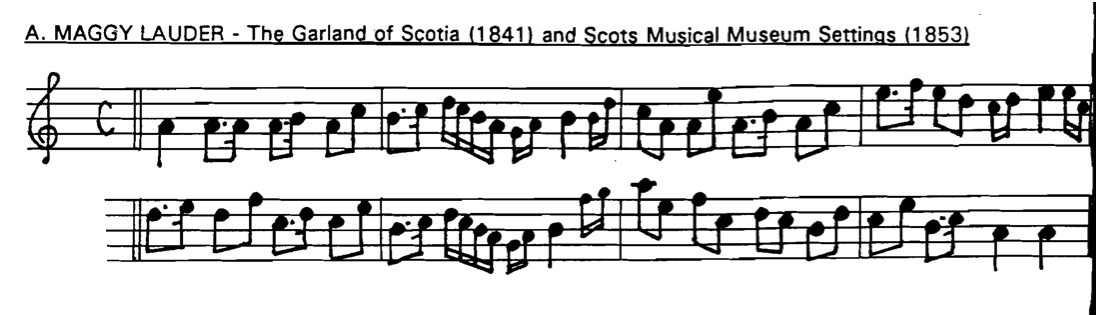

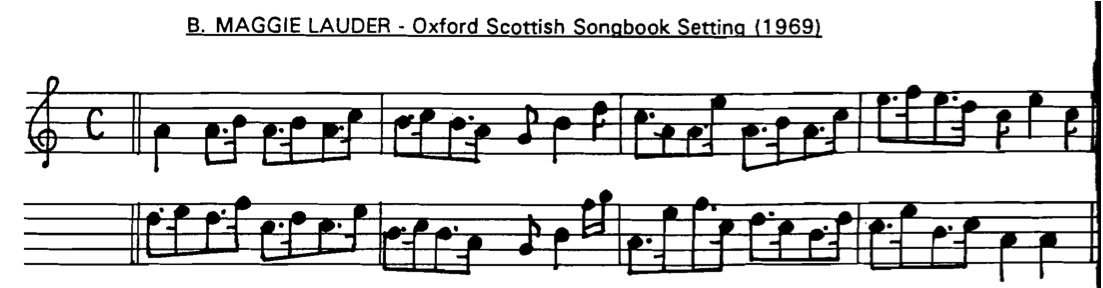

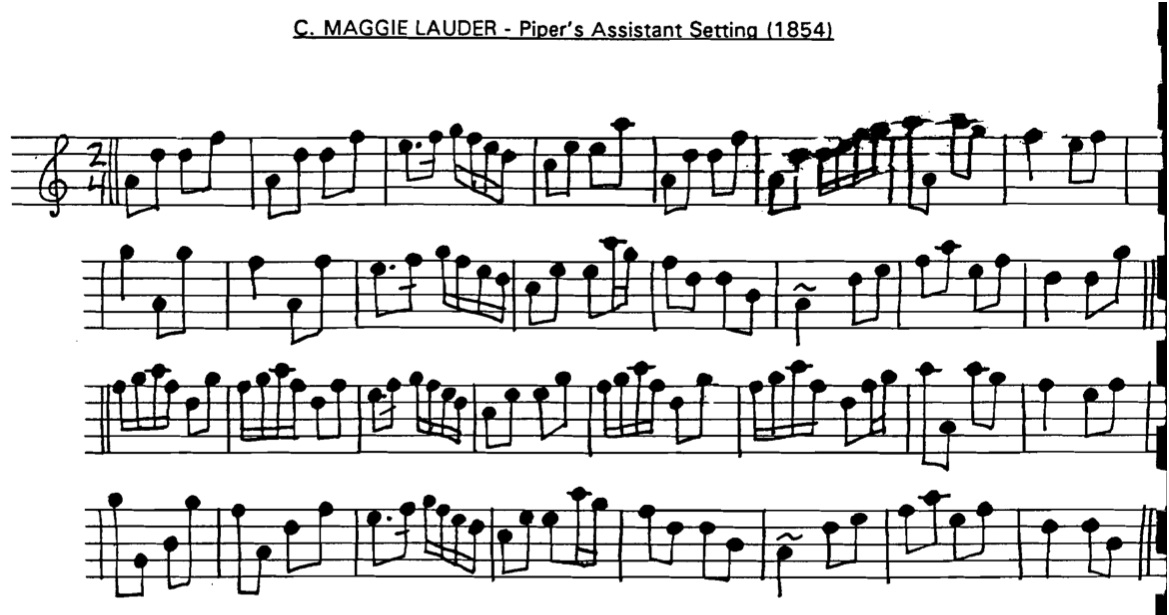

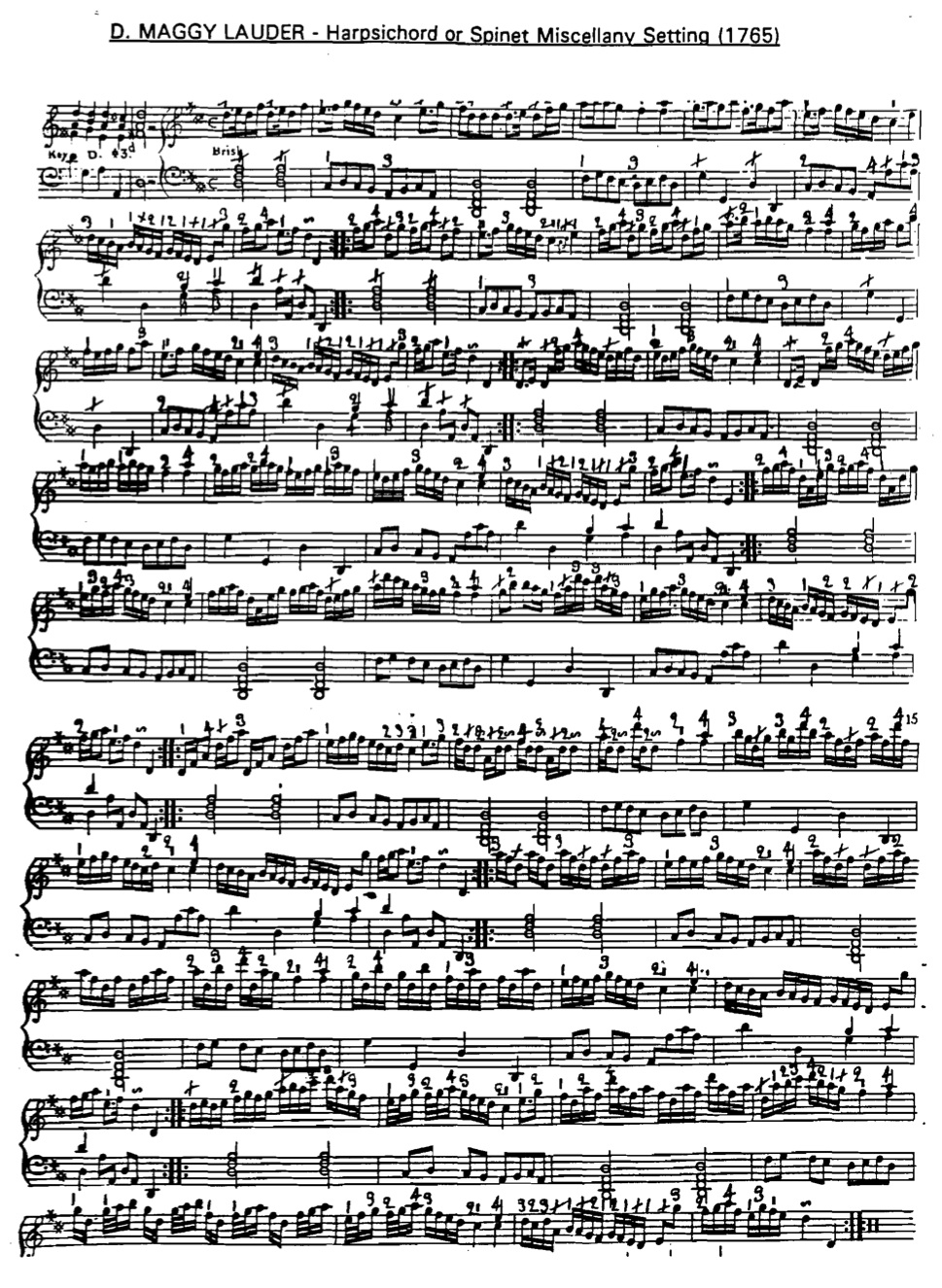

According to William Stenhouse’s notes to James Johnson’s 1853 Scots Musical Museum, quoting William Tennant (circa 1838), “In former times, the singers of this ditty used to inform their audience that Maggie was at last burnt for a witch; I could never find her name in any lists of Satan’s Seraglio which I have had the opportunity of inspecting.” Several melodies have been assigned to the song, and one of those was also set to the words of ‘The Joyful Widower’! Setting A below is found in both The Garland of Scotia (1841) and the Scots Musical Museum (1853). A slight variation of this melody B is found in the more recent Oxford Scottish Songbook (19691. Setting C is a completely different melody with the same name, published in The Piper’s Assistant (1854). Finally, and most impressive, is setting D, with multiple variations, found in Robert Bremner’s Harpsichord or Spinet Miscellany (1765). The melody line of this version seems to contain elements common to setting C, and with all its arpeggio runs, is reminiscent of ‘traditional’ Lowland and Northumbrian instrumental music (look, for example, at the settings for ‘All the Night I Lay With Jockey’.

55

56

57

GORDON MOONEY – A PROFILE by Brian McCandless

Nowadays, the name of Gordon Mooney is synonymous with Lowland and Border piping, for he has been instrumental in the revival of the traditional repertoire and art form peculiar to the Lowland and Border bagpipes. He is a founder and former Chairman of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society, he has released three recordings with Lowland pipes and Scottish smallpipes, he has written a tutor for the Lowland pipes, and he has collected and arranged a notable body of traditional Lowland music for the pipes, some of it known to have been performed on pipes, some of it deserving to be played on the pipes. Born in Edinburgh in 1951, by 1958 he was already studying Highland bagpipes under Pipe Major Hance Gates of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band. His interest in the bellows pipes of Scotland would appear to have been sparked by his exposure to a session of Northumbrian pipers playing at the Newcastleton Folk Festival in 1976, not an unpleasant way to fall into the small-piping world. He had already played a bit of Highland pipes, and shortly after that festival he acquired a set of Northumbrian pipes. He joined the Muirhead Pipe Band in the late 1970s and met fellow band members Rab Wallace and Jimmy Anderson who were (and are) Scottish bellows pipe players in folk music bands.

The difficulty in procuring a set of Lowland pipes caused Gordon. study a bit of wood working so that he could build a set from plans he had found (in Cock’s and Bryan’s book on Northumbrian pipes, as I recall). As began playing these more and more, it became apparent that many of the old traditional Northumbrian tunes he had learned on his Northumbrian pipes couId be played on the Lowland pipe chanter, occasionally requiring an additional note above which Gordon achieved by adding a “high-B” key to his chanter. He undertook an intense interest in this aspect of his piping – that is, in researching old Lowland tunes which could be played the Lowland pipe. By the early 1980’s, he had built up a significant number of tunes, which Ied him in 1982 to publish Volume I of A Collection of the Choicest Scots Tunes for the Lowland and Border Bagpipe. Volume II followed in 1983, and now, both collections have been consolidated into one volume. It was during this period that the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society was founded. By 1985 Gordon had written a tutor (with yet more tunes in it) for the Lowland bagpipes in what was a bold step for the otherwise shy and reserved man from (then) Linlithgow. Two cassettes also emerged from the Saydisc label, “The Border Reiver”, with strictly Border pipes and Scottish smallpipes, and “? in the Tail”, with arranged Scottish and Northumbrian music played by ‘B and the Drones’. Thus in just a few years, Gordon had pulled together the elements necessary for the revival of an historically defunct instrument – he had made an instrument, collected the music, wrote a tutor, and recorded his interpretation of the music.

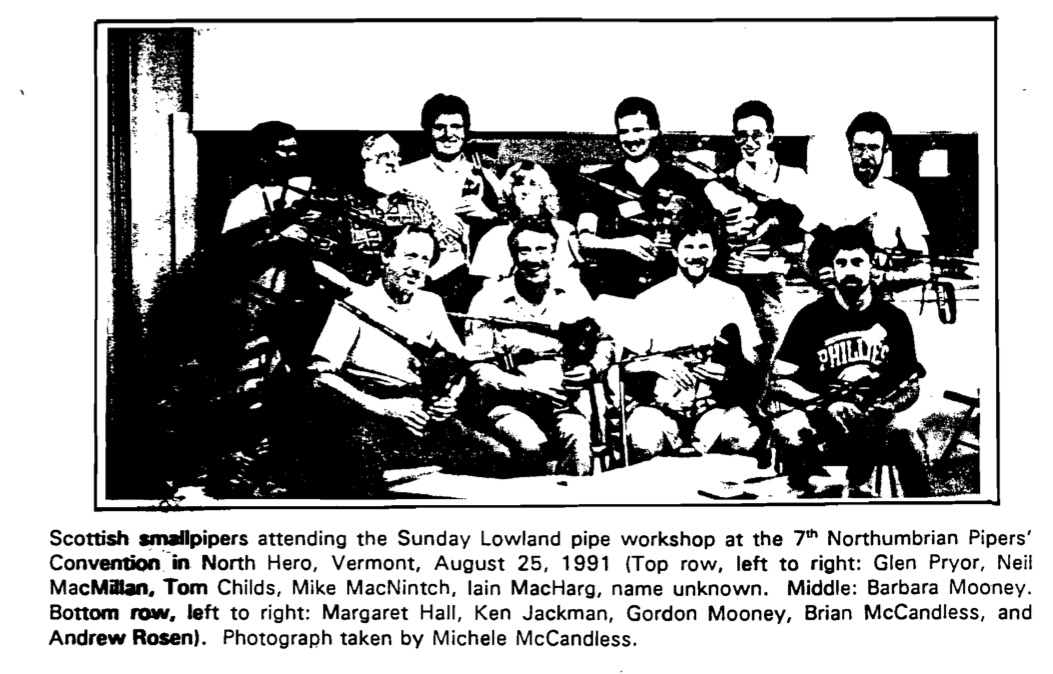

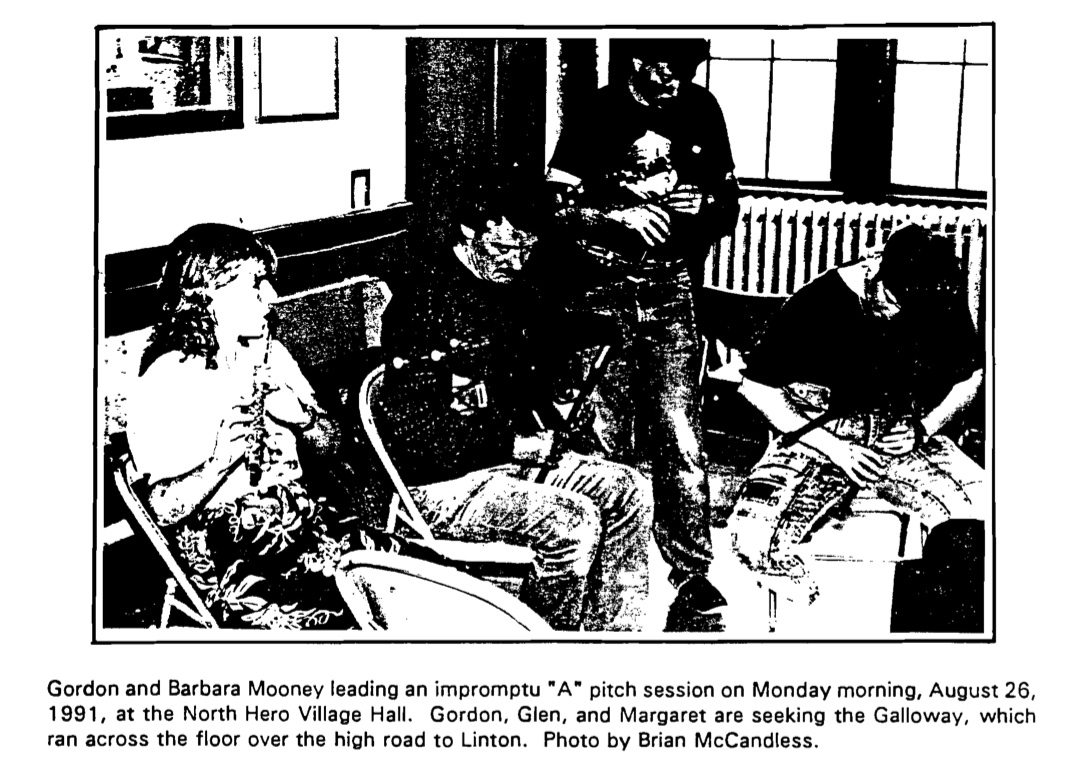

During this period of the mid·1980’s, North American pipers began seeking out Gordon, desperate for copies of his books and tapes and curious about “the man with the tunes”. He did much to promote Lowland piping within the North American piping community by attending the 1990 and 1991 Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention in Vermont where he spoke on the history of Lowland pipes and demonstrated various aspects of his Lowland pipe style and technique. He is pictured on the facing page playing at North Hero in 1990 (Sketch by W. Richmond Johnston).

In 1989 he released an album, “0’er the Border”, along with his wife, Barbara, Nigel Richard, Jo Miller, Dougie Pincock, Alan Reid, Brian Miller, and Charlie Soane. The album is an effective and evocative interpretation of Lowland Scottish music, built around the music of the Border region of Scotland. More recently, in Jedburgh, he co-organized an exhibit of Lowland bagpipes and a Collogue of Lowland pipers, and this year he began a Traditional Music mail order company specializing in piping music and literature. We look forward to more of Gordon’s music and words as he returns this year to North Hero.

58

59

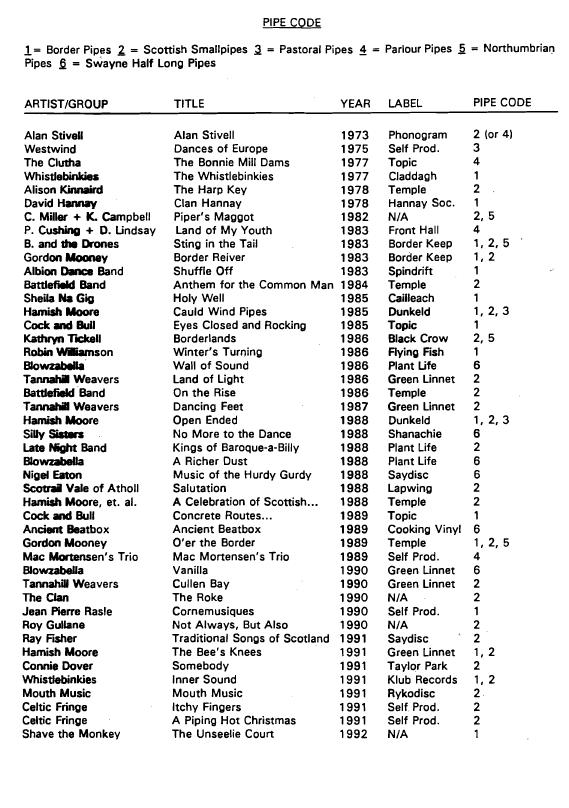

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Mike MacNintch

To keep this discography completely up to date is nearly impossible because new recordings are becoming available constantly. Therefore, we endeavor to keep it up as best we can. Of course there are more recordings than we have listed here.

Robin Williamson, the accomplished harper, fiddler, and whistle player also plays the Scottish smallpipes and the Border pipes. Although we only have information on one of his recordings with pipes, he did use Border pipes on the soundtrack to the movie “Willow”

The Whistlebinkies feature the Border pipes on all of their albums. and Scottish smallpipes on two. It is said that Rab Wallace, their extraordinary piper, prefers to use the Border pipes because they are not as overpowering to the other instruments as the Highland pipes. Again, unfortunately, we only have the details of two of their recordings; there are several more and alI are highly recommended.

The first entry in the list may cause considerable interest, for AIan Stivell performs “She Moved Through the Fair” on the album, along with vocals, harp, percussion and pipes. The pipes are either the Scottish smallpipes or the parlour pipes. It is hard to say, but the work is certainly beautiful.

Previously we had included·A Controversy of Pipers” on the list. This is a fantastic Highland piping album, but alas, no Lowland pipes are featured. However, several of the players are well known to be players of Lowland and other bagpipes. A good listen to this recording will do no harm to anyone.

There are two videotapes available with spots of smallpiping on them. One is the “Scotrail Vale of Atholl Pipe Band, Live in Concert, Ballymena, Northern Ireland”. There are two performances by the Vale’s smallpipe quarter. Great stuff! The other tape is one of Highland playing in various locations in Scotland. There is apparently a performance by one of them on the smallpipes.

Not all of the albums listed offer music of the border regions. Some are distinctly Highland in flavor while others are very European. Keep an open mind toward these different influences, as they may rub off onto your fingers, and lead you to new ground.

Concerning the subject of keeping an open mind, there are a great many recordings which do not feature Lowland Border pipes, but could be of related interest. In particular, Northumbrian and Uilleann piping are generally interesting to players of Lowland pipes. Both have traditions that overlap and the instruments are most certainly inter-related. There are literally scores of these recordings available, and we feel that we should try keep our list focused on the Lowland plpes

IF YOU HAVE information which might be useful to us, or suggestions 8nd comments, please send them to the Editor. Our humble apologies for any inaccuracies:

60

61

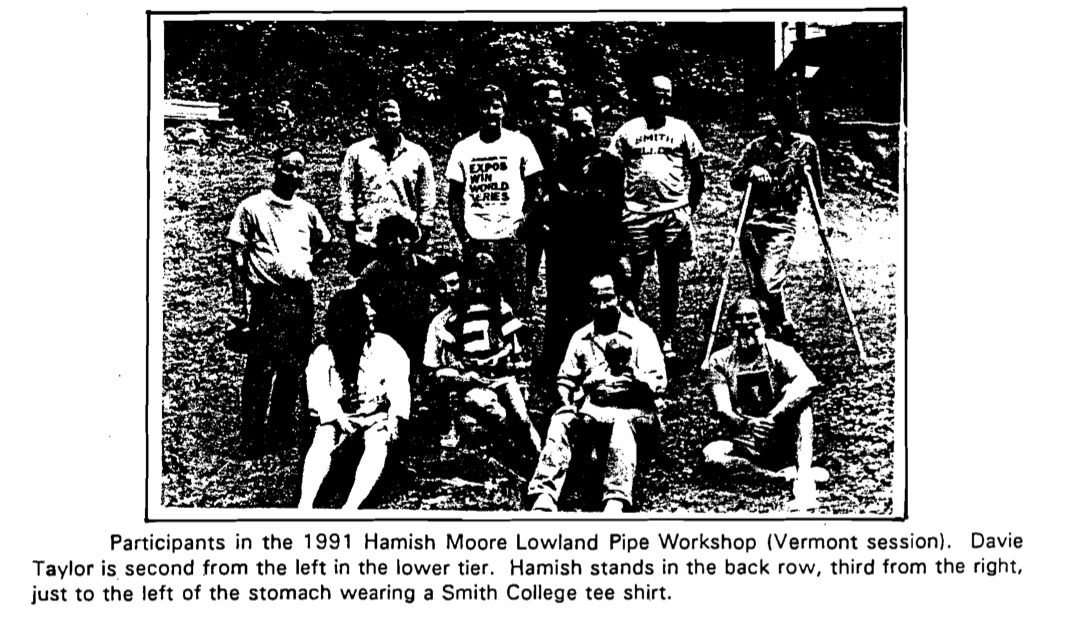

HAMISH MOORE LOWLAND PIPE WORKSHOP, 1991: A REVIEW by Steve Bliven

My wife just gave me that look when I suggested that I’d like to go to a week-long bagpipe workshop. Sure, she remembered Hamish Moore from the set he had played at North Hero two years before. “But bagpipe camp?”, and she wandered off muttering something that sounded like “mental case”, but I took to mean “more power to you.” (Later she finally got into the spirit and offered to sew name tags onto everything I was taking – including my bellows and bag,)

But I figured that a week with a well-known piper and pipe-maker was just what my fledgling career needed. I’d bought a set of MacHarg pipes at North Hero the year before and, with help from Tom Childs, had reached a certain level of comfort – and a week-long camp was just what I needed to make the jump to the next level. Besides a week in rural Vermont in late July would be a welcome respite from work and household chores. I did have some anxiety wondering if I would be too much of a beginner to get any benefit, or if I would just embarrass myself by slowing up the group – but a nice letter from Matt Buckley, host for the camp, reassured me that he had personally seen Hamish spend extra time with beginners and that I shouldn’t worry about it, So I signed up. And subsequently was very glad I did…

I arrived at Matt’s house located off a dirt road in the woods on Sunday night and noticed that several other campers had already arrived and set up their tents in the yard. (Matt offers free camping space and use of his kitchen, but I stayed in a nearby bed and breakfast.) At supper at the local pizzeria, I met Hamish and a second instructor, Davie Taylor, as well as most at the other campers. By the second pizza and third beer any newness had worn off and we were well on the way to becoming friends.

The group came from mixed musical and piping backgrounds. Half of the ten members fell into the beginners group (with two in the “never touched one before” category). most of the rest classifying themselves as advanced. Only half of the group (including some of the lowland pipe beginners) had experience on highland pipes. Virtually all had some prior musical background, all on “folk” instruments, and half were repeaters at a Hamish enclave (some had attended multiple sessions).

I quickly proved that I deserved my beginners ranking and was assigned, with four others, to Davie Taylor while the more advanced students went off with Hamish. Davie proved to be an ideal instructor for the beginners; patient, yet demanding at the same time, he pushed us further than any of us expected to go over the course of the week. His credentials were certainly in order – he is the teacher to whom Hamish sends his offspring. His presence also made possible the individual attention that was so beneficial. Apparently the year before, Hamish had attempted to instruct all levels of the entire group by himself, thereby spreading himself pretty thin. But this year it certainly worked. Each of the beginners worked with a goose – no need for tuning of drones – and all in the key of A. This simplified the process and allowed the formation of smaller groups for practice. The advanced group used their own pipes in a common key. Later in the week, the instructors switched off for a couple of sessions providing the beginners with several lessons directly from Hamish.

The day broke down into a routine of two hour sessions with the instructors in the morning and afternoon working on repertoire, techniques, and style; even in the beginners group there was a strong emphasis on the latter. Many readers are familiar with Hamish’s music through his recordings or performances and his non-traditional form is apparent – a recent article in Dirty Linen (a US publication “dedicated to folk, electric folk, traditional and world music”) refers to piping’s so-called ‘hooligan’ element, as personified by Hamish Moore and Gordon Duncan, whose exploits are either hair- or hackle-raising depending on your viewpoint.” Consequently, I was surprised at the emphasis on and amount of respect paid to the traditional styles. Hamish repeatedly stressed that his piping developed out of the traditional forms and that his “rebellion” was against the overly structured methods taught in the regiments. He insisted on finding the music in the tune, not merely replicating the technique.

62

“Let the music swing” was heard many times.

Each afternoon ended with a session on the history and legends of Scotland or piping, instrument set-up and maintenance, or a critique of recordings of pipe music. Several evenings were spent in Burlington at sessions with local musicians over fermented beverages.

Despite all the activity, there was still time to get individual instruction, play together in small groups or privately run through the day’s lessons, swim, talk, or just sit back and enjoy the sounds of the country.