To download the original scanned Journal as a pdf please click here.

JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 6 September 1993

JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION

OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 6 SEPTEMBER 1993

CONTENTS

FOR YOUR INFORMATION 5

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 8

CALENDAR 14

WELCOME TO THE N. A. A. L. B. P. and Bellows Piping 15

by Brian McCandless

CARE AND MAINTENANCE OF BELLOWS-BLOWN BAGPIPES 28

by Michael MacHarg

A BORING ARTICLE

by Eoghan Ballard 30

ACOUSTICAL ASPECTS OF BAGPIPE CHANTERS 34

by Brian McCandless

INTERVIEW WITH RIK PALIERI – PLAYER OF POLISH PIPES 38

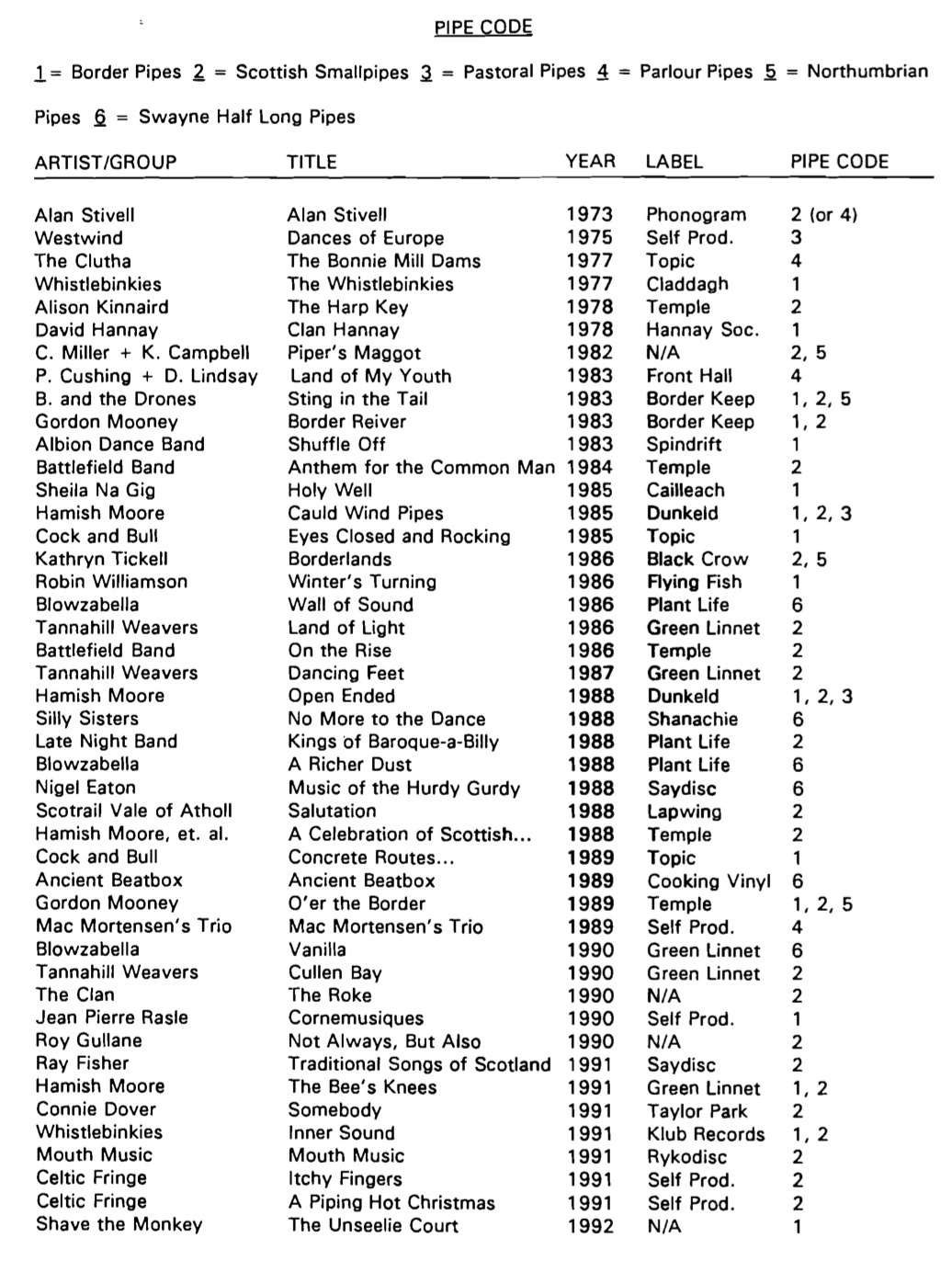

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY 46

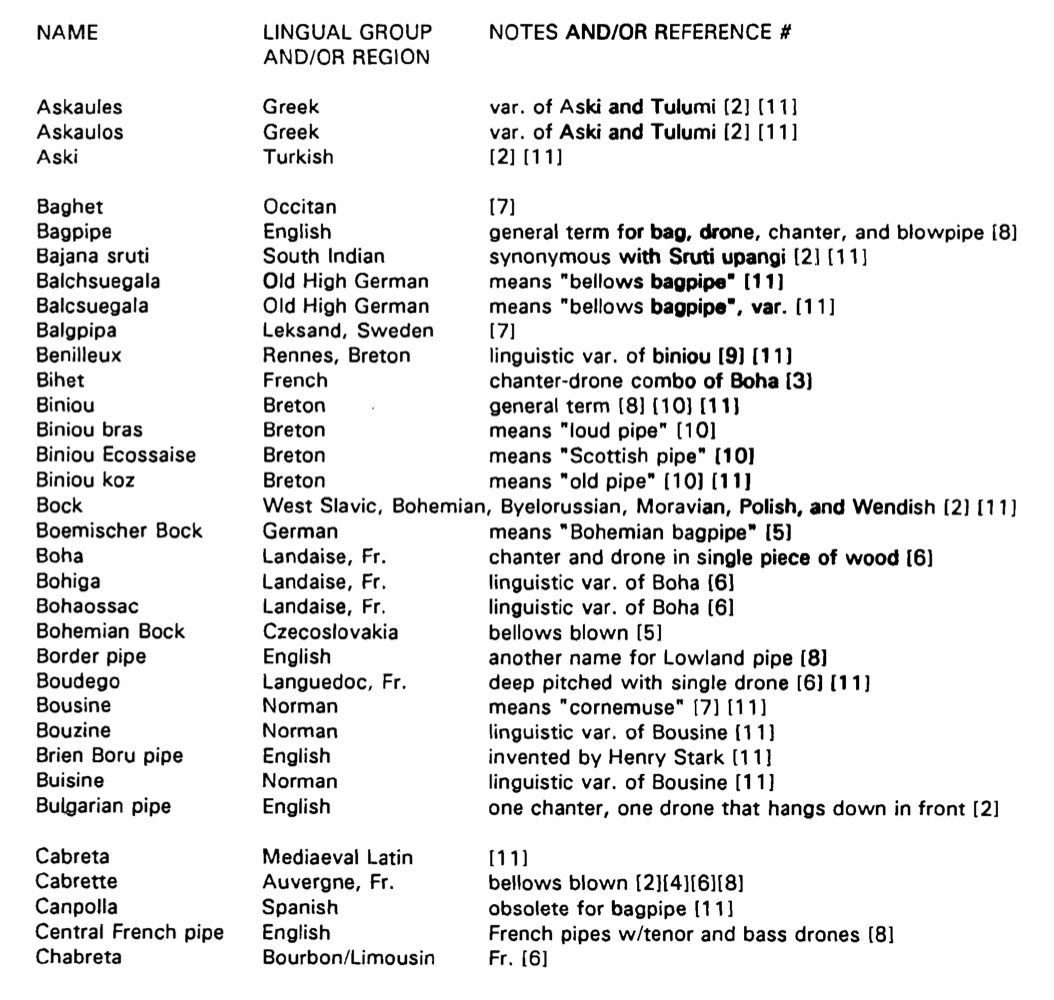

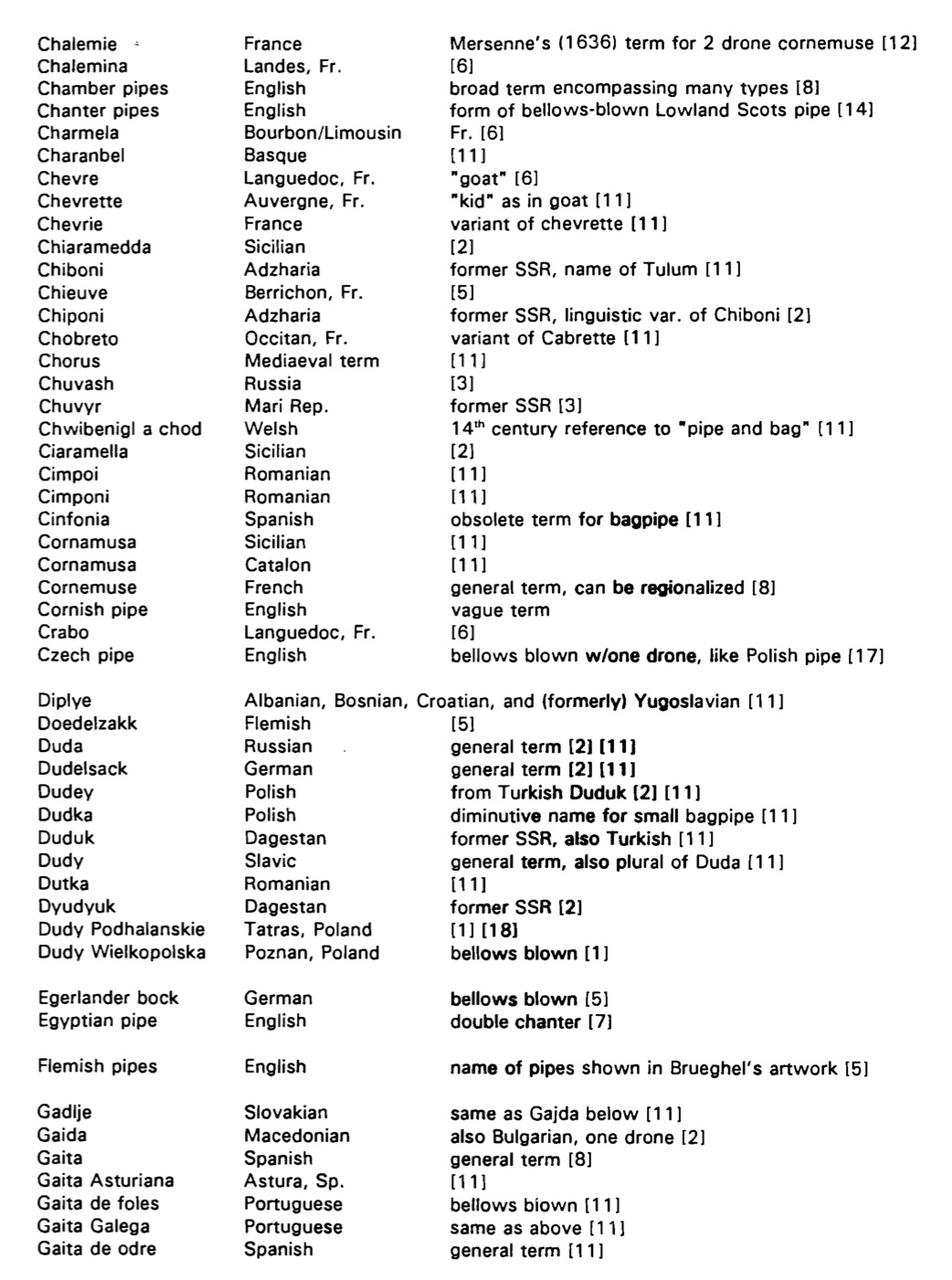

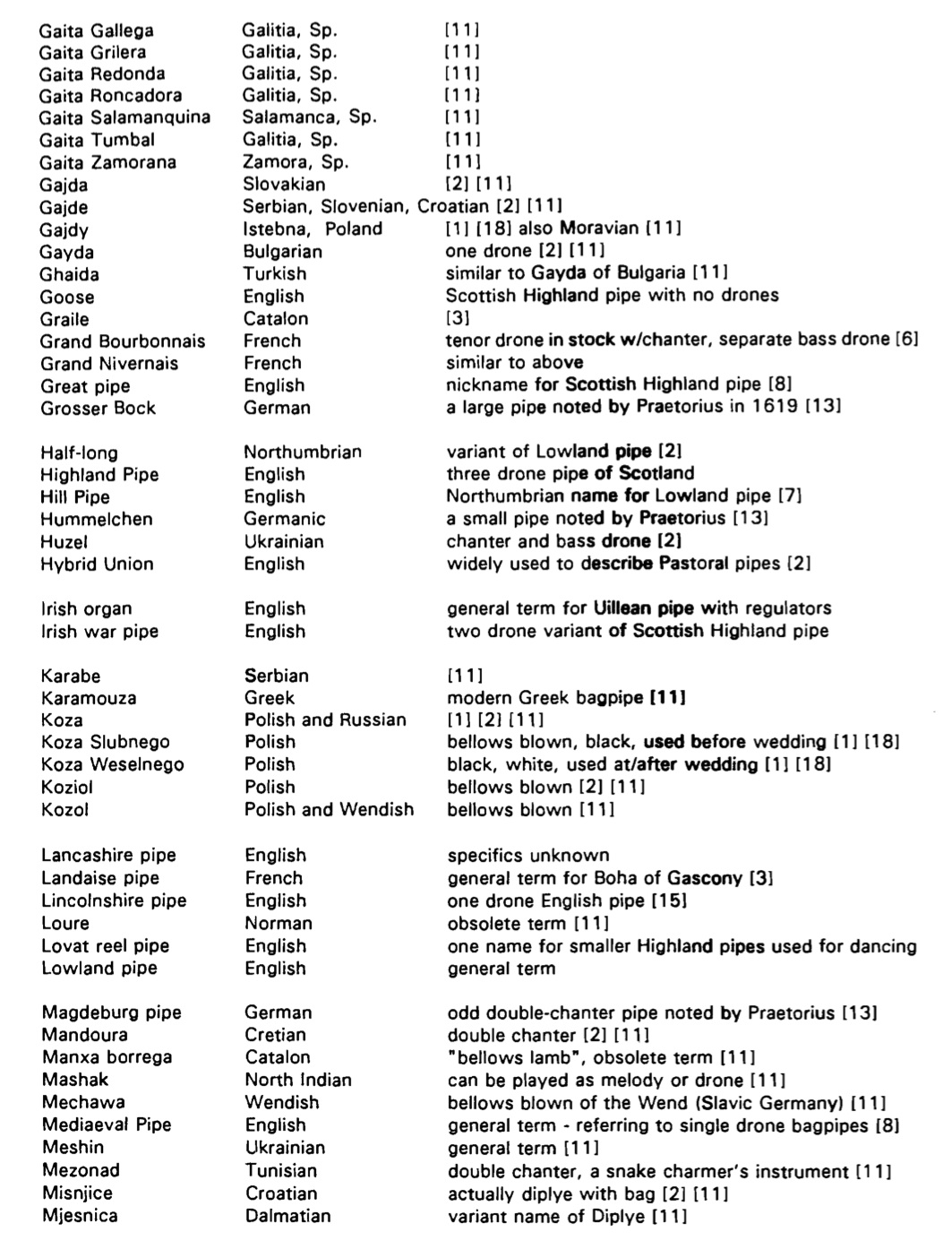

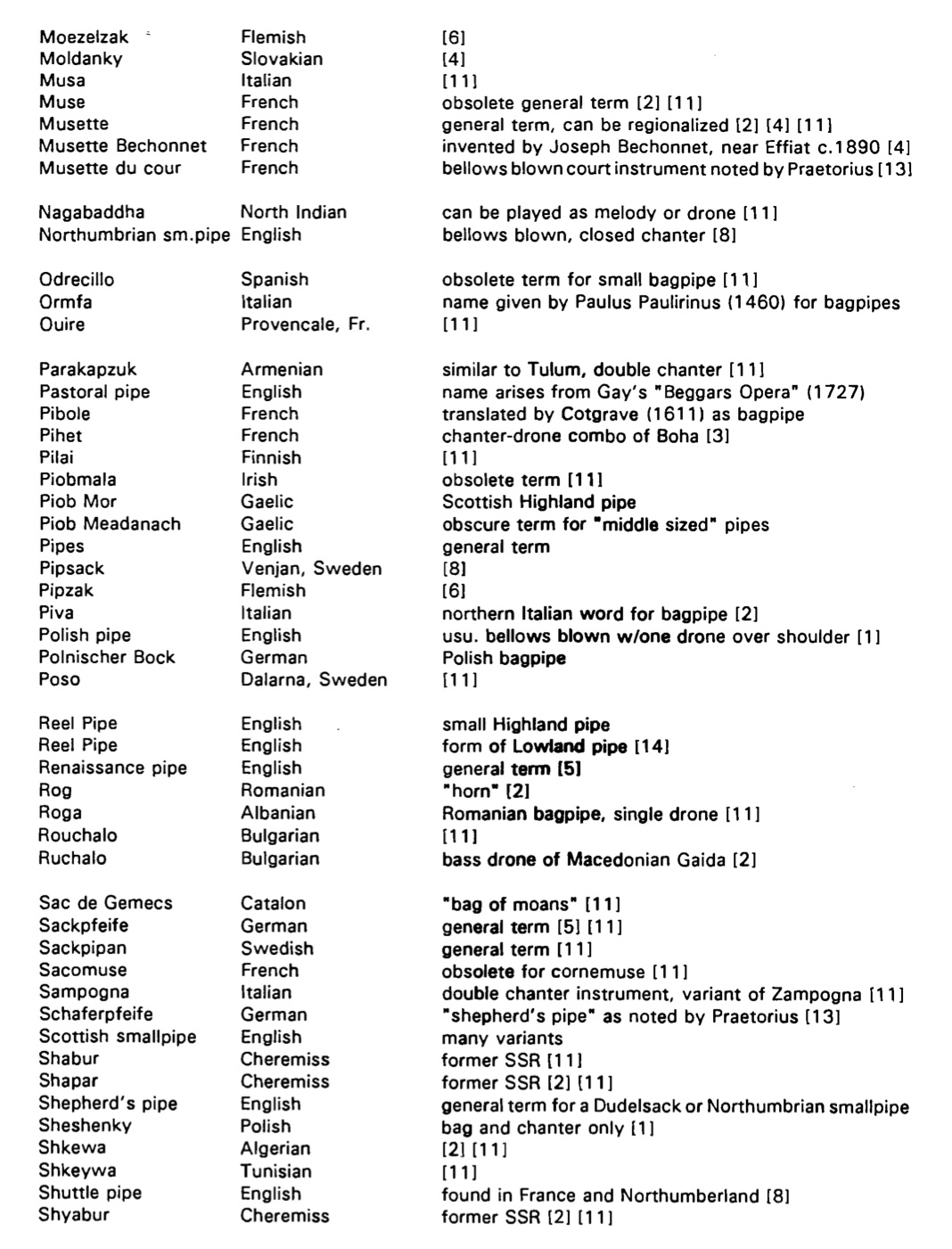

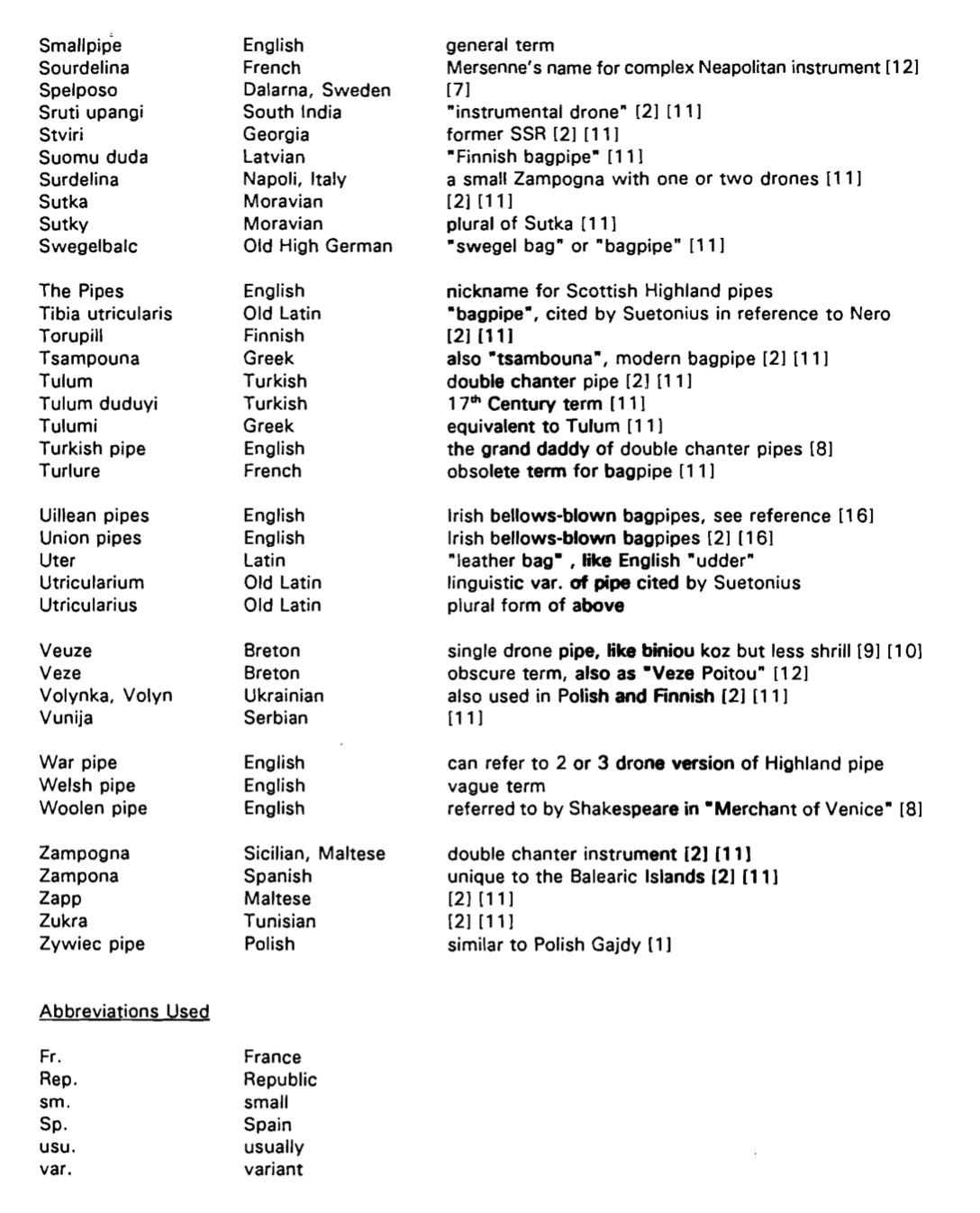

BAGPIPE NAMES – A VERY LONG LIST 48

N.A.A.L.B.P. MEMBERS – ALSO A LONG LIST 54

ADVERTISEMENTS 58

1

2

Group photo of the attendees at the 1993 Piper’s Day in Elkton, Maryland (photo by Michele McCandless).

Thank you to all who came and helped make this event a success!

3

4

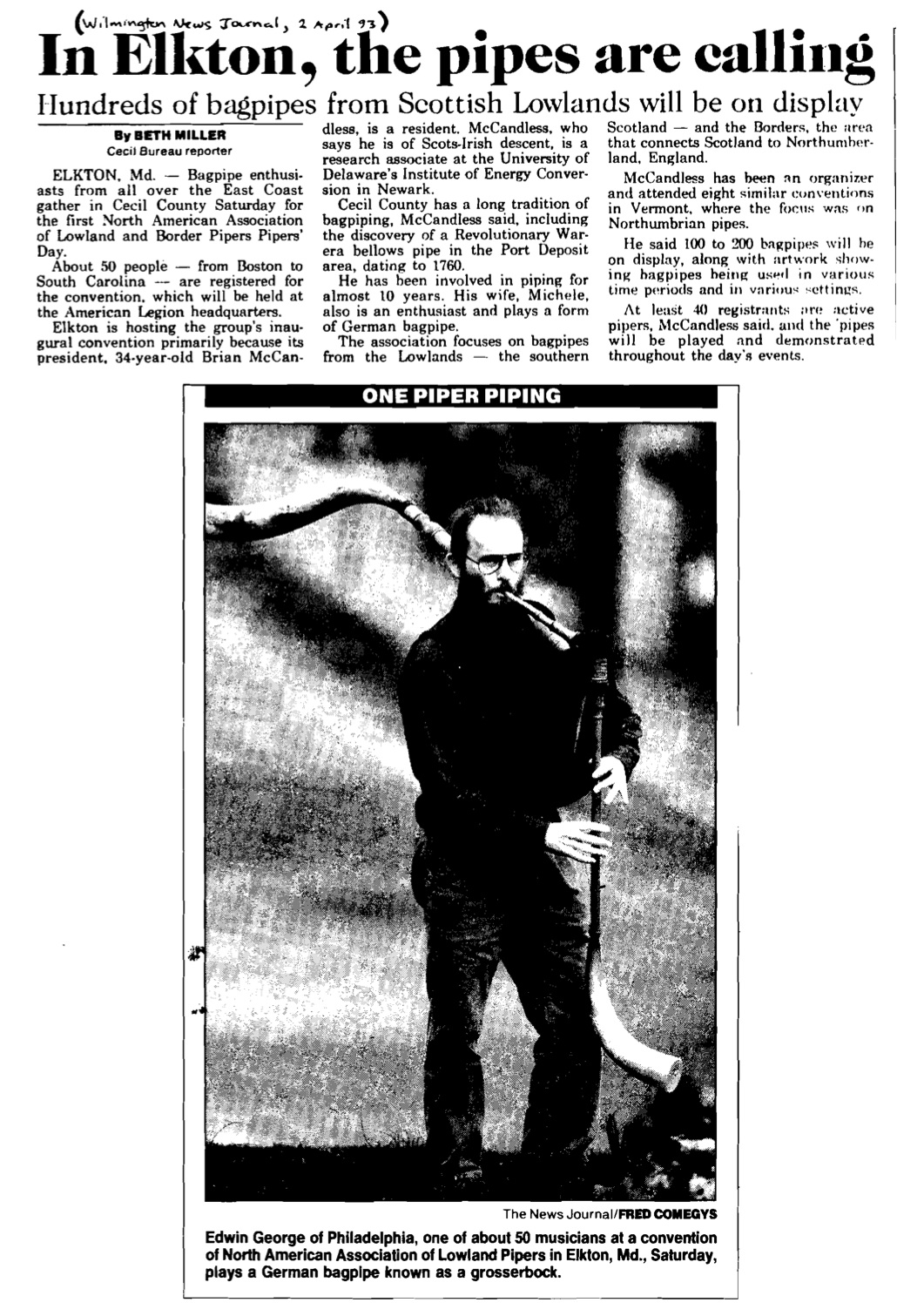

FOR YOUR INFORMATION 1993 N.A.A.L.B.P. Pipers’ Day

The first ever N.A.A.L.B.P. Pipers’ Day was held on April 3, 1993 in Elkton, Maryland. Approximately 40 pipers pre-registered for the event which included a bagpipe exhibition, impromptu demonstrations, dinner, a concert, and a dance. The staff of the American Legion Hall provided a relaxed atmosphere for us to hold our modest event. The early part of the day was taken up with people looking over each others pipes and demonstrating instruments for one another. Michele McCandless organized an informal percussion workshop for about ten people. Karen Meyers and Alan Fendler played hurdy gurdy duets in the foyer throughout the afternoon. Some interesting instrument combinations were demonstrated, notably bombarde and biniou (Brad Angus and Mike Rackers), Uilleann pipe and Scottish smallpipe (Nick Whitmer and Burt Mitchell), hurdy gurdy and grosserbock (Karen Meyers and Edwin George), and cornemuse and musette Bechonnet (Mike MacNintch and Brian McCandless). The evening concert kicked off with Pan’s Fancy (Karen and Edwin) followed by Chip Reardon on Parlor pipes, Glenn Pryor on Scottish smallpipes, Sam Grier on Pastoral pipes, Eoghan Ballard on Uillean pipes, Rick O’Shea on Uillean pipes, Brad Angus on Uillean pipes, Burt Mitchell and Nick Whitmer on Scottish smallpipes and Uillean pipes, Mike Rackers on Highland pipe and Dan Emery on Highland pipe. From 8:30 until 10:00 Pam Goffinet led dances from Brittany, France, Germany, England, and Scotland. Music was provided by Dave Cottrell on melodeon and guitar, Jon Kmetz on viola, Mike MacNintch on cornemuse, Brian McCandless on musette Bechonnet, Michele McCandless on guitar and drum, and Don Shaffer on fiddle. Afterwards, a session was held at the McCandless home two blocks down the street. The N.A.A.L.B.P. is tentatively planning to hold a second event this coming April 1-3.

Ninth Northumbrian Pipers Convention. 1993

Once again, Alan Jones put together a successful convention in Vermont with an all star cast of pipers from everywhere! This is the second year that the event was held in conjunction with the N.A.A.L.B.P. To list some of the personalities involved in this event: Richard Butler, Mike Dow, Frank Edgley, Sam Grier, Paddy Keenan, Michael MacHarg, Mike MacNintch, Jean-Christophe Maillard, Brian McCandless, Hamish Moore, Sean Folsom, Chris Ormston, Jerry O’Sullivan, Rik Palieri, Gille Plante, AI Purcell, Lance Robson, Colin Ross, Ray Sloan, and so many more! There were workshops held on every possible piping topic, from reed making and pipe maintenance through French music and tutelage on Northumbrian and Scottish smallpipes. Sean Folsom and Rik Palieri held an extraordinary demonstration of bagpipes from western and eastern Europe including a duet on the Polish pipes. Irish music was nearly continuous all weekend, beginning in the lounge at Shore Acres Inn on Friday night, through to the Town Hall kitchen late Sunday night. A four hour dance was held on Saturday night split between Contra, Quebecois, and Breton. An equally long concert was held on Sunday night starting with two young lads from the Black Watch and finishing up with Paddy Keenan. The next convention is tentatively scheduled for August 27-29, 1994. For more information contact Alan Jones.

5

Quotation

The following was sent in by Stuart Mowbray, taken from lord Chesterfield’s letters to his son (18th century):

“As you are now in a musical country, where singing, fiddling, and piping, are not only common topics of conversation, but almost the principal objects of attention, I cannot help cautioning you against giving in to those (I will call them illiberal) pleasures (though music is commonly reckoned one of the liberal arts) to the degree that most of your countrymen do, when they travel in Italy. If you love music, hear it; go to operas, concerts, and pay fiddlers to play to you; but I insist upon your neither piping nor fiddling yourself. It puts a gentleman in a very frivolous, contemptible light; brings him into a great deal of bad company; and takes up a great deal of time, which might be better employed. Few things would mortify me more, than to see you bearing part in a concert with a fiddle under your chin, or a pipe in your mouth.”

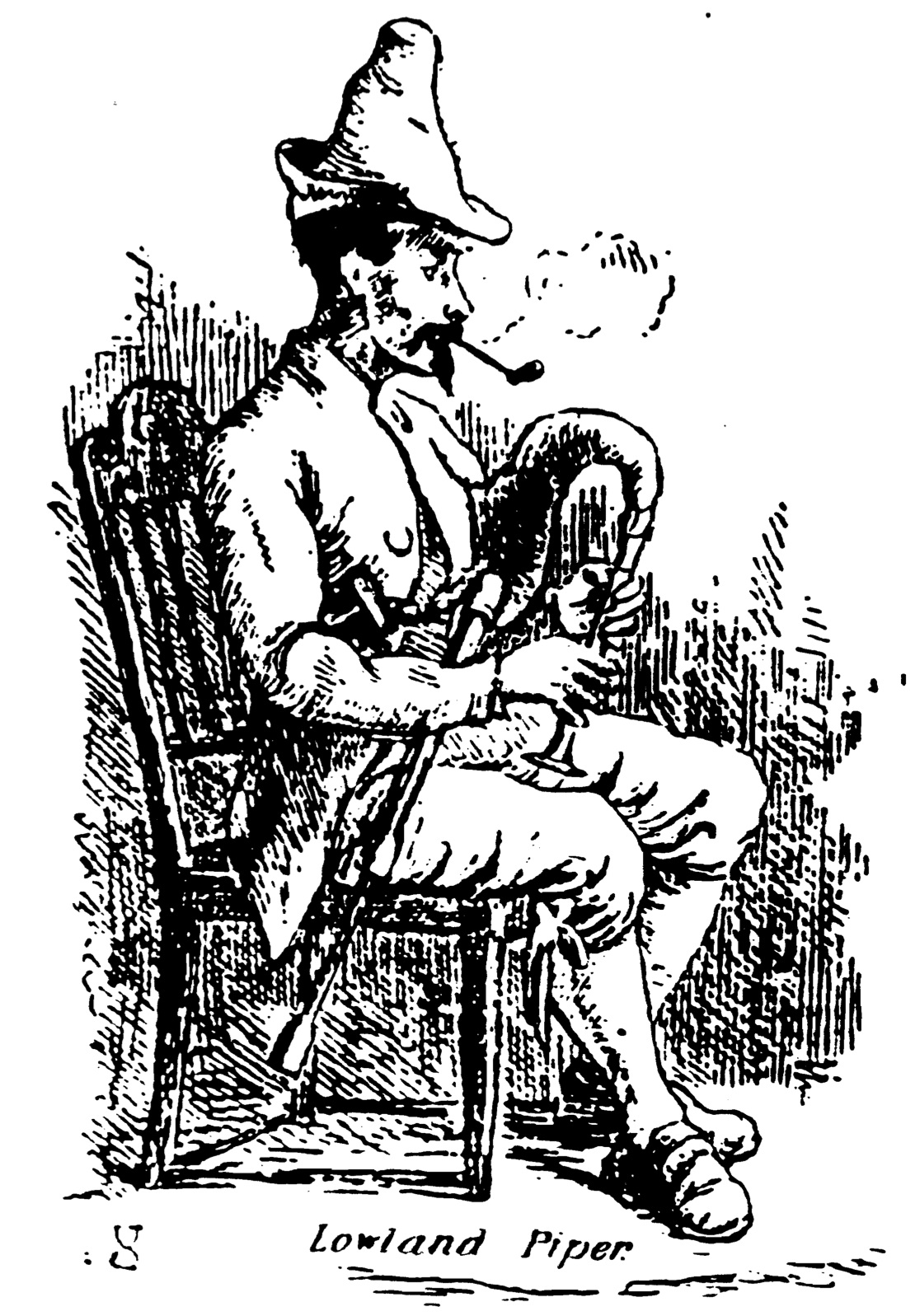

Lowland Piping Anecdote

This was sent in by Eoghan Ballard, who found it in The Supernatural Highlands by Francis Thompson, Robert Hale and Company, London, 1976.

“The ring dance was the common dance at the kirn, or feast of cutting down the grain, and was always danced…by the reapers on that farm where the harvest was first finished. On these occasions they danced on an eminence, in the view of the reapers in their vicinity, to the music of the lowland bagpipe, commencing the dance with three loud shouts of triumph, and thrice throwing up their hooks in the air. The intervals of labour during Harvest were often occupied in dancing the Ring to the music of the piper who formerly attended the reapers. This dance is still retained among the Scottish Highlanders, who frequently dance the Ring in open fields when they visit the south of Scotland as reapers, during the autumnal months.”

Early Scottish Smallpipes in Collection

James Coldren sent in a page from The North American Scotsman dated August 1970, containing the following details of the transfer of a bagpipe collection from Mr. Torquil Macleod, of Borreaig, Tain to the Inverness Museum:

“The collection ranges from rare 17th and 18th century miniatures to a pair made by Mr. Macleod’s father, Mr. Donald Macleod in 1908, when they had been made for the artisan section of the Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh, and Mr. Macleod (senior) had been awarded a gold medal. The set, valued at 1000 pounds, is probably the only one of its kind in existence. It is mounted in gold with an engraved Scots thistle motif. Other pipes in the collection include an 18th century miniature chamber pipe; and 18th century bellows pipe bearing part of the crest of the Cromartie family; a rare 18th century great Highland bagpipe; a 19th century miniature set; a 17th century bellows pipe mounted in brass and staghorn; and a rare 18th century miniature set. There are also a number of 17th century pipe reeds and three pictures.”

If anyone knows more about this collection, please send your information to the editor so that we can follow up on these tantalizing instruments.

6

E-Mail for Bagpipes

For pipers with computer access to the internet, a ‘bulletin board’ of bagpipe descriptions and experiences has been on-going under the “bagpipe” forum (to subscribe send your e-mail address and a request to: pipes request@sunapee.dartmouth.edu and to send a message use: bagpipes@cs.dartmouth.edu). A few members of N.A.A.L.B.P. already participate in this forum, and it can be foreseen that one day soon e-mail correspondence will supersede printed media in timeliness and access to information. If you have access to a computer with a modem, then you should get on this valuable resource. Recent topics of correspondence have included bellows techniques, bag tying, reed making, and overall bagpipe adjustment.

Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society Membership

The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society has a new Membership Secretary, to whom you should write if you wish to join:

Manuel Trucco

Tune Book in Process

Matt Seattle, who has produced many fine tune books over the years, is assembling a book of Border tunes for the Lowland bagpipe and Scottish smallpipes. For more information, write to Matt:

Confused?

Judging by the influx of letters and phone calls on the topic, many smallpipers are confused by the behavior exhibited over the past few years by Scottish smallpipe teachers as they make their stateside rounds. You may wish to contemplate the following: lacking a clearly defined tradition, they are staking their claims towards the invention of it.

7

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Dear Editor,

I received my first copy of the Journal and it is very impressive. You have certainly put in some hours making it happen and have done great job. The following results of the first Scottish small pipe contest to be held in this part of the country might be of some interest.

Scottish Small Pipe Competition at the Santa Rosa Indoor Piping and Drumming Contest Piner Elementary School, Santa Rosa, California March 6, 1993

1st Place: Martha Yates; Pipes: H. Moore, Key of A Tunes: The Martha Yates Polka (by Donald Shaw Ramsay); Drops of Brandy; Ash Grove (Martha sang along with this tune)

2nd Place: John Allen; Pipes: M. MacHarg drones, H. Moore chanter, Key of A Tunes: The Old Man on the Moor; The Merry Boys of Greenland; High Over Bunachton

3rd Place: Paul McAfee; Pipes: J. Anderson, Key of A Tunes: Leaving Loch Boisedale; The Merry Boys of Greenland; Forest Lodge

Sincerely,

John Creager

April 30, 1993

Dear Mr. McCandless:

Enclosed you will find my copy of the letter I received from Julian Goodacre informing me of my winning the trophy for the L.B.P.S.’s overseas event. Though I am unduly proud of this and my ego would inflate to gigantic proportions from having the news published in the Journal, I wonder if a short listing might have the very positive effect of encouraging others to participate next year. Also, please find enclosed…my dues. The Journal has been a source of great enjoyment and inspiration. Keep up the good work.

Cheers,

John Dally

8

JULIAN GOODACRE BAGPIPE MAKER

JULIAN GOODACRE BAGPIPE MAKER

4 ELCHO STREET, PEEBLES, SCOTLAND 22.4.93.

Dear John,

Congratulations on winning this years ‘Goodacre Trophy’ in The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society Competition. It was judged by the Committee who wanted to make it very clear that although yours was the only entry received you did not win by default. You played a very commendable set.

Your trophy, which you get to keep, will be posted separately. It is a full size copy of The Montgomery smallpipe chanter. You only get half of it, but if you win in 1994, then you will get another half!

This was the only class available for overseas entry, but the Committee agreed that it would be good if your composition was published in Common Stock. Do you have it written out, and if so could you send it to Jock Agnew? I believe he has a computer set up to write music, so don’t worry if your copy is not neat enough for publication!

Sadly I was in the USA when this was judged, so haven’t yet heard your entry, though hope to next week when I see Manuel Trucco. Do you mind if he uses all or some of your entry on the next Samisdat tape? He may want to- I don’t know. If you are agreeable to this then write him a note.

Your trophy will be posted as soon as I can get your certificate signed by Gordon Mooney.

Well done!

9

Dear Brian: September 2, 1993

Here’s a short bit about my re-enacting mania. If you want more of this, let me know. I first became interested in Northumbrian piping when I found a record of Billy Pigg. Shortly after that I was in New York and found the 1967 edition of the smallpipe plans in the library, and in 1975 I made the set I’m still playing, though I’ve switched to a chanter made by John Addison. I spend most of my time these days making banduras, a Ukrainian harp-like instrument. I used to do nothing but tour and play concerts but now life is quieter. The Journal is wonderful. Keep up the good work.

Picture this scene. A piper is seated on a bench next to a wall in a room about 15 by 15 feet. The room is filled with revelers dressed in knee britches, philamors, hunting frocks and other eighteenth century garb. The ladies are decked out in their finest gowns. Some are dancing, some are shouting, and one or two merciful souls are making sure that the piper is well lubricated.

Is this a scene out of a Hogarth drawing, or a painting hanging in some ill-lit corner of a museum? No. This is a description of me at one of last Spring’s living history events. Yes friends, there are places where you can live out all of your eighteenth century fantasies and even get paid for it (not often, but it happens). When I moved here, to North Carolina, I joined the North Carolina Rangers – a group that tries to recreate a Revolutionary War Loyalist Militia unit. We take part in re enactments of Revolutionary War battles and demonstrate to the public what life was like for eighteenth century people with as much accuracy and detail as we can.

We wear the clothes, eat the food, smoke from clay pipes, start our fires with flint and steel, and so on. I quickly discovered that there are never enough musicians and pipers are especially welcome, Border and Northumbrian even more so.

Mostly I can play anything I want, but I try to keep it within the period. People actually request pibroch! The war pipes are usually used during battles, and the pipers are usually connected with one of the highland regiments, the 42nd, 71st, or the 84th. If you’d rather not be part of a line regiment there are always militia groups to join. Being part of these groups has given me a greater understanding of the music I’m playing since it puts it in context. You get to star in your own movie. You get to feel what it is like to be the driving force behind forty people dashing about in Dionysian frenzy! More often than not this takes place around a camp fire – the combination of woodsmoke and a good single malt is unbeatable.

If this sounds pretty good to you and you’re asking yourself how you can get involved with this, read on. The easiest way to contact some of these groups is to go to one of the events and talk to the participants. If there is a National Battlefield near you where a Revolutionary War battle occurred, ask them about re-enactment groups. If all else fails, ask me.

As far as getting outfitted, it depends on the group you join. If you are part of a numbered regiment of the line, you will have to come up with the proper uniform. This can get pretty pricey. Its lots cheaper if you learn to sew! I always wear 18th century highland gear. The philamor, tartan cloth five feet wide and five yards long. You can use any pattern you want. Contrary to 19th century Romantic notions, they

10

didn’t have clan tartans in the 18th century. I wear the standard drop sleeve shirt, westkit and caddagh instead of knit socks. The buckle shoes were the most expensive thing, but I wore mocassins until I could afford the shoes. Highland currans are cheap and simple to make. My musket was the biggest investment, but you don’t have to own one if you’re the piper. Camp gear you acquire over time. I’ve gotten lots of great stuff through trades.

What I love about doing all this living history stuff is that I learn more about the music, meet a lot of wonderfully interesting people, get a lot of neat stuff, eat and drink in grand fashion, and I’m surrounded by people who want to hear MORE PIPES. It may not be heaven but its as close as I’m likely to get. If I can answer any questions about all of this for you, give me a call.

Ken Bloom

An Open Letter From Patrick Sky

(The following letter was sent across the e-mail Bagpipe network and is published here with permission of Mr. Sky.)

8-27-93

To all friends of Uillean Pipes:

Uillean piping has changed significantly since I found my first set of Rowsome pipes in a New York City bar in 1970. When I first took up the pipes the only other pipers in the United States, that I was aware of, was Dennis Brooks, Tom Standeven, Joe Shannon, and Tom Busby. We were so scattered that helping each other was really not feasible. I cannot remember a day going by that I was not frustrated and afloat in a sea of ignorance.

I tried my hand at pipe making and flute repair between the years 1973 and 1978. I made mostly practice sets, copying Rowsome. My sets played well and were in tune. As far as I know I was the first to make a plastic bag, the first to use commercial tubing for reeds, and was the first to use tubing lined reed seat for the chanter and regulators. The reason that I am bringing all of this up is because I have made many years worth of mistakes and speak with experience when I criticize pipe makers and piping.

I’ve been at the pipes for around 22 years now and after making thousands of reeds, I don’t know how many chanters and five or six 3/4 sets. After suffering through bouts of elation and disgust, I finally have my set of Leo Rowsome pipes going almost perfectly. I say almost perfect, because the one thing that I have learned in all of these years is that there is no perfect chanter and that playing in tune is always a compromise between the pipes, the reed, and the player.

11

Over the years I was your average fanatic; piping friends and loved ones away. I have read articles and shared information about pipe making and reed making with luminaries such as Tom Busby, Dan Dowd, Tim Britton, Matt Kiernan, and others about how to get a set of pipes going. There are a few books also explaining reed making. I even wrote a couple of books myself: “The Insane Art of Reed Making” 1973 and “A Manual for Uillean Pipes” 1978.

Here is the problem: When Leo Rowsome died, the last great traditional pipe maker took 200 years of pipe making knowledge with him. Leo had no apprentice to carry on four generations of pipe making traditions. Instead, he left a vacuum that has been filled with self made EXPERTS, hundreds of truths, half truths. theories, and harebrained ideas, all mixed together so that it is hard to know what to believe. One fact remains: All sets of pipes made after Leo Rowsome’s death, whether in Ireland or in the U.S., are copies of old pipes. These new sets are produced by self made, sometimes talented and sometimes not so talented, pipe makers with no first hand knowledge of the traditional craft of pipe making. A set of copy pipes is only as good as the original set that is copied, plus the talent of the pipe maker. If either of these two factors are not present – talent and a good set of pipes – then a bad set of pipes is the result.

Uillean pipe making has always been a home shop affair. Today’s pipe makers are individualistic and uncooperative, if not outright critical of each other. While the pipe makers fight with each other and spread their dubious theories as to which is the best; the large bore, the small bore, the large finger holes, the small finger holes, large volume or soft and sweet, the kinds of wood, the reeds, and reed makers squabble over staples, width, length, can, etc., etc., the person who simply wants to play the pipes and enjoy the music are in a sense, victims of not only this constant bickering but the pocketbook as well.

All pipe makers today have one thing in common: they have their own method of pipe and reed making that is based on the dimensions of the pipes that they possess, reflect a total lack of standards. What knowledge they do possess was usually gleaned from experimentation. Having your own method is not something to brag about. What we need is a shared and standardized method that can be easily taught to all.

Today there are pipe makers, some of them complete frauds, who are turning out unplayable instruments at an unprecedented rate and selling them for exorbitant sums. I get calls every month from people who have purchased sets of pipes for large sums of money, only to be cast afloat and left to their own devices. It seems that many new sets of pipes are not even playing well at the time of purchase. As a matter of fact I have never heard a full set of pipes made by ANY of the new pipe makers that was playing well, I mean regulators and all. This has got to stop.

I believe the root cause of all of the problems associated with pipe making and reed making is “lack of standardization.” Without standards knowledge cannot be shared very well. What we need is to emphasize what pipes and reeds have in common not what sets them apart. I am not talking about tone here. Violins for example have an almost identical shape, neck, bridge height, etc., but the makers individually have enough leeway to express themselves through volume and tone. This is not a new problem. In the past, the closest piping ever got to standards was when a pipe maker, such as Leo Rowsome, dominated an era.

12

We should learn from the Scots/Irish bagpipers who over hundreds of years have developed standards in reed design, chanters and even the way the music is written down, and make some kind of attempt to create a standard “D” chanter and with it a standard reed. The advantages to this should be obvious to everyone. If we had a standard, a good reed maker could make standard reeds by the hundreds and sell them in batches just like the Scots/Irish bagpipers; through the mail, drawing the Uillean pipe community closer and insuring the survival of the instrument. Standardization would help teaching tremendously, two or three students could be taught at once with chanters that are of the same pitch. True classes would be possible. It would bring the prices down which are at this point on the verge of making piping a pastime of the wealthy.

I would like to argue for those who want an instrument that plays well, sounds good and that is standardized so that reeds are easy to obtain. I do not want to pay thousands of dollars to purchase EXPERIMENTS that are unproven. I do not want to pay as high as forty dollars for reeds that may or may not work. I do not want to purchase a set of pipes unless it is going perfectly. I want my pipes to be in concert pitch so that I can play music with others. I want some kind of guarantee, if I am unsatisfied I want the right to return the pipes for a refund. I want a small book that includes the reed measurements for the new set of pipes so that a good reed maker can make reeds that will fit.

How do we get pipe makers to agree on a standard chanter? Perhaps we can’t, but we must try. We must not be intimidated by the expert – remember the last EXPERT died in the sixties. We have a right to criticize and to demand a good product. We must convince the pipe maker that it is in his best interest to participate in standardization. Barring that, the pipe maker must make a good playable set of pipes and realize that failure to do so will result in a loss of business.

Of course, every pipe maker has developed his system of pipe making and has his completely subjective opinion as to what is the BEST. This is of course natural, it leads to experimentation and eventually improvement of the instrument. However, the pipe maker does not have the right to sell “experimental” pipes to unsuspecting buyers. He must sell only pipes that are a final working design. We need to convince the pipe maker that the purchaser be given a choice of between either a standard set of pipes or a set of the pipe maker’s own design. Obviously if the pipe maker’s set is better, then people will buy it.

Some pipe makers will balk at this idea and still wish to make and sell pipes of their own design. This is alright, but in my opinion, they are morally and ethically obligated to at least deliver the pipes in FULL WORKING ORDER and to furnish reed, bore information, and measurements to the purchaser, so that the pipes can be made to play by “any good reed maker.” An instruction booklet containing this information should be sent with every set of pipes. Any pipe maker failing to do this should be shunned by all, and if possible, put out of business.

I believe that it is time for the Uillean Pipe community to get itself together and to stop the bickering and backbiting that has almost led the instrument to extinction. We must try with all our might to eliminate that horrible question: “How are your pipes going?” I believe that the way to improvement is through standardization and criticism.

Patrick Sky

Dear Fellow Piper:

I awoke my sleepy eyes from the land of hush-a-by to find myself in Elkton, Maryland. I scrambled to breakfast at the local restaurant with pipes in hand. On then to the American Legion Hall in Elkton for the first-ever meeting of the Lowland and Border Pipers. Much to my surprise there were pipes on display from around the world. Scottish, Irish, French, English, German, French Court pipes, Bulgarian, Italian and many more. Hurdy gurdies were also seen.

Soon the pipes were playing. French court pipes with hurdy gurdy playing in harmony, my heart was beating fast. I never in my life had ever heard such sweet sounds. English small pipes or “Northumbrian” pipes started up with Sam Grier piping. I so enjoyed the sound in the hands of such a Master player. He played his double ivory chanter on the border pipes – a treat that soon brought a large crowd. I asked him about his pastoral pipes and said I had never heard a set playing. So he reached over, got his set, and what a wonderful sound of music there was before me. Why wasn’t I born in the 1700’s? Oh well… The next set was the French musette of which I had only heard recordings of.

Dinner was served and what meal it was, pot roast, potatoes, corn and all you could eat!

The evening concert was next with a wonderful set of “G” key German pipes. “My God, what a deep and resonant sound” with the hurdy gurdy playing. Uilleann pipes, pastoral pipes, lowland pipes, small pipes and highland pipes one right after another. “Baines would have cheered.”

The dance followed with many line dances with all different pipes playing for each set. A wonderful party at Brian McCandless’ house wrapped up a most wonderful day. I didn’t want to leave Elkton, but a bus beckoned and the Song of the Sirens (pipes) called.

Thank you Brian and your lovely wife for a wonderful time. looking forward to next year,

Rick O’Shea, Uilleann Piper

CALENDAR 1993

October 16 and 17. 1993: “A Gala Rant”. Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society Collogue at Old Gala House in Galashiels. Featuring lectures by Fred Freeman, Jon Swayne, Matt Seattle, Joan Flett, Colin Ross, Goodacre Brothers, and Andy Hunter. Exhibition of Alan Jones’ bagpipe collection. Concert featuring Hamish Moore and Dick Lee and the Hungarian folk group Vasmilong.

April 1-3. 1994: Pipers’ Days in Elkton, Maryland. Exhibition, Workshops, and Dance Concert.

August 27-29, 1994: Tenth Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention, North Hero, Vermont – Your support and encouragement are needed to make this one happen, please write to Alan Jones, P.O. Box 130, Rouses Point, New York, 12979.

14

WELCOME TO THE N.A.A.L.B.P. AND BELLOWS BAGPIPING By Brian McCandless

The Association

The North American Association of Lowland and Border Pipers (N.A.A.L.B.P.) was founded in 1989 by Brian McCandless to provide a network for North American players of bellows pipes and a forum for pipers to share information and music.

Our name is derived from the name of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society across the Atlantic Ocean and reflects both lowland Scots and Northumbrian influences in the development of Lowland and Border pipes and of bellows-blown smallpipes. These days, the diverse piping influences among our members may make our name seem a bit too specific, so allow me to say that the name serves as a banner heralding a collective common interest, not as a rigid definition.

The original membership mailing went out in early 1990 to 48 people across Canada and the United States and was compiled from mailing lists kindly provided by two modern itinerant pipers, Alan Jones and Hamish Moore. As you will see in our current membership list at the back of this issue, there are now over 150 people involved in the Association. To our charter members I say thank you and to our new members I bid you welcome!

The association was originally conceived to run as a “democratic” organization, but force of numbers and the extent of the North American continent have not permitted implementation of that program. For that reason, the association has been run by an elected committee consisting of Brian and Michele McCandless, Mike MacNintch, and Alan Jones. Through their cooperation and with the support and advice of people such as Steve Bliven, James Coldren, John Dally, Sam Grier, Richmond Johnston, and Michael MacHarg we have kept up with two of our goals in the past years, namely, publication of a bi-annual Journal and hosting of an annual gathering. The first N.A.A.L.B.P. Pipers’ Day was held in Elkton, Maryland on April 3, 1993 and we are planning the second, a multi-day event, tentatively to be held on the weekend of April 1, 1994. For the past two years we have co-hosted the Northumbrian Pipers Convention in North Hero, Vermont where we have had the opportunity to meet and study with Lowland pipe, Scottish smallpipe, Uillean pipe, and Pastoral pipe players such as Sam Grier, Gordon Mooney, Hamish Moore, Chris Ormston, Jerry O’Sullivan, and Ray Sloan. The Vermont convention, run by Alan Jones, has also served to introduce us to some of the finest pipe makers of our time, notably Michael Dow, Michael MacHarg, Hamish Moore, David Quinn, Colin Ross and Ray Sloan.

Future goals of the association are to produce a cassette of the playing of our members, a beginner’s manual for pipe playing and maintenance, and a tunebook of music adapted for the smallpipes, drawing on our members’ diverse cultural backgrounds and interests.

15

The Instruments

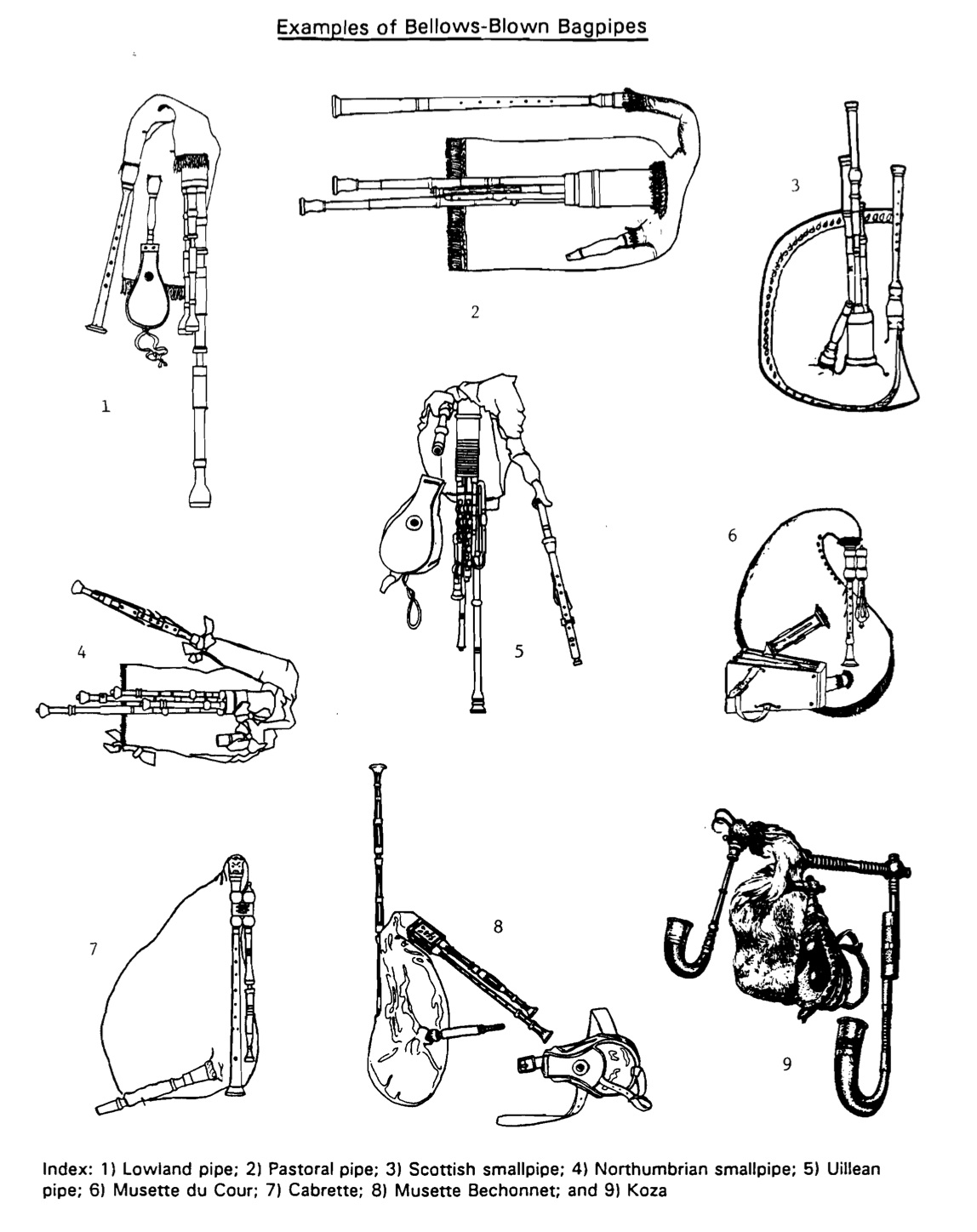

Many people have written in asking me to explain the differences between the various kinds of pipes we play. In some cases, the person is trying to decide on a type of instrument to purchase. For that reason I wrote a short article in Journal #1 which briefly outlined some of the differences. In addition, Mike MacNintch assembled a discography documenting the use of various pipes in the recorded medium. We try to update and run the discography once per year and you will find it in this issue. Unfortunately, Journal #1 is out of print so I offer you the following short descriptions which I hope you’ll follow up by consultation with the discography and with other members. We do plan to republish the articles from the first four Journals as a combined monograph. A/so, books such as Bagpipes by Anthony Baines (1960) are indispensable resources which should be sought out for their photographs, detailed descriptions, histories, and references. In the paragraphs below are brief descriptions of bellows-blown bagpipes from across Europe, namely Lowland pipes, Pastoral pipes, Scottish smallpipes, Northumbrian smallpipes, Irish pipes, Musette du Cour, Cabrette and Musette Bechonnet, and the Dudy/Gajdy/Koziol family of pipes. Simple line drawings of each appear together at the end of the article.

Overview

We do not know who first applied the bellows to the bagpipe, but the concept of a bellows-blown woodwind instrument is positively ancient, as a 4th century illustration of a portative organ on the Obelisk of Theodosius attests (see Musical Instruments of the World, UNICEF, 1976, p.82). In its common form a bellows is a flexible leather chamber bounded by two wooden naps. A one-way air intake valve and exhaust tube allow air to be drawn into the bellows then compressed into a bagpipe. A one way “clack” valve inside the bagpipe blowpipe prevents air from returning to the bellows so that it must exit through the instrument’s reeds and thereby set the reeds vibrating.

In the context of bagpipes, we find a wide occurrence of bellows in 17th century art, beginning, for example, with Michael Praetorius’ (1619) detailed sketch of a Musette du Cour (see Syntagma Musicum, WolfenbUttel, 1619). From there, the bellows bagpipe appears in numerous cultural contexts across all of Europe. In the past two centuries, the bellows pipes have variously maintained a place in the cultures of Northumberland, Ireland, Poland, and France where innovative makers have successfully achieved instruments capable of performing in a staccato manner. Recent decades have witnessed an increase in the popularity of all forms of bellows blown pipes and one in particular, the pastoral pipe, is in the infancy of its revival.

16

“Why bother with a bellows?” is a question I hear often. I don’t think any one answer does the job, especially considering the different cultural contexts and technical aspects of some of the pipes. So I give three appropriate responses which, taken together, provide a basis for discussion – talk amongst yourselves:

1. The bellows is a dry form of blowing which is less damaging to thin wood/cane reeds over a long period of use.

2. The player is free to sing/smoke/talk while playing.

3. The player’s face is not necessarily contorted by playing the instrument.

With this in mind we can move onto the descriptions and drawings of bellows blown pipes. As a musical instrument the bagpipe has certain inherent limitations which makers and players have learned to overcome through the ages, resulting in some of the highly developed instruments discussed below. Some of these musical limitations involve note articulation, chromaticism, scale, and pitch. When I refer to the pitch of a bagpipe, I mean the note sounded with six fingers and the back thumb down on the chanter. This is the tonic or fundamental or keynote and is the note to which the drones are generally tuned in their various octaves. Do not confuse the key of a bagpipe with a metal key on a bagpipe chanter or regulator. I use the term “complex drone” to refer to drones which can be re-pitched by use of a revolving perforated ring (or “bead”) on the drone tube. In this article, I will capitalize the names of bagpipes for emphasis, although this practice is not generally followed in musicological literature.

17

18

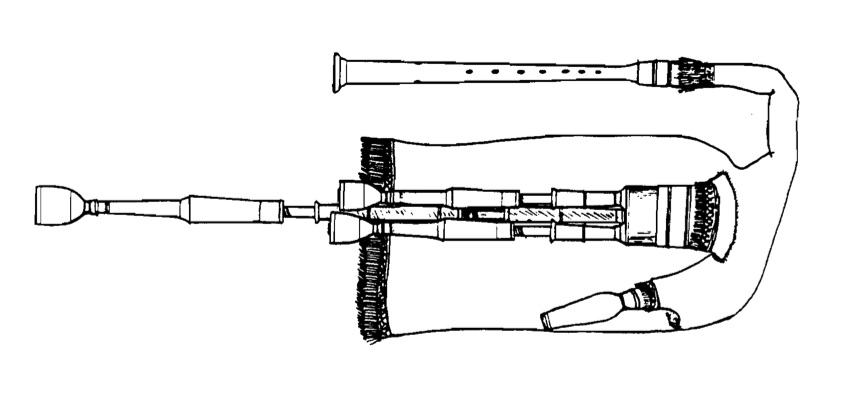

Lowland and Border Pipe

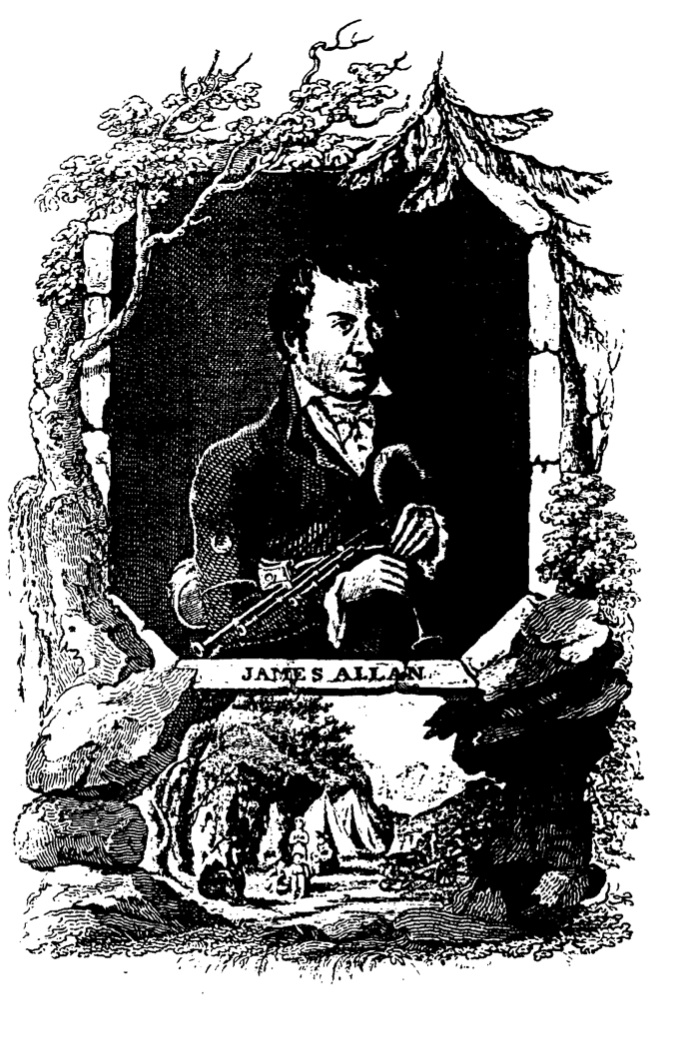

These pipes, so named for their early geographical occurrence in the region bordering Scotland and Northumberland bear a resemblance to both the Scottish Highland pipes and to the central French Cornemuse. They gained notoriety as the instruments of the 17th and 18th century village waits, or town pipers, and their heyday culminated with the colorful exploits of the border reivers and of the rags-to riches-to-rags piper Jamie Allan. After the passing of the town pipers, the instrument fell into limited use until its reincarnation by Cocks and Robertson in the early part of the 20th century as the “half-long” bagpipe.

The Lowland pipe has a conically-bored chanter with a double-bladed reed which produces a loud nasal whine but which is generally quieter than the Highland pipe. The chanter is reeded in such a way as to be able to overblow into the second octave which increases the melodic range in a manner akin to the French Cornemuse. The drones are nominally cylindrically-bored, are reeded with single-bladed cane reeds and are carried in a common stock.

Nowadays the drones can be obtained in a variety of configurations, a common one being tenor/tenor/bass, which is similar to that of the Highland pipe. Some makers have added a deeper contrabass drone and/or drones pitched a fifth higher than the tenor or even a fourth between the bass and tenor. Typically the chanter plays a major scale pitched in A or B-flat with a flattened or even neutral seventh, but a variant with a sharp seventh has been discovered (see Ray Sloan’ article in Journal #4, p. 52). Makers of different interpretations of this instrument include John Addison, Jimmie Anderson, Mike MacHarg, Hamish Moore, David Naill and Co., Ray Sloan, and Jonathan Swayne. Geordie Syme and Jamie Allan were notable players of this bagpipe in the early 19th century. Modern players include Alan Jones, Gordon Mooney, Hamish Moore, and Jean Pierre Rasle.

19

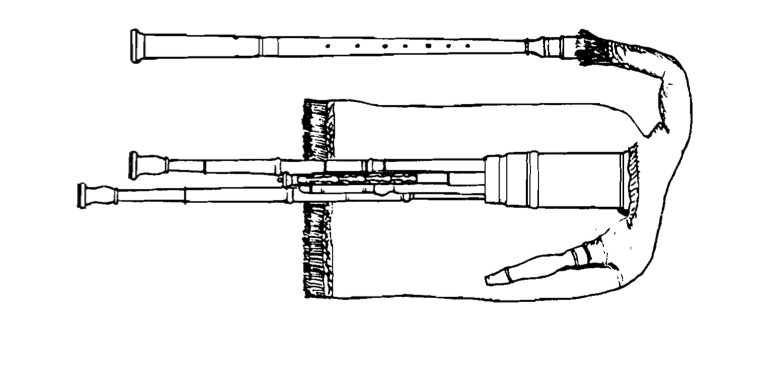

Pastoral Pipe

This pipe bears much in common with the Lowland pipe and has many refinements that make the instrument more versatile but at the same time harder to master. It is named (we think) for its role in John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera (1728) which featured a “pastoral scene” including the bagpipe. The opera was later referred to as Gay’s “Newgate Pastorale” after London’s Newgate prison which was the setting for the story. Illustrations by William Hogarth and others depict the instrument in the context of the opera, and numerous extant Pastoral pipes of that period are to be found. They all have a very long, narrow-tapered conical bore which carries a removable foot joint. The narrow bore and long foot-joint allow the chanter to be overblown well up into the second octave while retaining the basic fingering system of the Lowland pipe. Recent advances in reeding the instrument by Sam Grier prove that a full two octave range was possible, with at least two ways of playing the chanter across the octave break. The tone of the Pastoral pipe is unique – a quiet nasal voice which blends like a bell into its drones. The drones are carried in a common stock in an arrangement that evolved over the 18th and 19th centuries. A common feature is that the bass drone is folded back on itself, either within the main stock (pre-1800) or externally (post-1800). Any number of drones are possible, with two (baritone/bass) or three (tenor/baritone/bass) being common on the earliest instruments. Sometime in the late 1700’s, regulators were added alongside of the drones to permit chordal accompaniment to the chanter melody. The regulator is essentially a chanter that is all closed up by a stopper and spring-loaded metal keys. The instruments were pitched in E-flat or D. Some antique instruments carry metal keys on the chanters to allow truer chromatic notes (e.g., 8-flat) than can be obtained by cross-fingering. Some instruments have been made entirely of ivory although boxwood, cherry and blackwood were widely used. A careful examination of several 18th and early 19th century engravings of “gentleman” pipers reveals their instruments to be the Pastoral bagpipe, despite the fact that the title or label may indicate “Irish” or “union” pipes. A dead giveaway in these illustrations is the foot-joint extension on the chanter. The notable Northumbrian pipemaker Robert Reid made pastoral pipes; in recent years, Chris Bailey, Colin Ross, John Addison, Mike MacHarg, and Brian McCandless have made Pastoral pipes to measurements of extant instruments of the 18th century. Jamie Allan was reputed to be a player of this pipe in the early 19th century. Modern players of the instrument include Hamish Moore, Sam Grier, Joe Moir, and Brian McCandless.

20

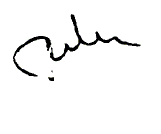

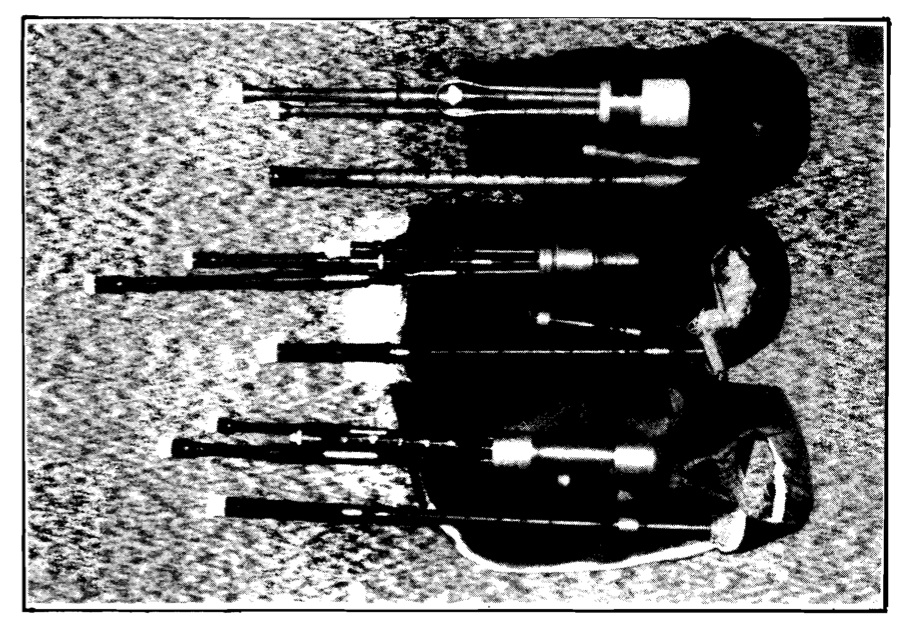

Three recent Pastoral bagpipe replicas.

Top: Copy of mid-18th century pipe by W. Squire, Stirlingshire. Pitched in E-flat with 3 drones. Cherrywood and brass. Made by Brian McCandless.

Mid: Copy of early 19th century pipe by Naughton. Original rests in the Kinguissie Castle Museum. Pitched in D, three drones, one regulator. Cocobolo wood and brass. Made by Mike MacHarg.

Bottom: Adaptation of early 19th century pipe by R. Reid (?). Original rests in Blackgate Museum, New Castle. Two drones, one regulator. Blackwood and brass. Made by John Addison.

21

Scottish Smallpipe

This is the pipe played by the majority of our members, and it is a favorite of Highland pipers for indoor playing. It has also found a place among non-piping musicians in that it is a forgiving instrument to finger while producing a beautiful tone. Among the earliest known examples is the “Montgomery” set dated 1757, as discussed by Hugh Cheape in Common Stock (Vol. 4, No.1, 1989). In Northumbria this type of instrument dates to the mid-17th century where it served as the progenitor of the Northumbrian smallpipe. Its chanter is related to the so-called ·practice chanter” used today by Highland pipers. Other relatives of the Scottish smallpipe include the mouth-blown Dudey and Hummelchen noted by Praetorius and the French Musette du Cour.

The Scottish smallpipe has not been standardized to a single pitch, reeding, or drone configuration: it can be obtained in pitches of low G, A, B-flat, C, D, E-flat, F, and high G and with as many as six complex drones with on/off plugs or switches. In its simplest form it consists of a cylindrically-bored chanter with three drones in a common stock tuned alto/tenor/bass. Many makers are offering instruments with interchangeable chanters and drones so that a single bag can be used to play in different keys. The sound of the chanter is very dependent on the pitch chosen but a general feature is that it produces something of a buzz,and the tonic note (six fingers down) gets lost in the drone, unlike the Highland or Lowland pipes where the “high A” seems to disappear into the drones. For this reason, some Highland movements like birls and grips are not as effective as cut notes played high up on the chanter. Quite apart from the usual Highland style of fingering, a completely closed style can be employed to great effect, using the six finger note as a reference point in staccato playing between each melody note – it vanishes into the drone giving the illusion that the chanter is stopped between melody notes. A similar style of playing is used on the Northumbrian pipes, the Musette du Cour, and the Cabrette. The chanter range can be extended by the addition of metal keys to obtain notes above the thumb hole and natural notes within the scale. Many makers exist, both in North America and in the United Kingdom (see list of makers). Modern players of the instrument include lain Macinnes, Gordon Mooney, Hamish Moore, Rab Wallace, and Robin Williamson. Hamish Moore and Gordon Mooney have run piping schools across North America for the Scottish smallpipe.

22

Northumbrian Smallpipe

The Northumbrian smallpipe began its evolution as a form of the Scottish smallpipe, but its chanter was eventually closed at the bottom which allowed for a very articulated staccato style of playing and for keyed notes well below the tonic. Tradition has the instrument pitched in F or F-sharp with a few being made in G and low D, all with four complex drones. Early instruments were unkeyed, but during the past century instruments with as many as 21 keys have been made. The playing technique and gracing of the Northumbrian pipe is well developed, which is attributed to its long unbroken tradition and development earlier in this century. The increased popularity of the instrument in recent decades was facilitated in part by the enthusiasm of Lance Robson whose family had a long history of piping and tune collecting. Today Lance travels widely to teach Northumbrian pipes and pipe maintenance. Robert Reid elevated the making of this instrument to a fine art as many of his extant instruments in ivory and silver attest. Modern instruments are built in blackwood with brass ferrules and tuning beads. Recent makers include John Addison, Dave Burleigh, Heriot and Allan, David Quinn, Colin Ross, and Ray Sloan. It has been used in venues ranging from traditional sessions to accompaniment of soft rock music such as on Sting’s recent release “Fields of Barley” with Kathryn Tickell playing the Northumbrian Smallpipes. Other players to listen to are Richard Butler, Pauline Cato, Ged Foley, Anthony Robb, and Dave Shaw. For more information, contact the Northumbrian Smallpipes Society c/o Richard Shuttleworth.

Irish (Uillean, Union) Pipes

At a glance the fully developed Uillean pipe is the most complex of the bellows blown pipes, carrying a chromatic chanter capable of two octaves, four drones with an on/off switch, and three to six regulators capable of providing organ-like chordal accompaniment. Early examples bear a close resemblance to early pastoral pipes, and their historical relationship has been often discussed. The most telling distinction, though, is the absence of a foot-joint on the Uillean pipe. This absence permits “playing on the knee” in staccato fashion. The most common pitch of modern instruments is D, although nothing can quite compare to the low groan of a “flat set” (pitched from C to B-flat). Modern players include Tim Britton, Tom Creegan, Liam O’Flynn, Paddy Keenan, Patrick Molard, Davey Spillane, and Jerry O’Sullivan. For more information on the history and people associated with this instrument, may I recommend Captain Francis O’Neill’s book Irish Minstrels and Musicians (1913) (now in reprint from Celtic Music, 24 Mercer Row, Louth, Lincolnshire, England). You can learn more through Na Piobairi Uillean, 15 Henrietta Street, Dublin 1, Ireland.

23

Musette du Cour

This most diminutive of bagpipes is the one portrayed by Praetorius and for many years enjoyed the attentions of the upper class of French society during the 17th and 18th centuries. It consists of an open ended chanter (grand chalumeau), a parallel mounted keyed chanter (petit chalumeau), and a shuttle containing four to six internally folded drones (bourdons) tuned by means of moveable sliders (layettes). All of the pipes – chanters and drones – are reeded with double-bladed reeds which gives the instrument a bright presence. The chanter carries several keys for playing chromatic scales and is typically pitched in C. It is thus suited for duets with hurdy gurdy and harpsichord which, together with its compact shape and capabilities contributed to its popularity among “baroque” and “classical” artists. Many pieces were composed for the Musette du Cour by the likes of Baton, Chedeville, Couperin, and Hotteterre and two detailed treatises for playing the instrument were produced: Traite de la Musette (1672) by Charles-Emmanuel Borjon and Methode pour la Musette (1737) by Jacques Hotteterre. Two recent books have excellent articles by the leading modern player of the Musette, Jean-Christophe Maillard. They are Cornemuses – Souffles Infinis, Souffles Continus, Geste Editions (1991), ISBN 2 905061-47-2 and Proceedings of the International Bagpjpe Symposium, Uitgeverij (1988), Utrecht (available in French from: Stichting Volksmuziek Nederland, P.O. Box 331, 3500 AH Utrecht, The Netherlands).

Cabrette and Musette Bechonnet

Descendants of the Musette du Cour, these folk instruments are currently in widespread use throughout France and North America, particularly in Quebec and in the American west and northwest. Their distinctive feature is the conically-bored chanter mounted parallel to a drone.

The Cabrette was invented around 1800 in Paris by displaced Auvergnats and was no doubt inspired by the Musette du Cour. The name “cabrette” is derived from the middle Latin word for goat, so-applied for the skins used for bags in the early days. The name shares a linguistic heritage with other pipes, notably the Chabrette (Limousin), Chevre (Langued’oc), Chuvash (Russia), Koza (Poland), and Chiboni (Adzharia). The Cabrette, like the Pastoral pipe, has small finger holes with fairly thick chanter walls which produces a distinctive nasal tone. Its chanter and drone are mounted in separate tubular stocks bound together by wires or sheet metal and share a common air supply which enters through the chanter’s stock and passes through to the drone. A consequence of this is that the air pressure supplied to the chanter reed is modulated by the slower beating single-bladed drone reed which together produce a horrendous buzz. Thus, many Cabrette players use no drone and play in concert with accordion or hurdy gurdy, which have strong drones. Other players use a modified drone known as a chanterelle which has a double-bladed chanter reed and a modified drone which sounds very pleasant. Modern players such as Jean Bergheaud, Antonine Bouscatel, Martin Cayla, Louis Rispal, Pierre Ladonne (and former generations of Ladonnes), and Eric Montbel use a technique called picotage

24

which pits the melody notes against the chanter’s six-finger note in rapid alternation. On an undroned instrument this technique gives the illusion of a drone.

The Musette Bechonnet is named for Joseph Bechonnet who, around 1850 in Effiat, on the border between the Auvergne and the Bourbonnais, improved the regional two-droned Cornemuse by adding a bellows, adding a third drone, and fitting the drones with metal reeds. The chanter, like that found on the Cornemuse, is capable of overblowing up to three notes above the high thumb note. It is mounted in a very decorative rectangular stock together with the tenor and treble drones. The bass drone is mounted in a manner akin to the “Flemish” pipes portrayed by Brueghel and protrudes up and out from the player. The Musette Bechonnet, like its ancestor the central French Cornemuse, is tolerant of many fingering styles and techniques. The instrument can be heard in the playing of Robert Amyot, Jean Blanchard, Bernard Blanc, Les Brayauds, Brian McCandless, and Jean-Pierre Rasle. Modern makers of the instrument include Bernard Blanc, Dominique Bouge, Remy DuBois, and Mike MacHarg.

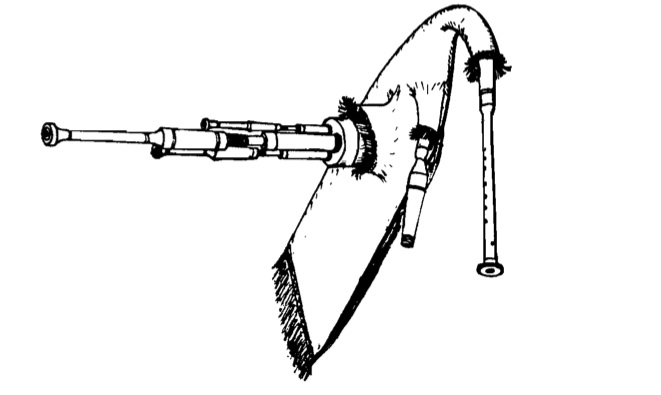

Dudy, Gajdy, Koza, Bock

The pipes called Dudy, Gajdy, Koza, and Bock are all members of a family of bagpipes found at one time throughout Europe but which today are played in countries east of Germany. The Czech word “Dudy” is plural for “Duda”, and means “Bagpipe”, like the German word “dudelsack”. The names Koza (Polish) or Koziol (Wendish) and Bock (German) refer to the goat used to make the bag. The pipes we are concerned with here are bellows-blown, have a cylindrically-bored diatonic chanter with a single bladed reed, a single drone, and a goat-skin bag. It is not clear when the bellows was added, but this style of bagpipe design is over 1000 years old! The chanter and drone on these pipes emanate from ornately turned and carved stocks and are fitted with large horn or brass bells. A photograph of a 16th century Polish pipe with two drones appears in Plate XIX of Anthony Baines’ 1967 book entitled Woodwind Instruments and Their History (reprinted by Dover Publications in 1991).

Typically the chanter has 7 holes on the front and a thumbhole. Although the pipes occur in many pitches, D, E-flat, and F seem to be the most common. The fingering systems differ also, but a common one (e.g., the Czech Dudy) has a bass E-flat drone with the chanter scale progressing: B, D, E-flat, F, G, A-flat, B, and C. Thus the drone is pitched an octave below the five finger note of the chanter. On the Polish Koza, the drone is tuned to the seven finger note (all down on chanter) while the Polish Gajdy has the drone tuned to the four finger note.

Another distinguishing feature of these pipes are the bass drones. On the Polish Gajdy and Koza the bass drone bends over at the player’s shoulder and extends downward at a modest angle. On the Czech Oudy, the Boemischer Bock, and the Polish Dudy Wielkopolska the bass drone is folded back on itself with curved tubing (like seen on the Uillean pipe) to shorten the length. Like the Gajdy and the Koza, the Dudy and Bock drones hang down over the shoulder. Occasionally one will see the drone hanging down the front, as on the Egerlander Bock.

25

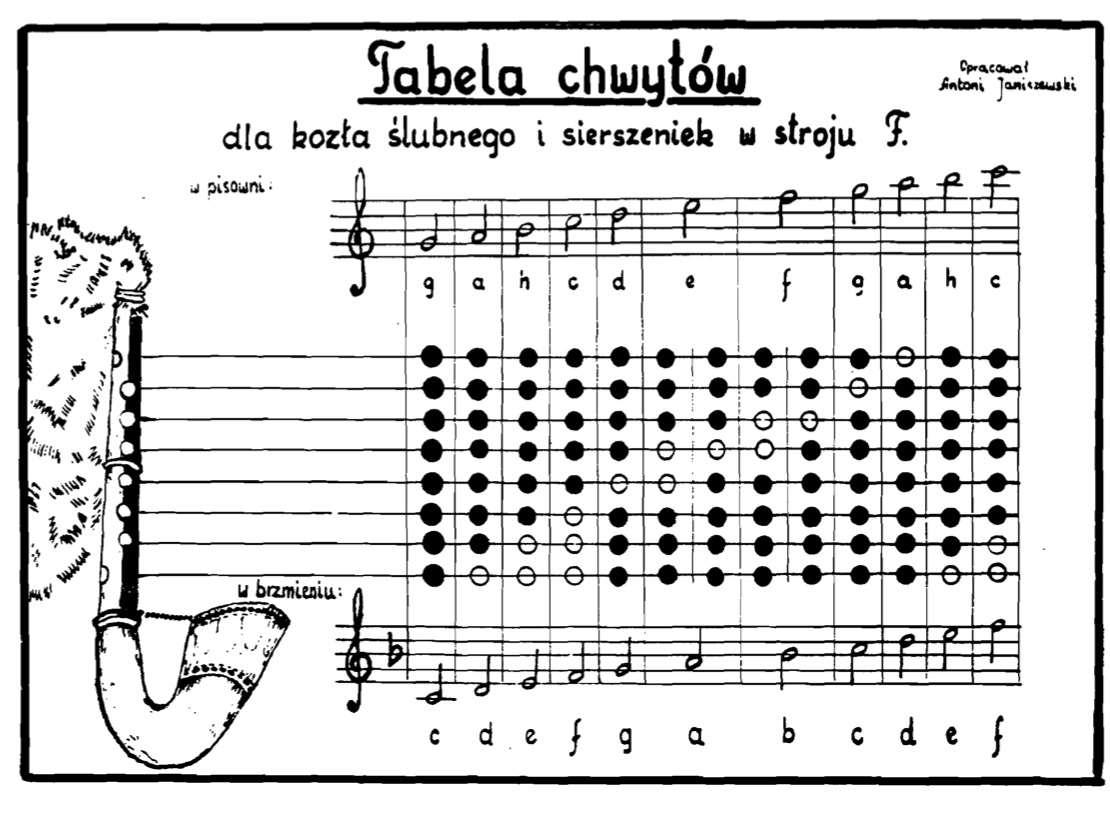

It is traditional for the Dudy and Koza to be played at village social events, sometimes in duo, and sometimes accompanied by clarinet, fiddle, or vocals. In Poland the Koza SJubnego is a black-bagged pipe played before a wedding while the Koza Weselnego, a white-bagged pipe, is used during or after the wedding. Thesepipes are capable of over-blowing two notes which yields a range of an eleventh. It is no surprise to learn that the playing and making of these pipes has been preserved by the “Highlanders” of the respective regions. Access to information on Czech and Polish pipes has been facilitated by the writings of Josef Rezny and AntoninJaniszewski, respectively. Two very active players of Polish pipes in the United States are Sean Folsom and Rik Palieri (see the interview with Rik in this Journal). Below is a fingering table (by A. Janiszewski) for the Polish bellows-blown wedding pipe called Koza Siubnego and for its practice chanter pipe (mouth blown, akin to the concept of the Scottish “goose”).

27

CARE AND MAINTENANCE OF BELLOWS-BLOWN BAGPIPES By Michael MacHarg

Your Editor and Chairman of the N.A.A.L.B.P. has asked me to write a short article for the Journal concerning the care and maintenance of all the lowland bellows pipes.

No matter how you received your set of pipes ergo, by return post or collecting them in-person from the makers shop, examine the pipes generally for any obvious problems such as loose mounts, slack hemp joints as well as joints that are too tight. Check also that all the stocks are secure in the bag and that all the valves, blowstick and bellows are working properly. Make sure the reeds are in good working order and that they have not fallen out of the reed seats into the bag.

If this is a used instrument, but new to you. all of the above applies to this set as well. I would give a used instrument a complete overhaul, that is, completely checking the bag for airtightness as well as the stocks for loose ferrules, cracks, etc. Try to turn any or all of the stocks in the bag to be sure that they are well tied-in. You cannot tolerate even a small air leak from the bag, or for that matter from any part of a set of pipes, be it drone stocks, sliders, reeds, etc. It has to operate as a fully pressurized system.

Seasoning the pipe bag and in some cases the bellows is necessary to render them airtight. Which seasoning to use? Do not use Scottish highland pipe seasoning as it contains ingredients not harmonious to dry blown reeds as some contain water. If you must season your bag and/or bellows you can make a mixture of olive, neatsfoot or sweet almond oil and bees wax in equal parts. This is made in a double boiler set-up so as not to risk a wax or oil fire, and is applied quite warm to bag and bellows. How often should this be done? There is no hard and fast rule. I would say when your bag is having difficulties holding air or the bellows is not drawing well, it’s time to season.

The sound in general and the overall performance of the instrument is greatly enhanced by oiling the bores of the drones and chanter. All of the stocks and other connections should be oiled as well, but not as frequently as the other musical parts. Traditionally olive oil is used for oiling the pipe parts, although a number of different oils can or are being used such as sweet-oil (medical grade oil), almond oil, sweet almond, and various commercially available bore oils. One should continue to use the oil that was first used on a particular set of pipes. I don’t think using 2 dissimilar oils is a good idea, although no great harm will be done if this happens. I personally prefer sweet almond oil as it is more refined than other oils (thinner), will be absorbed by the wood easily and will not leave a residue after prolonged use. Almond oil has been used on wooden musical instruments for hundreds of years.

28

I personally do not use oil on the outside of a set of pipes, except when used as a finish or polish (a completely different type of oil). One may use oil on the outside of the pipes, if they wish, as it will not harm the wood or other parts or mountings.

Preparing the joints is a topic which is not often addressed or taught. There are a few basic things to be aware of in re-hemping your pipe joints:

- Whatever cord you use, it should not be too large in diameter or too coarse texture and should be able to hold wax.

- The cord should adhere to the combed recess of the section being re hemped. This is accomplished by coating the first 12″-24″ of the cord (hemp) with black wax (Thermawax or Healball) and proceed to wind the joint rather firmly.

- When the joint is wound to an easy sliding fit, the surface should be rubbed with bees wax and smeared into the cord with the fingers.

- Teflon tape may be added at this stage if you like (non-traditional) as it works quite well. When using teflon tape, you must put bees wax on the joint (cord) first, or the tape will not adhere and will slide off.

- Important: try to avoid wrapping a little bit of hemp onto a joint when it is loose to make it tight (firm). Again, many stock and drone sections have been damaged (cracked) using this quick fix method. If the joint is too slack or loose, rewrap the entire joint.

Pipe bags do have to be replaced from time to time, because they are getting old and are not airtight anymore. In the case of a used instrument it may be too large or small or not the correct shape (style) for you. Many seasoned pipers will not tie-in a pipe bag, as they have not been taught to do so, or are just intimidated by the whole procedure. If you are happy with your old stock positions in the bag, simply transfer the stock locations to the new bag. Refer to the College of Piping Tutor #2 for the basic method, or contact your local pipe maker and I’m sure he or she would be happy to tie-on a new pipe bag for you for a small fee.

If you have further technical questions, feel free to write to Brian or me – we will do what we can to help.

Mike MacHarg RFD 2, Route 14, Box 286 South Royalton, Vermont 05068

29

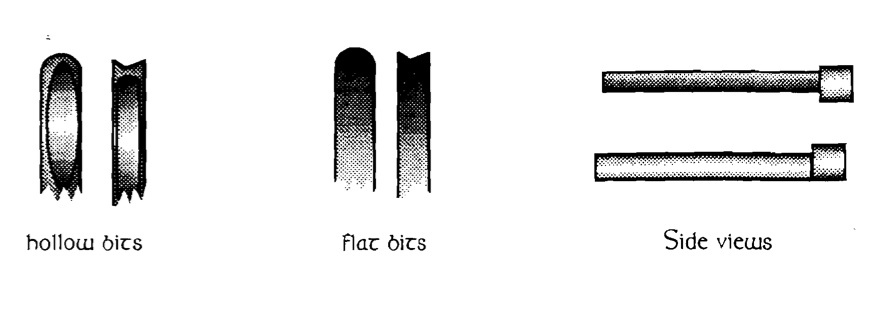

A BORING ARTICLE By Eoghan Ballard

When two or more pipesmakers get together. the talk quickly moves from the making of music to the making of bagpipes. What topic do you expect would enthrall a group of pipesmakers? Woods? Finishes? Measurements? ln this day and age, – ivory substitutes? The latest jigs and new tools? Antique tools and methods of manufacture? All these and more. One topic that seldom takes up a lot of time in these discussions is that of drill bits. Little attention seems to be paid to them. Perhaps they are considered too basic, or a closed subject”. That is unfortunate for they are neither.

There may be more exciting issues to discuss. None the less, if the bore is not drilled accurately and cleanly, the new instrument will likely get no further than the lathe. If it does, it may not be worth the materials from which its made.

The manufacture of pipes requires a respectable variety of good quality drill bits. This is essential. A less than perfect lathe can be dealt with; a set of turning tools made From old files will hold the requisite edge. drill bits that are less than adequate will haunt the hopeful pipesmaker as long as they’re tolerated. These drills should represent a good range of sizes from machinist’s numbered bits up up to bits several inches in diameter. Lengths will vary from less than an inch to over a foot. The types also vary. A good collection may include spoon bits. aircraft bits, shell augurs, twist drills. brad drills. even spade bits. What should not vary is the quality of the steel. High speed tool steel is what should be sought. While I do not suggest that the only good bits should cost top dollar, be cautious when faced with a deal that seems too good to be true. It often is.

For drilling the finger holes. average length bits are sufficient for the job. You may use machinists bits, though brad point bits are my preference. They seem to

30

cause less tear in all but the hardest woods. While highspeed steel will be enough to make any pipesmaker proud, if you can afford carbide tipped blades, they will stay sharp far longer. What kind of cost difference is there? A set of 100 high speed bits may run as much as $200.00. By comparison, a set of only 7 carbide tipped bits might sell for $75.00. Do not feel however that cost should keep you out of the field. Bargain hunting is enjoyable, and there is nothing wrong with buying inexpensive tools so long as you look for reasonable quality, and price does not always equal quality!

Turning our attention to the drills used to bore out the chanter and drones, we are met with a far less easy set of choices. This is where resourcefulness comes in handy. Short drill bits are readily available, and while some may be quite costly, there is such a variety that reasonably priced alternatives may be found. When looking for extra long drill bits, the absence of appropriate bits is immediately obvious.

If your pipesmaking endeavors are going to be restricted to smallpipes, then you will be less challenged in this area than will be the individual who wishes to a make set of Uilleann pipes or even a set of Lowland Pipes. With Smallpipes, a 10inch long drill is probably adequate, especially with the Scottish varieties. For this type of task, invest in a set of long brad point bits from a fine woodworking tool catalog. Expect to pay as much as $10.00 apiece FOR these bits. You may locate a set of them for as low as $20.00 to $30.00. but, the narrower ones (the most critical for our purposes) are likely to be Faulty. Having gotten these: Drill slowly! I do mean slowly. There are those who prefer to drill at high speed. With practice and some of the bits I shall describe later this may be done. The rate at which drill bits come out the side of a piece of wood in the early stages of learning is such that I suggest going slowly at first. It allows time o check on progress. While you are not going to be making any mistakes, it is pleasant to observe perfection at a leisurely pace.

31

Uilleann pipes or Lowland pipes require a different strategy. Once upon a time it was easy. WoodCraft used ta sell Ridgway Shell Augurs. They could be got in lengths of about 24 inches and in a healthy variety of widths. I am unaware of anyone who currently sells chem. A call to WoodCraft might result in a lead. Here is where creativity comes in. Several alternatives exist to suite different tastes.

The wood may be drilled halfway, rechucked in reverse and drilled so that the holes meet. in the Center. They seldom do, even with care. Using a great deal of care, and wood, this method can be made to work – some of the time. A drill can be lengthened by brazing a long rod onto it. Alternately, homemade drills may be manufactured. If you choose this path there are several types of bits that may be made. Buy good drill stock in lengths suitable to your need. If you have some smithing skill, you may want to upset the end to be used for the cutting edge so as to make it somewhat wider than the shank of the drill. This isn’t essential but it aids in clearing wood chips when boring. The alternatives now are to make a square end or Round end spoon or shell augur (hollow), or a flat ended bit.

A small grinder such as used by hobbyists may be utilized to do the shaping. Grind slowly to avoid overheating the metal. Care must be taken to temper the bit correctly. The lifespan of your tool is determined in large part by how the metal is tempered. To hard and it will be brittle. Too soft and it will wear down too quickly or bend. While this article cannot go into the intricacies of tempering steel, the best color for a bit is a rich peacock. That is a deep purple color. Today there are several excellent books on toolmaking written with the Woodworker in mind.

32

Experiment and share you results. Patrick Hennelly, the Chicago pipesmaker, once told me that there were no such things as trade secrets, only fools who thought they had them. Spoon bits or shell augus will allow for faster speeds to be used when drilling than do twist drills. Twist drills have a greater tendency to wander with the grain. I still recommend thatyou stick with Slower speeds, but that is a personal preference.

lf you can come across them. there is one other alternative. This drill bit is a gun makers drill. It is similar to a shell augur with an angled rather than rounded tip. What sets it apart is that itvhas one or two small bores running the length of the bit. lf hooked up to an airorush style compressor that can push air through the bit, this kind of bit will allow for fast, clean and cool boring. I’ve seen them in use by the late Johnnie Burke of Bra,. Co. Wicklow. He mounted a small compressor to the tail stock of his lathe and sworee these bits cut ebony like butter.

33

ACOUSTICAL ASPECTS OF BAGPIPE CHANTERS by Brian E. McCandless

The following article is based on the first half of a lecture entitled “A Millenium of Bagpiping in the British Isles and Ireland” written by Brian McCandless in 1992. He presented it at the 1992 convention of the Mid-A tlantic Chapter of the Society of Ethnomusicology at the University of Pennsylvania on April 11, 1992 with musical assistance from Michele McCandless and Mike MacNintch. A short form of the talk was given as a workshop at the 9th Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention at North Hero, Vermont on August 28, 1993. The text of the historical section of the talk will be presented in Journal 7 along with some rare illustrations showing some connections between British-Irish piping traditions and those from continental Europe. There is a lot to understand here, so I recommend you read Arthur Benade’s “Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics,” 1976 (reprinted in 1990 by Dover Publications) for more detail of woodwind instrument acoustics. I would like to thank Sam Grier and Peter Riley for sharing their own findings with me. The subject of how a reed vibrates and how it responds to the shape and geometry of its stock is complex and deserves its own article. Let us suffice it to say that a chanter reed works by the interaction between air pressure (the force compressing the reed blades) and elasticity (the reactive force of the reed blades). There is a strong modulating component caused by the air flow through the reed (Bernoulli effect). The ensuing oscillations in airpressure occur many times per second and are the driving force of any reed.

The untamed reed, whether a blade of grass held between the thumbs or an oboe reed fashioned precisely from paper-thin strips of cane tied onto a metal staple, is an unwieldy device, vibrating freely and generally disturbing the atmosphere as air is forced through it. Place this device so that it feeds into a cavity or chamber, however, and two things happen. First, the air displaced by the reed expands to fill the cavity and eventually exits. Second, the time-oscillating pressure produced by the reed will result in a series of standing waves within the chamber. These standing waves are said to “resonate” thereby producing an audible tone whose character and volume will depend on the shape and size of the cavity and on the vibrational properties of the reed feeding it. If few well defined standing waves are established, then no distinct tone will be detected, but rather, a buzz will be produced. If two standing waves cancel each other out, then no sound is emitted. Some places within the cavity will have very low wave intensity – these points are called nodes.

When the cavity and the reed are well matched, a rich harmonic spectrum is set up within the cavity which allows for a wide range of tonal possibilities at different points within the cavity (like in an ocarina). If the cavity is long and thin, e.g., a tube, the tone obtained will be a strong function of the tube’s length. If we perforate the tube at some point along its length, we disrupt the natural harmonics of the tube and effectively shorten it, which raises the pitch. The pitch raises because higher tones are produced by higher frequency harmonics and these are produced by shorter tubes. Lower tones are produced by longer tubes, which can resonate at lower frequencies. Thus, fingering a chanter changes its length and therefore its pitch. Subtleties of fingering, such as cross-fingered notes and forked fingering can be used to flatten a note one semitone or to improve the tone color and intonation. These techniques are the basis for vibrato and systems of codified playing throughout the bagpipe world.

34

Bagpipe chanters, oboes, clarinets, and the like are perforated cavities which are well matched to specific reeds. Within the limits of acoustical practicality, the dimensions of the instrument – length, taper, finger hole position, finger hole size, and wall thickness – are configured to meet the musical demands placed on the instrument. It is a matter for history to decide which came first for any given bagpipe – its chanter design or its reed – but many of us feel that for each class of instrument there exists an archetypal reed around which many variants of a given instrument may be designed. It may surprise some of you to learn that the same cane or plastic chanter reed fitted into a Northumbrian small pipe chanter in F will perform equally well in a Scottish smallpipe chanter in D. This is because the popular designs for these chanters call for the same cylindrical bore, with a diameter of around 3.4 mm (11/64 inch). If you line up the reed seats of these two chanters, you will find that within nominal tolerances, the holes of overlapping scale notes (G, A, C#, and D) are in the same position along the length from the reed seat.

In fact, there is no theoretical reason why a chanter with a cylindrical bore cannot be made in any musical key to fit a single reed design by simply changing the chanter length and positioning the holes correctly for the chanter scale. The limits to this logic, however, are chanters too short or too long to be practical for fingering. Also, the reed design must be such that it can drive a long chanter (A or low G) without shutting off due to the higher acoustical impedance. To balance the dynamics (volume) of the chanter notes, the finger hole size and depth must be adjusted to compensate for varying acoustical pressure inside the chanter along its length. For example, consider a chanter-reed combination that is rich in higher order harmonics. If all the finger holes were the same dimension in such a chanter, then the upper notes would sound louder than the lower notes. To compensate, the upper holes must be reduced in size relative to the lower holes. Also, if a fingerhole is located near a node, then it must be enlarged or even re-positioned to increase its volume. In some cases the neighboring hole down the chanter may have to be adjusted to improve the dynamics of the chanter. Naturally, there are limits to the range of finger hole size – too large and the chanter is foreshortened, too small and the hole has no effect. A general rule is that finger holes larger than the bore diameter offer no advantage, while the minimum diameter is determined by the fundamental frequency it needs to admit and the chanter wall thickness, which adds acoustical impedance. It is of interest to note that a small crack in a Scottish smallpipe chanter may not affect its intonation at all and would only produce an audible buzz as the sides of the crack rattle together.

In another example, the French folk musette pitched in G takes the same reed as the classical oboe pitched in D. Only minor reed adjustments are required to make the reed work effectively in both instruments, despite the very different lengths of the instruments. Again, like the smallpipes, the oboes have the same bore profile, but in this case it is tapered from a narrow reed seat to a wide bell. The bores in these instruments follow a conical geometry whose cross-section yields a total enclosed angle (or bore angle) of 1.5 degrees. The narrow bore angle facilitates overblowing with true intonation. That is, each finger hole must perform two jobs – it must be in tune at two different pressures.

35

Double toning is a joint effort on the part of the reed and the chanter. The reed must be forced into a higher vibrational mode and the chanter must be able to support the second order resonances. Now single-bladed reed instruments like clarinets and saxophones overblow a twelfth so that metal keys are required to produce a regular scale. Double-bladed reed instruments, however, overblow an octave so that a continuous scale through two or three octaves is possible with similar fingering in both octaves. With an oboe or bombarde, the player increases both the air pressure and the embouchure pressure to effect the jump to second octave. A tiny hole located close to the reed seat, vented with a metal key, may be used to disrupt the first harmonic mode, facilitating the jump. Such a key is called a register key. With a border pipe or pastoral pipe there is no embouchure possible nor is there a register key. Overblowing is accomplished by increasing the bag pressure and (in some cases) simultaneously pinching the thumbhole with the thumbnail, a technique called “shivering the back lill” in Scotland. On an uillean pipe chanter the jump is facilitated by closing the chanter on the knee and increasing the bag pressure. The excess bag pressure sends the reed into its higher vibrational mode when a finger hole is opened or “vented”.

It is easy to prevent a chanter from overblowing. From a design perspective, conditions which restrict second harmonic standing waves will limit second octave possibilities: stiff reed, soft wood, rough bore, and narrow bore angle are examples of such conditions. From this list, only the bore angle uniquely establishes the chanter’s range in the second octave – too narrow and the overblown notes are little more than a squawk, too wide and only a few notes over the octave are possible. Over these past years I have collected measurements of conically bored chanters and have found that the instruments can be classified according to their internal bore taper. This critical dimension not only determines the number of notes over the octave which one can obtain but it also contributes to the tone and volume of the chanter because of the frequency and intensity of the standing waves it permits. Below I offer a table of bore tapers I have measured from numerous instruments and plans.

36

A simple geometrical system for remembering two commonly used bore tapers was taught to me by Sam Grier. For a pastoral or narrow bored uillean chanter (~ 1.2 degrees), use the taper angle formed by a trapezoid 12 inches long, 1/2 inch at its wide end, and 1/4 inch at its narrow end. For a lowland or border chanter (1.8 degrees), use the taper of a trapezoid 12 inches long, 1/2 inch at its wide end, and 1/8 inch at its narrow end. These dimensions are used to produce reamers of the desired taper angle. The minimum dimension is fixed within the chanter by the “throat” diameter dictated by the reed. To actually produce tapers in chanters, makers step-bore the wood on a lathe and then remove the steps and polish the bore smooth to the desired angle with the reamer. There are several kinds of reamers which can be used in chanter fabrication: spade reamers made from flat stock, “d” reamers made from ground round stock, and fluted reamers. I have also seen reamers made from files, hacksaw blades, and French bayonets.

When reeding conically-bored chanters, it is important that the missing volume of the cone at the end of the chanter equal the internal volume of the reed and staple. This is because the reed occupies a node of the oscillating chanter and its geometry and dimension need to correspond to the missing chanter cone as much as possible. Given this guideline, the reed and chanter loudness and clarity will be affected by the shape and extent of the staple opening inside the reed.

Some final aspects of bagpipe chanters worth discussing are the finger holes and the geometry of the end of the chanter. Aside from their obvious role in determining intonation and volume, the finger holes can also produce excessive turbulence within the chanter, particularly when the chanter is made from a hardwood and the holes have sharp edges. This problem is worse on higher pressure instruments such as border pipes and highland pipes and can produce a variety of effects, from tuning sensitivity of each note to an unsavory grating sound. The cure is to round off the finger holes – both where they penetrate the chanter bore and along the outside. What is desired for the least turbulence, hence most clear tone, are tone holes that have “rounded corners” – completely smoothed after drilling. Finally, the end of the chanter plays a small role in controlling the tone of the bell note and super bell note since the chanter end is another node of the fundamental vibration. Some instruments, such as the Northumbrian smallpipe, are closed, in which case the node is occupied by a hard object. This can produce a sound that is too brash and is corrected by the addition of some cotton in the chanter end to dampen high frequency oscillations. On open-ended chanters the shape of the terminus is more important. The right flare can add high frequencies to the chanter tone, as these penetrate the flare farther than the lower frequencies, which are reflected back into the chanter as part of the standing wave. This effect is most noticeable on the bombarde, where the bell is located very close to the keynote of the instrument. Instruments with narrow tapers or long bodies past the lowest finger hole or tone hole are only slightly affected by the shape of the terminus.

37

AN INTERVIEW WITH RIK PALIERI A Player of Polish Bellows Pipes

In May 1993, on his way to a week long musical event in North Carolina, Rik Palieri from Vermont stopped in at the home of Brian and Michele McCandless for an over night visit and to talk about the bellows-blown bagpipes of Poland. Bellows pipes of Poland, you say? Yes it is true that bellows-blown bagpipes are found in eastern Europe. Rik Palieri is one of the few Americans who have sincerely taken up the performance of this instrument. In his studies he has traveled to various parts of Poland, particularly to Istebna to meet with makers and players, and to actually learn from old masters the art of playing the Polish bagpipes and to use them in performance with song. During his stay at the McCandless household, Rik related the following detailed story about his involvement in Polish bagpiping. We have tried to be as accurate as possible with the spelling of Polish names and places. In cases where we think we have erred, we have been faithful to the phonetic equivalent.