To download the original scanned Journal as a pdf please click here.

JOURNAL

OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 1991

CONTENTS

QUOTATION PAGE………………………………………………………………………… 2

EDITORIALS………………………………………………………………………………….3

LETTERS…………………………………………………………………………………….. 4

PIPE DREAM COME TRUE by Mike MacNintch…………………………………. 7

ANTIQUE BELLOWS PIPES by Alan Jones………………………………………..9

REEL, CHAMBER AND PASTORAL PIPES by Sam Grier…………………….12

TOWN PIPERS – A EUROPEAN CONTINUITY by Brian McCandless ……18

THE BAG IN OUR BAGPIPES by Mike MacHarg ……………………………….27

WHAT JOCKEY SAID TO JENNY AND OTHER LYRICAL ILLUMINATIONS

ON LOWLAND PIPE MUSIC by Brian McCandless ……………………………30

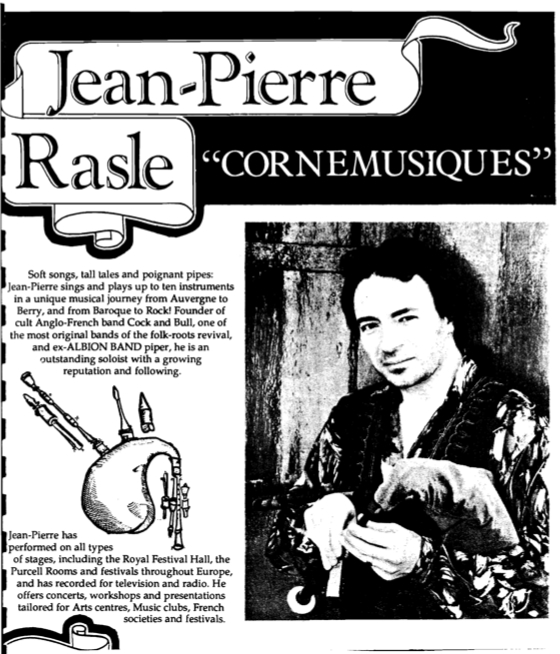

PROFILE – Jean-pierre Rasle……………………………………………………….. 38

REVIEW:

NORTHUMBRIAN PIPING CONVENTION

AT NORTH HERO, VERMONT 1990………………………………………………. 40

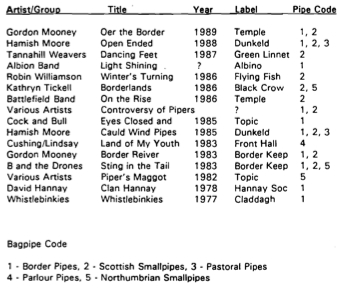

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY………………………………………………………… 42

TUNES……………………………………………………………………………………….43

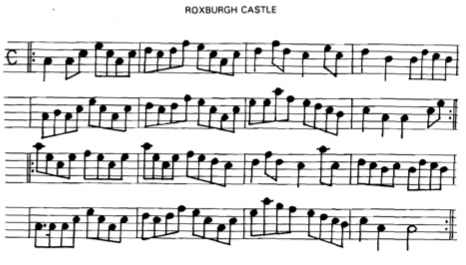

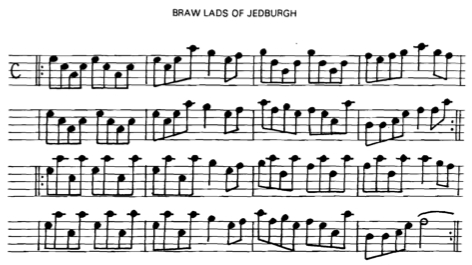

– Roxburgh Castle and Braw Lads Of Jedburgh…………………………………44

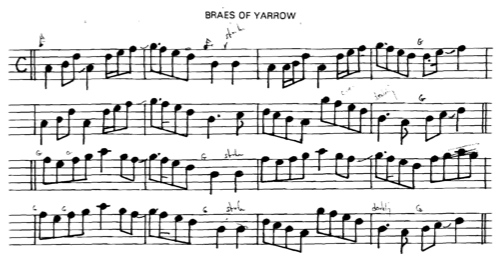

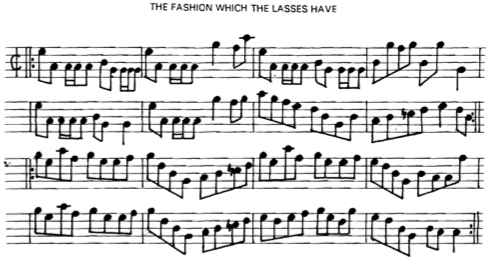

– Braes of Yarrow and The Fashion the Lasses Have ……………………… 45

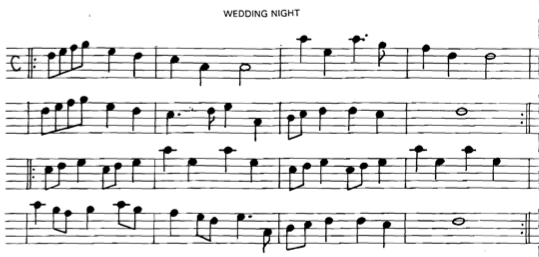

– Wedding Night and Goddesses ………………………………………………….. 46

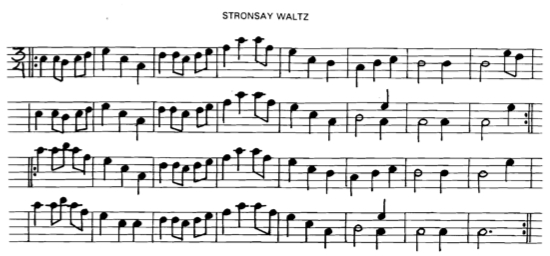

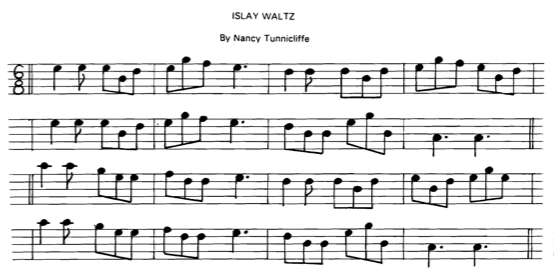

– Stronsay Waltz and Islay Waltz…………………………………………………… 47

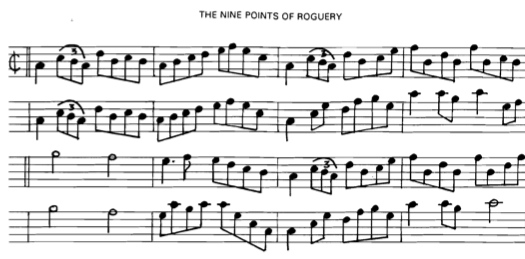

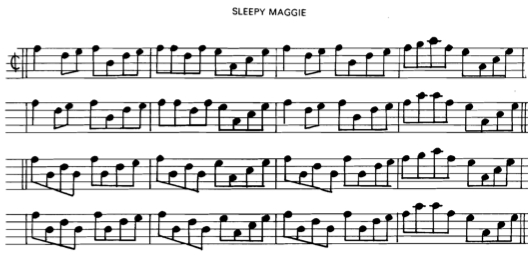

– Nine Points of Roguery + Sleepy Maggie ……………………………………… 48

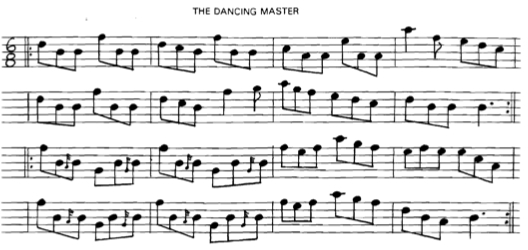

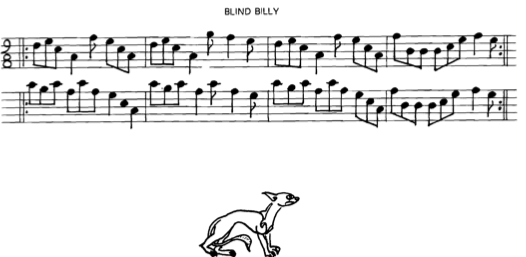

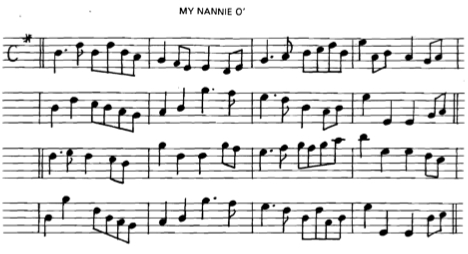

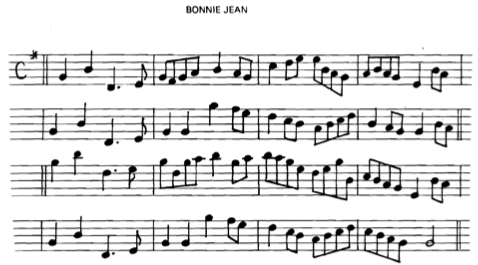

– The Dancing Master and Blind Billy ……………………………………………… 49

– My Nannie 0′ and Bonnie Jean ……………………………………………………. 50

CALENDAR………………………………………………………………………………….51

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS……………………………………………………52

BAGPIPE MAKERS AND PIPING SUPPLIERS…………………………………. 53

REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………. 54

MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION………………………………………………………. 55

1

QUOTATION PAGE

ON LOWLAND PIPE GRACING

” …articulation of the notes of the scale staccato, a feat impossible with the open-ended chanter, where, the wind-stream being unbroken, the sound is continuous and the repetition of a note can only be suggested by means of intervening grace-notes or ‘cuttings’ between the note and its repetition. The Scottish Border small-pipes have the usual open-ended chanter. In the Highland pipe technique these ‘cuttings’ referred to are highly conventionalized and the piper conforms to them very strictly: but according to Joseph MacDonald there were no such standardized patterns of grace-notes in the

Lowland techniques.”

From The Traditional and National Music of Scotland by Francis Collinson, Vanderbilt University Press, 1966.

VERSE

“0 Logie of Buchan, 0 Logie the Laird,

They hae ta’en awa Jamie that delv’d in-the yard,

Wha play’d on the pipe and the viol sae sma’,

They hae ta’en awa Jamie, the flow’r 0′ them a’.”

From “Logie 0′ Buchan”, an old Scots song, possibly composed by Lady Ann Lindsay (1750-1812?), authoress of “Auld Robin Gray”, eldest daughter of James, Earl of Balcarras, by his Countess, Ann Darymple, daughter of Sir Robert Darymple of Castletoun, Bart. Source: 1853 Edition of James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum.

A BLAST FROM THE PAST

- Yet such an enthusiastic Scotchman as Sir John Graham Dalyell [1783] writes as follows: – “The Lowland bagpipe of Scotland may be apparently identified with the Northumbrian; but it is viewed rather contemptuously by the admirers of the warlike bagpipe, because its music merely imitates ‘the music of other instruments’ – meaning that it is not devoted to perform what they deem the criterion of perfection, the piobrach [sic].

- Dalyell, in his observation as to the identity of the Lowland and the Northumbrian pipes, is fairly correct, but he fails to notice that both instruments are clearly borrowed from the Irish Uillean pipes. In fact, it may be taken for granted that the only difference between the Lowland and the Northumbrian pipes is one of size, the Northumbrian being the smaller.”

From The Story of the Bagpipe by Grattan Flood, Walter Scott Publishing Co., 1911.

2

EDITORIALS

TO JOIN OR NOT TO JOIN?

“Should I join this Association, or the one in Great Britain?” is a question that has been asked by many prospective members of the NAALBP since its formation. The answer to this question is really quite simple: join both! What better way could there be to learn more about cauld wind piping? Each organization offers different publications with very different information. It is an ideal way to stay well-informed.

In addition to this organization and the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society there are several other groups you may want to join. Very often, facts concerning one kind of bagpipe pertain to others. The addresses are listed in the Reference section of this issue. Allow me to highly recommend The Bagpipe Society to anyone who is even remotely interested in any kind of bagpipe. I strongly encourage our members to join

other groups and to become active in our own.

– Mike MacNintch

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

I am delighted at the response we’ve received to our Association in the past year, particularly after issuance of Journal Number 1. Our membership is healthy, and written contributions are coming in – it is great to have several items already lined up for Number 3, with Number 2 just completed. Send us more! Your letters are important as they indicate that there is activity and thought on the topics we present. If you

are research-inclined, I’d like to suggest two topics for future articles:

– stories of Lowland pipers in the Americas prior to the 1970’s. Since we have beaucoup evidence of instruments afoot in North America since about 1780, there ought to be tales of the players. I suggest the local columns of old newspapers, specialty sections of magazines, and of course, any old Scottish-American

or Irish-American literature. For example, in O’Neill’s Irish Minstrels and Musicians (1913) there is a reference to one Joseph Cant who “Occasionally…turns out a new set of pipes – the half size reel set with [common] stock and bellows being his favorite” .

– photographs of Lowland and Border pipes in museums, in old museum collection description books, and in old music books. Get out your high speed black and white film and your macro lens and get over to the library!

Finally, please take notice of the increased membership fee. This is to cover our publication and postage costs, which are higher than we anticipated.

– Brian E. McCandless

3

LETTERS

Cross-Breed Border Pipe

Although I am mainly a Northumbrian smallpipe player, I have enclosed a photograph of some Border pipes that I have pieced together over the years. The drones, two tenors and one bass were made by Mark Cushing. The stock and bellows are by David Quinn. The chanter is from a Highland pipe – I turned the ends down to suit the stock and overall tone of this type of instrument. I found it necessary, however, to construct proper reeds for the drones and chanter as these were pitched around C#. If anyone needs drone reeds and bags to suit Northumbrian smallpipes or other cauld wind pipes, please contact:

Bradley M. Angus

Jacksonwald, PA

Offer of Assistance

Dear Sir:

As a long standing member of the Lowland and Border Pipers Society, I would be happy to help you and your members in acquiring instruments and/or accessories to enable you to function as a Group. I am at present manufacturing sets of Highland/Lowland pipes and Gaitas and would be pleased to assist with any of your piping requirements.

With best wishes to you and your Society.

lain MacDonald

PM Neilston and District Pipe Band

Glasgow G78 3NB

4

LETTERS (continued)

Corrections on “Recollections…”

Dear Sir,

I read the article by Sam Grier with some surprise in a recent issue of your journal. His claim that my Uncle Archie MacNeill was “a bellows smallpipe player” is quite false. To my certain knowledge Archie never played a bellows pipe in his life, so it is totally impossible for him to have, as it is claimed, “taught many people something of smallpipes.” Mr. Grier’s knowledge of Archie’s abilities and of his history is surely a little bit confused. His remark “in later years after losing his sight” gives the show away, because Archie was totally blind by the age of twenty.

Nor did he tour the Highland Games as is claimed. He competed once or twice certainly, but his blindness was an impossible handicap for going round the regular circuit.

Mr. Grier’s memory of “Highland pipers playing Ceol Beag and Ceol Mor like fiddlers” is Quite misleading. My memory of piping in Scotland goes back much further than his and at no time did I ever hear pipers – other than tinkers – play anything but the standard music to the best of their ability.

The one statement which I do agree with him on is that my cousin Alex was a better piper than me. The remark about Alex’s “Father’s smallpipes with the 4-keyed chanter” is an example of something not too well remembered. Archie never owned a smallpipe but he did own a 4-keyed chanter – one of the Brien Boru ones. This is played, as you are probably well aware, in the Highland pipe and gives two notes above high A and two notes below low G. The Quality of the music is dreadful and Archie’s wife used to refer to the instrument as “the bull”.

In the years before he died Archie dictated his memoirs, not to be published until after his death. I hope to put these into the Piping Times in the near future, now that the chance of being sued for defamation must almost have disappeared.

Yours Sincerely,

Seumas MacNeill

Mr. Grier Replies

I should like to thank Seumas MacNeill for setting the record straight. It seems I do have considerable “egg on my face”. I was advised that Archie played bellows pipes with a four key chanter, and also chamber pipes with ceilidh type dance bands. if it was a Brian Boru pipe chanter, I must agree with his wife it is rather atrocious sounding although the Brian Boru practice chanter in B flat does sound rather good, but it

is impossible to play a birl on it and so it loses much character.

My understanding was that, as a boy and young man, Archie did tour Highland games when he could and was very much infatuated by the leading pipers of the time. I believe he did want to compete as he grew up, but of course other powers intervened.

When I mentioned pipers playing like fiddlers, I said Ceol Beag and Ceol Meadenach, not Ceol Mor. That is of course the classical original art of the Highland Bagpipe. The pipers I was referring to did play quite correctly and for the most part were considered as experts, generally playing at ceilidhs after the games, and in various pub circumstances. Many were Pipe Majors and did play very relaxed and very musical, as do many competent fiddlers and other instrumentalists. I am happy to hear such very talented pipers as those who are currently playing with the many top [folk] groups who bring good piping to many people who would otherwise not be in a situation to hear the instrument played. This can only be a good thing.

I should like expressly to apologize to Seumas for any comparison between himself and Alex. It was unkind, inconsiderate, and quite unnecessary. There are no doubt times when I should be listening, and not talking. I am very sorry. (continued)

5

LETTERS (continued)

For the record, and the readership, I must say that I have only the greatest respect and admiration for Seumas MacNeill. His work in the College of Piping and his editorship of the Piping Times stands as a contribution to Highland Piping which could only be equaled by his uncle Archie. His recordings, particularly the one called “Piobaireachd”, if I’ve spelled it correctly, have always been very much admired by myself.

I believe Seumas and I have only met on one occasion. At the residence of my good friend Kennie McKenna of Montreal. If I remember it right, it was around 1965 or so. I was in the company of Dr. Ronald Sutherland of North Hatly, Quebec, and Wendall Maclean, of Montreal. I was introduced as the Pipe Major of the 24th Technical Squadron, R.C.E.M.E., of Sherbrooke, Quebec. It was very much an honour to meet you at the time and it remains so. I have always admired your Uncle, and look forward to your publication of his memoirs.

Yours Truly,

Sam Grier

Greenville, S.C.

Pastoral Wooings

Dear Sir,

There is nothing quite so special as playing my smallpipes under the protective canopy of the elm trees which surround the grassy glade of my home. The cool breeze drifts lazily down through the soft giant boughs and mingles with the delicate notes of my chanter as she sings her sweet tunes, unchallenged by the birds of the forest. Just as the moss blankets the forest floor so the drones create a gentle covering on which my tunes are laid. The trunks of these old trees do quiver ever so slightly as they resound with the echoes of the melody. The whole effect is really quite pleasing, and I thought you should know.

Yours truly,

Dusty Landon

Cherrydale

6

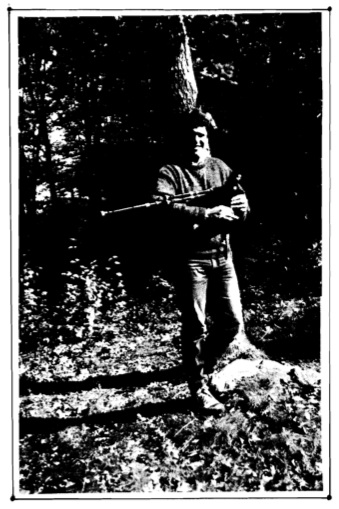

PIPE DREAM COME TRUE by Michael MacNintch

It all began a few years ago, when I first convinced Tom Childs to go to the Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention in North Hero, Vermont, for that is where he bought his first set of Scottish smallpipes. After having had smallpipes literally “waved under his nose” for a couple of years, Tom became hooked on “cauld wind piping”.

Being a fine Highland piper, Tom had restored several old sets of Highland pipes to good playing order.Naturally, as his thoughts turned to bellows pipes he was often heard to say “I would love to fix up an old set of Border pipes!” He even wrote away to the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society and asked if it was possible to find an old set. The answer he received as realistic and apologetic… “wouldn’t we ID.! like to find an old set!”

But then one night last May I received a frantic phone call from Tom. He was almost incoherent, and when he slowed down, he said “You’ll never guess… ” He had just made arrangements to purchase an antique set of Border pipes!

The story went like this. Tom had been playing at a Scottish function when an older gentleman approached him and asked if he knew anyone who wanted to buy pipes. The man said that he had a couple of Highland sets, some Irish pipes, and some Northumbrian pipes. Tom was intrigued but played down his interest and casually took the man’s number. Later he recalled “I counted the days, hours, and minutes until I was able to call this man” [see Alan Jones’ article for a similar incident],

Upon visiting the man, who happened to be an antique dealer, Tom was forced to hear a hour long speech concerning the restoration of antique clocks. The whole time the various pipes were in full sight, and Tom could plainly see that there was a set of Border pipes on the table. “My eyes were bulging clean out of my head”, says Tom. The pipes were ivory mounted blackwood! The bag was shot and there was no chanter, but the rest of the instrument was in fantastic shape. At first Tom did not expect to be able to afford them, but it turned out that the man only wanted hat he had paid for them back in the fifties.

About three weeks later, Tom returned and paid for a regular treasure trove – the Border pipes, two Uillean pipe chanters (one a double chanter with keys), and a bellows. There was also a “thing” that appeared to be a drone-end which was converted into a chanter, quite unsuccessfully.

At the 1990 Northumbrian Pipers’ Convention Tom showed the pipes to both Gordon Mooney and to Sam Grier. Both agreed that the pipes were from the period between 1760 and 1820, the Regency period, and that they were a typical Border set.

Tom soon enlisted the expert services of Mike MacHarg for a new bag and chanter. The rather nice piece of yellowed ivory at the end of the “thing” became the sole for the new chanter – it matches the drone mounts very well. The bellows have yet to be restored, but the pipes are going well and play near A.

Tom’s experience should serve as lesson to us all – that those pipe dreams can come true. As Mike MacHarg said, Tom is one of those people who can fall in a vat of mud and still come up grinning, for this isn’t Tom’s first lucky experience. We can all hope that one day our chance to make a rare find will come along. Lately, Tom has been talking quite a lot about Pastoral pipes…

7

Tom Childs playing his restored Border pipes.

Tom Childs playing his restored Border pipes.

8

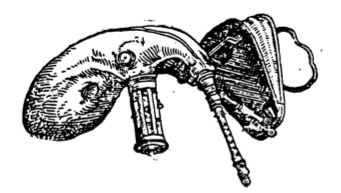

ANTIQUE BELLOWS PIPES by Alan Jones

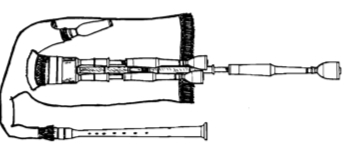

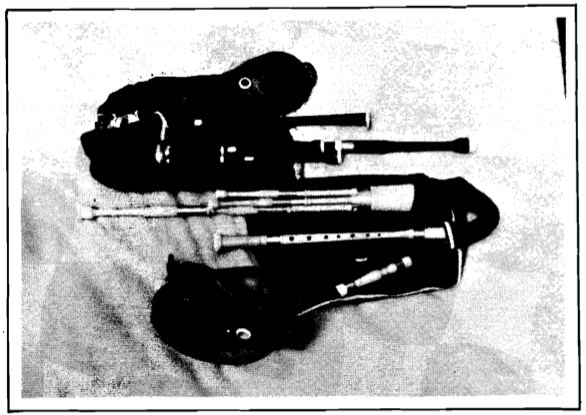

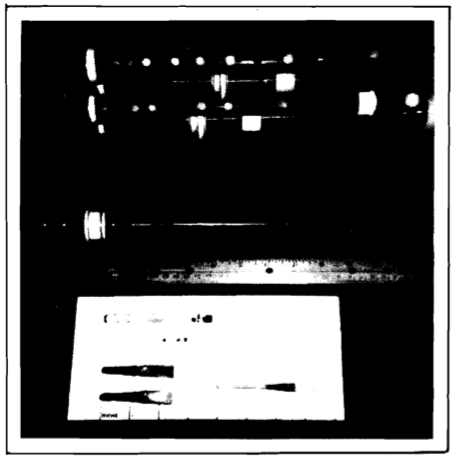

The following are the accounts and details of three historical bellows-blown pipes in my bagpipe collection. They are: a Scottish smallpipe; a Border pipe; and a Pastoral pipe. Photographs of the first two instruments appeared in the first issue of the Journal. All three are shown in the photographs below.

Scottish Smallpipe

I came by the set of Scottish smallpipes in 1989 through Denny Hall – pipemaker from Gig Harbor, Washington State – who kindly put the owner in touch with me. They were owned prior to my purchase by Michael Hubbert the great Hurdy Gurdy maker from California. When I purchased them they had an ebony chanter and drones, as shown. I believe the drones may be made of laburnum with old ivory and/or bone trim. No bellows came with the set, but they had a sheepskin bag with a tartan cover. The chanter obviously had come from a different source and period than the drones, which is supported by the different woods used and by stylistic differences. On a visit to Northumberland in 1989/1990 I took the set to Colin Ross who, as well as confirming these points, also made me a wonderful new chanter to match the drones. This is the chanter shown installed in the set in the photograph. Colin confirmed the following:

1. The drones are definitely Quite old, possibly late 18th, early 19th century.

2. The only set he has seen with a high fifth drone, i.e., the only Scottish smallpipe with this drone arrangement.

3. The combing on the drones is interesting – they have different designs and may come from different periods owing to repairs at different points in time.

4. The drone stock is combed.

5. The drones are powerful and have a rich sound, owing to relatively wide bore diameters. For this reason, they take a fair amount of air to blow.

6. The chanter with the set is an early goose chanter i.e., a Highland practice goose (not a practice chanter) which plays in C. The old goose chanter had been worked on extensively around some of the holes – maybe to try to get a B or Bb chanter to play in C to match the drone pitch. Colin pointed out that, while the chanter is very interesting, it is not one that necessarily will play well in light of all the modifications as the intonation of the instrument with the present reed is very poor.

Colin made the bellows shown in the photograph and fitted the drones with new reeds.

9

Border Pipes

How did I come by this set of Border pipes (top in photo)? The answer, in brief, started whilst playing Northumbrian smallpipes outside the beer tent at the Montreal Highland Games sometime around 1981/1982. A pipe band drummer approached me and told me of a set of bagpipes he had picked up in a pawn broker shop in Ontario, and that no one seemed to know much about them. He couldn’t get reeds, and none of his Highland piper friends could assist. His description of them immediately made me think — “gosh, could these possibly be an antique set of Border or Half-long pipes?” At this time the only such instruments I’d seen were the half-long sets played in the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society annual competitions in Newcastle. I should note that there was very little public activity with Lowland pipes in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s.

Anyway, he agreed to send them to me so that I could take a look at them. After a period during which I nearly forgot about seeing the set, they arrived in pieces in a box through the mail. It was an exciting moment to open the box and discover a truly antique set of Border pipes! The letter inside simply indicated that I should make an offer if I was interested…

David Quinn, the pipemaker, put a bag on the set and made me reeds. As the photograph shows, the set has two tenor drones and a bass drone. I well recall the excitement of first playing the set on the shores of Lake Champlain in autumn of that year. On a subsequent visit to Colin Ross I learned some interesting I things about the set:

1. The chanter is stamped in two places MacDonal(dl) Edin., which could date the pipes to the 1750 1820 period.

2. The drones are made of laburnum and the chanter is made of lignum.

Colin added a liner to the chanter bore to drop the pitch from near-B to Bb, allowing me to use a more standardized chanter reed. The chanter was very warped when I received the set, as it probably sat in a box for up to 100 years. Being lignum, the dry climate of North America subsequently produced the warpage. Despite this, however, it plays beautifully in tune. One thing I have proven with this chanter is that I can now play music around corners!

10

Pastoral Pipes

I came by the antique Pastoral pipes through Richard Butler, Piper to the Duke of Northumberland, who has been a featured teacher of the Northumbrian smallpipes at the North Hero Convention for several years now. They were owned by Bob Cowper, from near Newcastle. Bob was very involved with setting up the Cocks Collection and Bagpipe Museum in Newcastle. I purchased the set from him in 1987. As usual with Pastoral pipes, there is no makers name or other mark on them. Although the combing design is relatively simple, the set exhibits great craftsmanship. This is one of the few known old sets in circulation.

The set was complete (with bellows) except for missing a foot joint for the chanter and an end cap for the regulator. Colin Ross made replacement parts for these. Sam Grier has recently worked with myself on fixing up the set (we recently met at a hotel in Syracuse, New York for the purpose), and he has since done an excellent job producing a full set of reeds for them. I hope these stories are of interest to you and shed some insight into the enjoyment I have received from restoring and playing old instruments!

Alan Jones’ Pastoral pipe shown in two views: complete (top) and exploded (bottom).

Alan Jones’ Pastoral pipe shown in two views: complete (top) and exploded (bottom).

11

REEL, CHAMBER AND PASTORAL PIPES by Sam Grier

Well, what a very good thing. There is to be a second issue, number two I should think, of the North American Association of Lowland & Border Pipers Journal. There are Quite simply insufficient accolades to be directed towards the administration and staff of the Association. Despite the many impediments confronting such a “Labour Of Love” endeavour, here again another high Quality publication.

I should like to discuss the Reel and Chamber Pipes in this article. In order to properly address this it is necessary to also deal with the theory of tuning the Scots Small Pipes on a general basis. This will, or should, enlighten the reader regarding the fundamentals of the regulator, and how it is utilised, uniquely, within the two instruments. First off, the regulator’s function is Quite different from the Pastoral and Uilleanne Pipes. The sound emitted from the opened interval, or hole, is intended to be utilised as an accompanying drone sound. Also, the sounds can be played intermittently during the performance of the tune, to the taste of the performer. This is possible because the regulator is not keyed. Once exposed, the hole remains open until it is manually closed. In earlier days this was accomplished by the use of bees wax which simply plugged the hole closed. It was removed to expose the hole as desired. The piper kept the ball, or pellet, of beeswax in the crotch of his fingers to retain heat, making the pellet supple so it could Quickly and effectively block the hole as required. Personally, I use surgical tape for this.

The Chamber Pipe is named, not for a bed chamber as is generally believed, but rather for the air chamber within the drone stock which contains a “Scroll” that stops either drones or regulator sounds by directing the air as desired. Thus, both drones and regulator can be stopped and started at will during the performance. This instrument has three drones; A/B. d/e or D/E and a/b, one regulator; b,d,e,f,g, and a’. It is the same size as the Parlour Pipe, which is named after the parlour or sitting room. The Reel Pipe has two drones: A/B and a/b. Both regulators are b, d, e, f, g, & a’. Although two regulators set at thirds to each other on the same notes, are known also. This instrument is larger, the same size as the Border Pipe. Both chanters have nine notes but can, if reeded properly, be pinched and over-blown to achieve two or three higher notes.

Likely, you will have noticed that I Quoted two notes for each drone. This is true and possible for all Scots Small Pipes, provided they are properly made. I must say that I have seen only a few small pipe players who are aware of this feature. All small pipe drones should tune to the 1st and 2nd or 4th and 5th intervals respectively. Of course, in the event your pipe has more than three drones, the intervals will vary.

Right, now back to the Reel Pipe. The specific instrument to which I am referring ought not to be confused with the Lovat Reel Pipe, Quite another instrument. The Lovat Pipe is to put it quite simply, a mouth-blown Border Pipe. The Reel Pipe that I am discussing was frequently played by “Tinkers” and the like, and could have indeed been invented by them. Another name for the Reel Pipe is “Chanter Pipes”. I have been told that Tinkers frequently made Bagpipes from old discarded chanters of varying types. In other words the drones were chanters with all of the holes, except those wanted, blocked up. Now, it does not require much imagination to appreciate the musical possibilities of a bagpipe with three nine-noted chanters for drones. My understanding is that these Chanter Pipes were both mouth and bellows blown and were of varying sizes and almost unlimited tonal and acoustical properties. These pipes were very common indeed and only started to vanish during the religious reformations of the 17th and 18th centuries.

During the reformation, frivolity of any sort, particularly music was unfashionable. Bagpipes, which could apparently excite basic human emotions were considered as instruments of the devil. At revival meetings bonfires were built and fiddles, bagpipes, viols, harps, flutes, accordions, and witches were burned as an act of testimony to devotion. Of course there were some who could not bring themselves to burning or destroying their musical instruments. They either hid their instruments, or left town. The neighbors, of course, would not tolerate them. A man in Edinburgh was publicly flogged and stockaded because his canary whistled on the sabbath. A very great amount of Scottish music was lost forever because very few, Robert Burns was an exception, would write the music (staff notation) of songs. Instead, they wrote down, in poetry fashion, only the words, which also had been seriously “cleaned up”. So, the melodies of thousands of songs were totally lost.

12

Tinkers during this time found their ranks increasing as some musicians “hit the road”. Jamie MacPherson, the celebrated fiddler was one of these. After being arrested as a highway man he composed the tune “Jamie MacPherson’s Rant”. He played the tune at the gallows tree and, in contempt, offered his fiddle to any who would take it and play it, in spite of the church laws. When no one would, he smashed his fiddle against the heel stone and climbed the ladder. A man, at the hanging later wrote down the tune and so saved it. He said, years later, that the only reason he went to the hanging was to buy the fiddle from the hangman. When it was offered for free, he said he was afraid to take it. The fiddle was a famous one at the time, and there were others there also to barter for it, but because of the church presence, they also declined. Jamie MacPherson’s fiddle is now on display at the castle of the Chief of the MacPhersons, where ever that is. I read the story in a National Geographic article a few years ago. A very interesting story which I’m told is true.

Few people seem to be aware of the fact that the poet Robert Burns was a fair fiddle and cello player, and somewhat of an expert at staff notation. He single handedly saved an incredible volume of Scottish music which was nearly extinct even at his time. He also saved a great many tunes which were instrumental in nature by writing songs to the air. “Auld Lang Syne” is an excellent example. Burns originally set that song to the air of MacBeths’ Strathspey, a slightly different air, but much more elegant than the one we all sing at New Years. A most remarkable gentleman, Serge Hovey has devoted his life to Burns’ songs. Totally bed ridden on a breathing machine and only able to communicate by keyboard and computer, he has thus far restored 323 of Burns airs which would undoubtedly have been lost by matching the lyrics to the old music. The vocalist Jean Redpath is his elected communicator. Her seven taped record volumes are an excellent source of authentic 18th century lowland music for the piper looking for sources.

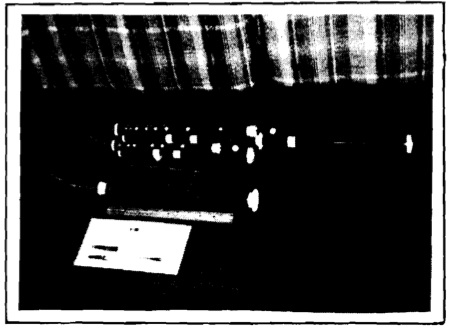

Now I’d like to talk in more detail about the Reel and Chamber Pipes. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, I enclose some pictures of my Reel Pipes and the reeds. In order that the reader may have a clearer understanding of the instrument, I have placed beeswax on the regulator holes in the traditional fashion. Thus you will be able to tell which intervals are used. Now, I tend to use rather more intervals than the traditional. They are as follows. On the B-flat or small regulator, b, d, e, g, and a’. On the A, or large regulator, G, b, d, e, f, g, a’ and b’. Both regulators may be sounded simultaneously, but only one elective note can sound on each regulator at the same time.

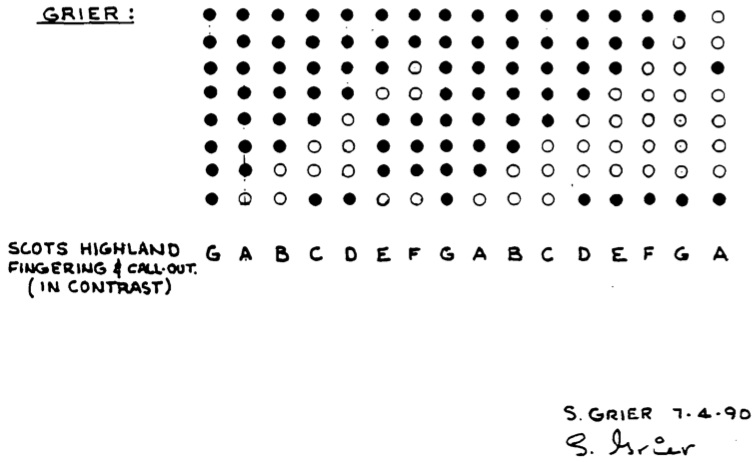

Figure 1. Overall view of the Reel Pipes and reeds, showing the two open regulators, with the beeswax in place.

13

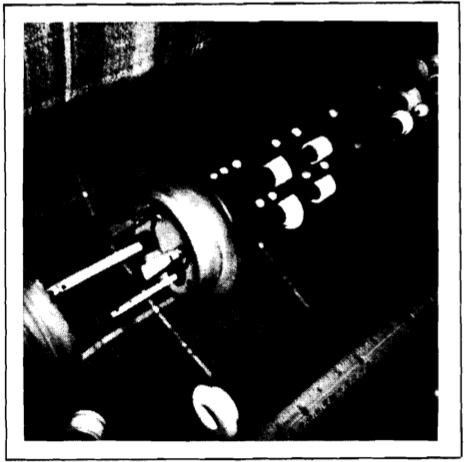

Figure 2. Detail of Reel Pipe: the drones, regulators, and reeds.

Figure 2. Detail of Reel Pipe: the drones, regulators, and reeds.

Thus, as you can see, the regulators are utilized as drones and are equipped with rushes for fine tuning. The two drones are in octaves to the fundamental, A, or B-flat. The chanter shown in playing position is pitched in B-flat and can double-tone a few notes above high a. In order to play a chanter in the key of A, the large regulator is interchanged with the B-flat chanter and now becomes the playing chanter. Thus, you now have two B-flat regulators in the key of A which then produces rather an eerie tonal quality in the minor keys. Generally only three drone sounds are used in small pipering but in the case of this uniquely versatile instrument, four drones can easily be used. The very high g, a, and b, regulator sounds are very effective and are much used for tunes such as “The Flowers of the Forest”, “Jock of Breadislee”, and the like. A combination of A’, A, d, and e is particularly effective, almost organ like, for George M. Cohans’ “Rosie O’Grady”, and Archie MacNeils’ “The Gairloch”, and other music hall type tunes.

The Chamber Pipe is very similar to the Reel Pipe excepting it has only one regulator of similar nature, and is smaller. I believe the photo of the reeds which is marked in inches, is self explanatory. You may note that the two regulator reeds are double-bridled while the chanter reed is single-bridled. The inside diameter of all three reed staples is 1/8″, the wall thickness is 1/64″. The chanter reed, interestingly enough, is also the correct reed for a modern Scots Pastoral Pipe. For older Pastoral Pipes, you likely can use a Uilleanne “D” reed but, you will need to reduce the diameter of the staple. This is very simply done by taking a plastic drinking straw and cutting it to fit inside the staple. Place the cut side of the straw at the left side of the flat of the blade and insert it in fully, all the way up to the beginning of the oval. Cut off any excess at the bottom of the staple. You will have accomplished two things here. One, you have reduced the internal volume of the staple thus, flattening the pitch from nearly E-flat to D, and you will have considerably mellowed the over all tone. It should play much more sweetly.

14

Figure 3. Detail of the Reel Pipe with its drone stock removed, showing the reeds in place.

I should also mention, as it seems a little unclear, that both the Reel and Chamber Pipes, when bellows blown, are commonly stocked. You may have observed that the main stock on the Reel Pipe in the photograph is quite large. This is because when I first made the instrument, it was to have been played by an actor playing the role of a piper in two Sean O’Casey plays in a theatrical production in Denver Colorado during, I think, 1971. I was quite concerned regarding moisture and so designed the stock over sized both in diameter, and in mass. This was so it would remain the coolest part of the instrument thus attracting entrained moisture to condense on its inner surface rather than on the reeds. I also put a chemical drying agent inside the pipe bag. As a matter of interest, it worked quite well. Later, I converted it to a bellows blown instrument but never did install a smaller stock as it worked just fine as it was. I’m a great believer in the old axiom “If it ain’t broke… don’t fix it!”. A lot of pipers would do well to remember that. I’ve seen more good pipes screwed up by being killed by excessive kindness than any thing else.

15

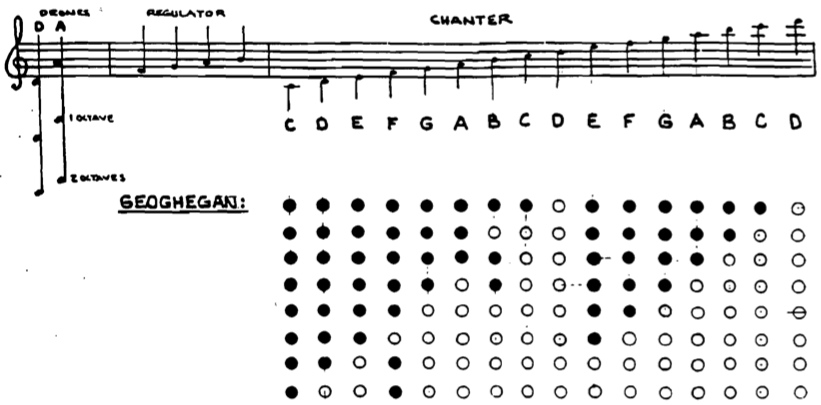

For those of you who are interested in fingerings, I have also included a finger chart comparison (next page) between the fingering of Geoghegan (1720) and myself with a call-out between Highland Pipe and Uilleanne and Pastoral Pipe note call-outs. You may note here that the note a Highland Piper would call “E”, is called by other Uilleanne, Pastoral, and tin whistle players the note”A”. That is the key to the difference in Highland Piping and other instrumental playing, they are apart by a fifth. In other words E = A, and A = E. Now, I am not saying here that one fingering system is better than the other. It will be found that if your background has been in Uilleanne piping or tin whistle, you will adapt more readily to Geoghegan fingering. If, on the other hand, your background has been in Highland, Scots Small, or Northumbrian piping you will find the Grier fingering more suitable. The choice is yours. You may want to utilize both patterns for different tunes or tempos.

Here is some very good news for anyone wanting to buy a set of Pastoral Pipes. I have recently been talking to John Addison, of Lincolnshire. He is the Master Pipe Maker who made my absolutely beautiful Pastoral Pipes. After a good deal of persuasion, John has decided that he will make Pastoral Pipes to order. Don’t miss out on this, there is no better maker! His address is listed in this issue under Bagpipe Makers.

Another master pipe maker who has revolutionized Scots Small Pipes is Robin Greensitt of Heriot and Allan. He has come out with, Quite recently, a set of Scots Small Pipes with a chanter range of, in Highland terms, Low E to High e, two full octaves. You can play anything with this instrument. The chanter has seven keys producing two notes below low G, and four notes above high A. I understand he has developed a fully chromatic chanter as well. There are six drones, all complex, which sound three notes each and are individually switched on or off at will. The range is in A/B flat and C/O. Each of the two sets comes with two interchangeable chanters. I have two sets of these pipes and they are superb, an absolute dream to play!

In the next issue, we will present a reprint of selected sections of Geoghegan’s tutor for the Pastoral Pipes, including the frontispiece and a few pages of music from the tutor. I believe it came out in circa 1720. and is the first known bag pipe tutor. Also there are many contemporary tunes in it like, “A Charming Nun To A Fryar Came”. Robert Burns would have loved that title. We should not lose sight of the fact that, while we may think this is ” OLD STUFF” at the time, it was new, refreshing, innovative, and Quite fashionably daring. For now, below is the piper illustrated in the frontispiece of the tutor. He is playing an instrument which looks like a reel pipe, having one open holed keyless regulator, one double bass, and one bass drone. Although Geoghegan doesn’t mention a regulator in the tutor, the second edition (Simpson’s edition) was some 20 to 30 years later and musical things were happening rapidly then. It was an exciting time and innovation was the rage all over Europe.

The tutor is 28 pages long and contains many tunes, contemporary to the circa 1720 period. Since any copyright restrictions regarding this very rare and valuable tutor have, no doubt, long since expired it can now be considered as public domain. I should be happy to provide a copy of the entire second edition to any who may wish to add this to their collection, at no cost. In the event you may feel it is worthwhile, you could send a donation to this publication as an expression of your personal support. I am indebted to Alan Jones of the North American Northumbrian Pipers Association, who very kindly sent me a copy. I do believe the original source of this publication was the American Society of Uilleanne Pipers, Tom Creegan president. So, our thanks is to them.

I see that, as usual, I’ve blathered on at some length again. So I’m going to wrap this little writing endeavor up now. I should like to close by saying that I do not consider myself to be any sort of an expert on bagpipes. Indeed if I have any expertise in any form, it is in the secure knowledge that I am no expert at all. I wish you all good luck, and good piping.

16

Figure 4. Pastoral Pipe Fingering and Tuning.

Figure 4. Pastoral Pipe Fingering and Tuning.

17

TOWN PIPERS – A EUROPEAN CONTINUITY by Brian McCandless

“…A baggepype weI coud he blowe and sowne,

And ther with al he brought us out of town. ”

Prologue to Canterbury Tales

Geoffrey Chaucer c. 1380

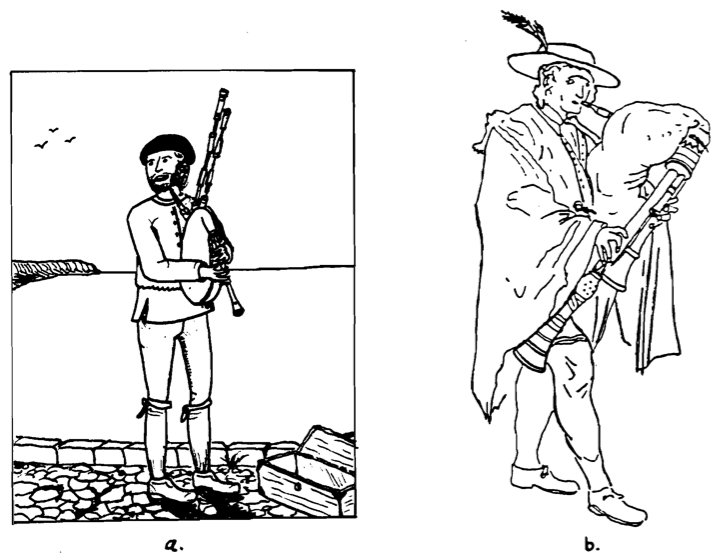

While Chaucer’s motive for mentioning the bagpipe skills of his Miller was merely to prove him a buffoon, he reveals a certain familiarity with the talented pipers of his day. Numerous references and allusions to bagpipers, in pastoral, religious, and urban settings, are to be found in the literature, poetry, visual art, and lore of 13th, 14th and 16th century Europe. To glance through the works of medieval and renaissance artists like Guyot Marchand (1490), Hieronymous Bosch (c.1490), Virdung (1511), Albrecht Durer (1514), Hans Holbein (1538), Pieter Brueghel (c.1550), Hans Sebald Beham (c.1550), Abraham Bloemaert (c.1600), Michael Praetorius (1619), and David Teniers (c.1650) is to witness a continuous documentation of pipers for every occasion. By way of example, we show the engraving by Mariette (c.1 650) of the shepherd playing his musette, a bellows pipe of the 17th century with an open chanter and shuttle drones.

Figure 1. Engraving by Mariette, after Michael Lasne, c.1650 entitled “Gallant Shepherd Playing the Musette”. The caption reads: “This shepherd, glory of his era, Stricken with a discreet flame, Gives his desire gaity, vigor, to his musette’s tender strain”.

18

Other examples are plentiful: there is mention in the priory records of Old Christ Church, Dublin, of Geoffrey the Piper in 1206; there is the Prussian tale of the piper of Hamelin who cleared a town of its vermin in Amoureux of 1375 in which the dancers call out for more drum, bells, cymbals, and bagpipes; there is a woodcut from “Le Calendrier des Bergers”, 1493, showing a piper bringing news of salvation to the shepherds; and there is Philip Stubbes puritanical account of Morris dancers in 1583, of the “heathen company [marching] towards the churchyard, their pipers pipying, their drummers thundering…with their hobbie horses, dragons, and other antiques…wherein they daunce all that day and all that night too. And thus these terrestrial furies spend the Sabbath-day.”! In everyday medieval life, then, we detect that pipers obviously played a noticeable if not important role.

In the German “Markt Platz” of the 14th to 17th centuries, the “Spielmann” was an important figure. variously acting as balladeer, musician, folk-dancer, animal trainer, and magician. Among his repertoire of musical instruments were the bauernleier (hurdy gurdy) and dudelsack, or German bagpipe, with its two drones emanating from a common stock. The spielmann was a mainstay of medieval Germanic society. a town fixture who was all at once a musician and gossip-monger.

The bagpiper fulfilled a ritualistic role in the southern provinces of Italy where he was literally the harbinger of the Christmas season. A few weeks before Christmas, the shepherds of Abruzzo, the Ligurian-Lombard Apennines. Istria, Lazio, Calabria, and Sicily would descend from the foothills and mountains and enter the towns with their flocks and their bagpipes (piva and zampogna) playing the tarentellas and Christmas novenas of the region. These medieval customs persisted until the time of the second world war.

Figure 2. Regional European pipers: a) Flemish doedelzak performer and b) Italian zampogna player of the Lazio province. Adapted from an engraving by J. Dumont (1739).

19

Pipers also played a more official role in the European courts and municipalities – they held a civil status which bonded them, albeit sometimes loosely, in service to a lord, court, or town. These “town pipers” were among European cities’ earliest civil servants, neither shepherd nor statesman, neither vagrant nor merchant, but poor civil servant.

One of the most notable literary references to a town piper occurs in Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, first published in 1722. Defoe’s book is a first person narrative and social commentary on the events which occurred in London in 1665, the year of the great plague. While he himself did not actually witness these events (he was born in 16601, many friends and family members did, and these provided the many anecdotes cited in the Journal. His occupation as a journalist led him to cover an outbreak of plague in Marseille in 1720, an event which no doubt initiated and provided further insights for his Journal. His tale about the town piper during the plague year is so relevant to our discussion that I have included the entire passage verbatim:

” … It was under this John Hayward’s care, and within his bounds, that the story of the piper, with which people have made themselves so merry, happened, and he assured me that it was true. It is said that it was a blind piper; but, as John told me, the fellow was not blind, but an ignorant, weak, poor man, and usually walked his rounds about ten o’clock at night and went piping along from door to door, and the people usually took him in at public-houses where they knew him, and would give him drink and victuals, and sometimes farthings; and he in return would pipe and sing and talk simply, which diverted the people; and thus he lived. It was but a very bad time for this diversion while things were as I have told, yet the poor fellow went about as usual, but was almost starved; and when anybody asked how he did he would answer, the dead cart had not taken him yet, but that they had promised to call for him next week.

It happened one night that this poor fellow, whether somebody had given him too much to drink or no John Hayward said he had not drink in his house, but that they had given him a little more victuals than usual at a public-house on Coleman Street – and the poor fellow, having not usually had a bellyful for perhaps not a good while, was laid all along upon the top of a bulk or stall, and fast asleep, at a door in the street near London Wall, towards Cripplegate; and that upon the same bulk or stall the people of some house, in the alley of which the house was a corner, hearing a bell which they always rang before the cart came, had laid a body really dead of the plague just by him, thinking, too, that this poor fellow had been a dead body, as the other was, and laid there by some of the neighbors.

Accordingly, when John Hayward with his bell and the cart came along, finding two dead bodies lie upon the stall, they took them up with the instrument they used and threw them into the cart, and all this while the piper slept soundly.

From hence they passed along and took in other dead bodies, till, as honest John Hayward told me, they almost buried him alive in the cart; yet all this while he slept soundly. At length the cart came to the place where the bodies were to be thrown into the ground, which, as I do remember, was at Mount Mill; and as the cart usually stopped some time before they were ready to shoot out the melancholy load they had in it, as soon as the cart stopped the fellow awaked and struggled a little to get his head out from among the dead bodies, when, raising himself up in the cart, he called out, ‘Hey! where am I?’ This frighted the fellow that attended about the work; but after some pause John Hayward, recovering himself, said, ‘Lord, bless us! There’s somebody in the cart not quite dead!’ So another called to him and said, ‘Who are you?’ The fellow answered, ‘1 am the poor piper. Where am I?’ ‘Where are you?’ says Hayward. ‘Why you are in the dead-cart, and we are going to bury you.’ ‘But I an’t though, am I?’ says the piper, which made them laugh a little though, as John said, they were heartily frighted at first; so they helped the poor fellow down, and he went about is business.

I know the story goes he set up his pipes in the cart and frighted the bearers and others so that they ran away; but John Hayward id not tell the story so, nor said anything of his piping at all; but that he was a poor piper, and that he was carried away as above I am fully satisfied of the truth of.”

20

Other documentary evidence of use of the town piper in Europe well into the 18th century surfaces in the documentation of J.S. Bach’s life. In his Lives of the Great Composers, Harold Schoenberg tells of the complaint Bach had while living in Leipzig, where his efforts to assemble an orchestra were confounded by the availability of mediocre musicians, among them “four town pipers, three professional fiddlers, and one apprentice…modesty forbids me to speak at all truthfully of their qualities and musical knowledge…”. The town piper’s duties ran the gamut from entertainer at official occasions, to town crier, to setter of military cadence and morale booster.

The alignment with the military was particularly close in England. Edward I leaned heavily on his pipers for at least four different military engagements: the Gascony campaign of 1286-1289, the Flanders campaign of 1297, and the Scottish campaigns of 1298-1300 and 1303-1304. In 1307, under Edward II, court records show two payments made to a piper named Janino Chevretter. Pipes were requisitioned for use at the Battle of Inverlochy in 1431. In 1475, a regiment of pipers accompanied Edward IV to Calais, and through the 16th century, pipers saw duty at such battles as Tournay, Belgium (1513), the siege of Boulogne (1544), the battle of Yellow Ford (1598), and the battle of Curlew Mountain (1599). The list goes on…culminating with the formation of Highland pipe regiments in the early 17th century. The dedication of the regimental pipers to their duty was never so apparent in historical memory as that exhibited during World War I, in which many pipers lost their lives in their roles as pipers under fire, stretcher bearers, and soldiers.

In England and throughout much of Europe, as the 16th century waned, evidence of pipers in general faded from the documentary evidence. It is curious, though, that their presence in everyday life persisted in relatively isolated areas such as central France and in the so-called “Celtic Fringe” areas: Brittany, Galitia, Asturia, Sardinia, Scotland, and Ireland. In England, one of the last images of a public piper is William Hogarth’s 1733 woodcut of Southwark Fair, in London.

Figure 3. Detail of “Southwark Fair” by William Hogarth.

21

In the Border counties and in Northumberland, however, the piper continued to fill a civil position through the 18th century, and in Northumberland, the post of “Piper to the Duke of Northumberland” has been filled up to the present day. The principal task of the town piper in the Lowlands and Northumberland was to signal the morning and evening hours by piping along a specified route or at a given location. Their more familiar counterparts were the town criers of 19th century London. The Northumbrian towns of Alnwick, Hexham, Morpeth, Newcastle, Roxburgh, and others had town pipers, known as Corporation pipers or “waits”, whose lives and service have variously been documented. The Newcastle waits. in the course of their evening rounds, stopped to play beside a special chalk mark thus scribed on the side of a building:

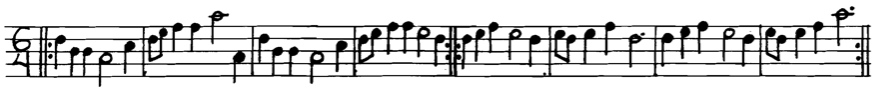

The first edition of John Playford’s Dancing Master (1651) lists a tune titled, simply, “The Waits”

(setting adapted for Lowland pipes) Much has been written concerning the “Toun Pipers” of the Borders, but for all this documentation I have yet to see an explanation of how the pipers, with their reputation for late night indulgences, were capable of rising in the morning before their laird, burgess, mayor, or duke to play Reveille! Maybe they owned a dog, kept chickens, …

In William Stenhouse’s notes to Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum we find an interesting reference to some notable border pipers:

“…The late Mr. Alexander Campbell, editor of Albyn’s Anthology, made occasional tours to different parts of the country, partly with the object of collecting local tunes; and I possess a manuscript journal by him, in 1816, when he visited Roxburghshire, in which he has introduced a notice of the most eminent Border pipers of the last century, which I may take this opportunity to extract. As stated, it was written down from the communication of Mr. Thomas Scott at Monklaw (the uncle of Sir Walter ScottI who was himself a skilful performer [of the Border pipes].

” Monday, 21 st, Mr. Thomas Scott performed many pieces on the pipe, two of which I noted down; after which, I jotted down the particulars following regarding the best Bag-pipers of the Border, most of whom he himself knew personally.

” A list of the best Border bagpipers (together with a few particulars regarding them) who lived from about the beginning of the year 1700, down till about the commencement of the year1800, noted down from Mr. Walter Scott’s uncle, Mr. Thomas Scott, presently resident at Monklaw, near Jedburgh…:

“1. Walter Forsyth, piper to Mr. Kerr of Littledean, Roxburghshire: He was an excellent performer.

” 2. Walter Forsyth (son of the former) was gamekeeper to the then Duke of Roxburghe; the son was reckoned likewise a good piper.

” 3. Thomas Anderson, by trade a skinner, in Kelso. The father and grandfather of Thomas Anderson were esteemed good performers on what is called the Border or Bellows-bagpipe.They lived about the close of the seventeenth century.

22

“4. Donald Maclean, piper at Galashiels (father to the well-known William Maclean, dancing master in Edinburgh), was a capital piper, and was the only one who could play on the pipe the old popular tune of “Sour Plums of Galashiels,” it requiring a peculiar art of pinching the back hole of the chanter with the thumb, in order to produce the higher notes of the melody in question. He died about the middle of the eighteenth century. Richard lees, manufacturer in Galashiels, has the said William Maclean’s bagpipes in his possession.

” 5. John Hastie, piper of Jedburgh, lived about the year 1720 (see his elegy). He was the first performer who introduced those tunes now played in Teviotdale on the bagpipe. Mr. Thomas Scott is decidedly of opinion, that the Border bellows-bagpipe is of the Highland (or, at any rate, the north-east coast) origin, as all the pipes with whom he was acquainted positively declared. This is a remarkable fact, not generally known, and difficult of belief. The small Northumberland bagpipe differs considerably from the one alluded to, particularly in the mode of execution. The successor of John Hastie, was

” 6. Robert Hastie (nephew of the former). Mr. Thomas Scott, thinks that Hastie succeeded his uncle about the year 1731: he was reckoned a good performer.

” 7. George Syme was supposed to have been born and bred in one of the Lothians. He was the best piper of his time; he knew the art of producing the high octave by pinching the back hole of the chanter, which was reckoned a great improvement. He was the best piper of his day. He lived about the middle of the eighteenth century.

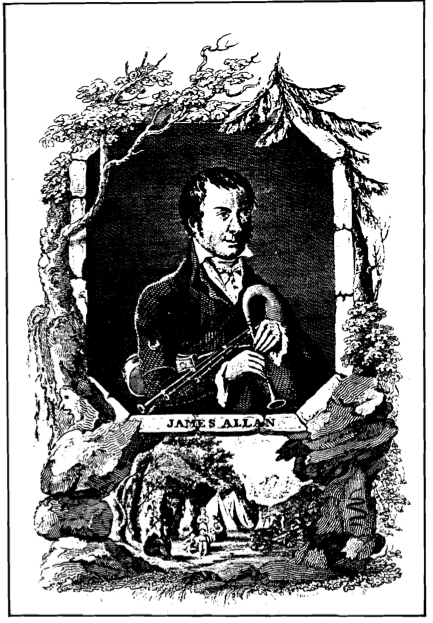

” The earliest Pipers (Mr. Thomas Scott says) of the Scottish Border, properly speaking, were of the name and family of Allen, who were born and bred at Yettam, in Roxburghshire. They were all tinkers. The late James Allen was piper to the Duke of Northumberland, and was the best performer on the loud and small bagpipes of his time. He being a Border-lifter, the poor fellow was caught hold of in some of his lifting exploits, and cast into prison; but escaping justice, and set at large, he renewed his bye-jobs, was again incarcerated, and condemned to be hanged; which sentence was, at the solicitation of the Duchess of Northumberland, changed to imprisonment for life. He died in jail, at the advanced age of eighty years and upwards, about two months before his pardon came down from the King; this happened in the year 1808.”

” After jotting down the preceding notices respecting the most celebrated Pipers of the Border, I took my leave of the venerable, cheerful, intelligent, and worthy gentleman who so liberally made the communication, and proceeded to Jedburgh, which is within little more than a mile from Monktoun, to deliver my letter of introduction to Robert Shortreed, Esq., the Sheriff substitute of Roxburghshire, the old and intimate friend of his brother sheriff, Water Scott.”

“Sir Walter Scott records, that his uncle, Mr. Scott, “died at Monklaw, near Jedburgh, at two of the clock, 27th January 1823, in the 90th year of his life, and fully possessed of all his faculties. He read till nearly the year before his death; and being a great musician on the Scotch pipes, had, when on his death-bed, a favourite tune played over to him by his son James, that he might be sure he left him in full possession of it. After hearing it, he hummed it over himself, and corrected it in several of the notes. The air was that called Sour Plums in Galashiels.”

(Lockhart’s Life of Scott, vol.i. p. 102. 12mo edit.)

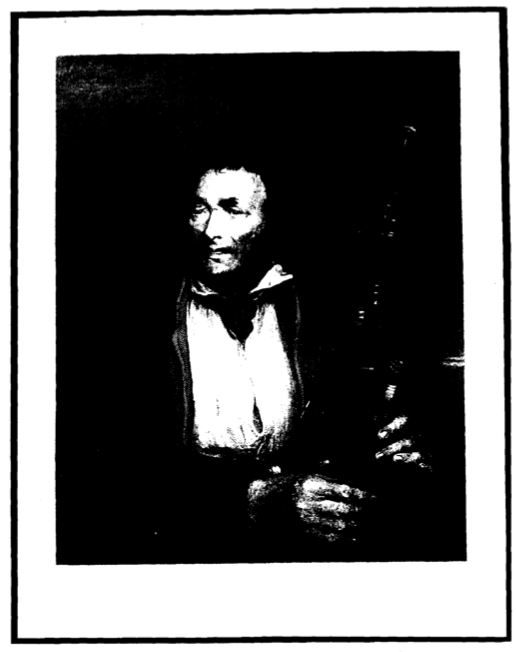

Mr. Stenhouse additionally writes, “It may be added that, in Kay’s Portraits, vol.ii. p.137, there is a biographical sketch and portrait of George Syme, one of these pipers. He was an inhabitant of Dalkeith, and died probably about 1790. The print is dated 1789, and bears the following inscription

This represents old Geordy Sime,

A famous piper in his time.

23

Figure 3. Portrait of George Syme, from Kay’s Edinburgh portraits, c. 1835. The now famous portrait caption reads: “This represents old Geordie Sime, a famous piper in his time”.

24

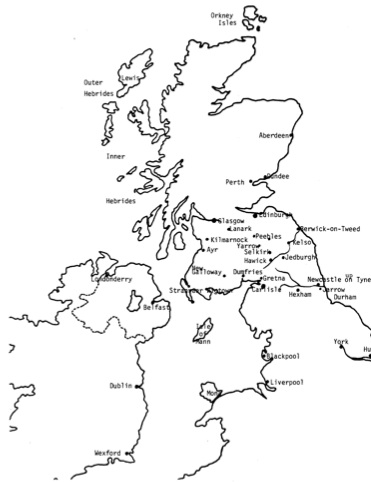

The following is a list of selected town pipers about whom some documentary evidence is available regarding their lives and times. Many other “laichlaund” towns, such as Perth and Selkirk, are known to have paid pipers for walking the rounds as well, so this list is nowhere near complete. Consult with the map on the inside front cover of this issue for the locations of the towns.

- Town of Haddington

- James Livingston Town Piper from ? – 1783

- Town of Hawick

- Thomas Beattie Town Piper from 1694 – 17?

- James Olifer Town Piper from 1717 – 1720

- Robert Foulier Town Piper from 1721 – 1732

- John Meader Town Piper from 1732 – 1741

- Walter Bellingden Town Piper from 1752 – 1756

- William Brown Town Piper from 1756 – 1757

- Walter Bellingden Town Piper from 1757 – 1778 last Piper

- Town of Jedburgh

- Hastie or Hasty Family of pipers, since 1500

- John Hastie Town Piper c.1513

- John Hastie Town Piper from c.1720 – 1731

- Robert Hastie Town Piper from 1731 to ? last Piper

- Town of Kilbarchan

- Halbert Simpson Town Piper from c.1600

- Town of Dalkeith

- George Syme Town Piper from c.1750

- Jamie Reid Town Piper

- Town of Galashiels

- Donald Maclean Town Piper? died c.1750

- Town of PeeblesPiper Ritchie Town Piper? – 1807

25

Figure 4. Portrait of James Allan (c.1734-1810) Piper to the Duke of Northumberland in the late 18th century.

That the town pipers as a Border institution eventually faded away is not surprising, especially as towns grew in size and diversity. What is surprising, though, is that their heyday lasted close to 300 years! The beginning of this heyday coincided with their occurrence in other parts of Europe. Whatever their critics may have said along the way, these pipers generally enjoyed the support of their townfolk-at-Iarge. This sentiment has never been more eloquently expressed than in the Epitaph to John Hastie, the town piper of Jedburgh at the time of the Battle of Flodden:

“Here lies dear John, whase pipe and drone,

And fiddle aft made us glad;

Whase cheerfu’ face our feasts did grace

A sweet and merry lad.”

26

THE BAG IN BAGPIPES by Michael MacHarg

Over the centuries, bagpipe bags have been made of many different and varied materials, some of them very successfully adapted, some not so. What have we learned about the basic qualities of a successful pipe bag?

1. It must be completely airtight.

2. It must have a sufficient volume to supply the necessary air to the chanter and drones.

3. It should be comfortable to hold under the arm and should be firm but not stiff.

Two broad categories of materials are presently used to make bagpipe bags: natural leathers and synthetics. Leather may be produced from cowhide, sheepskin, goatskin, and many other natural hides. Synthetics include plastic, rubber, and coated fabrics such as Gore-Tex. Until recently, the material used depended very much on the resources available to the pipe maker. For example: bagpipes of eastern Europe (Bohemian, Bosnian, Estonian, Hungarian, etc) traditionally have used sheep, goat, or kid skin bags – with the fur left intact on the outside of the instrument; bagpipes of Galitia, Spain (Gaida) have used rubber bags; and bagpipes of Scotland traditionally used sheep or goat skin bags.

Leather seems to satisfy the qualities necessary for pipe bags and has been successfully employed for centuries. When tanned in a certain way, the leather is very airtight, produces a firm feel, and is aesthetically pleasing to look at. Leather tanned in this manner has two sides -a very smooth “buff” side and a rougher “flesh” side (suede). In the United Kingdom, many bags are sewn with the buff side out, which causes problems with obtaining an airtight seal. Though these bags are made from well-tanned leather, they must be further treated with “bag seasoning” to be rendered airtight. As I see it, there are two disadvantages associated with this bag design:

1) With the flesh side of the leather on the inside of the bag, the rough surface must soak up a lot of seasoning to make an airtight seal. After the seasoning has been applied, what you have is an oil soaked bag. In time, the oil in the seasoning penetrates the bag, reaching the outer surface, making it slick and messy. This is not a situation I would care to have my instrument in.

2) When the finished, or buffed side is on the outside, the bag is slippery anyway and is therefore difficult to hold under the arm. Even with use of a bag cover (which mops up oil as weill, the bag itself slips around inside. Thus I favor bags sewn with the flesh side out, as they require only a thin internal coating of bag seasoning. If any oil does penetrate, it is kept from contacting the player by the rough texture of the outside of the bag. Additionally, the bag does not slide around under the player’s arm.

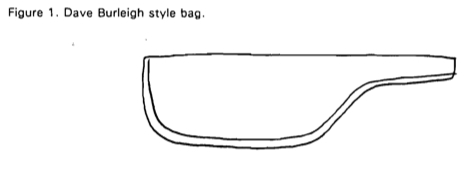

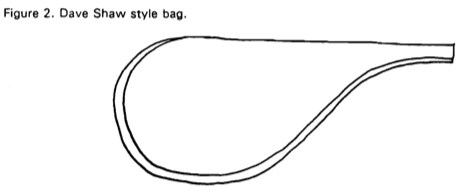

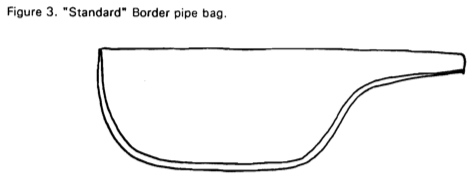

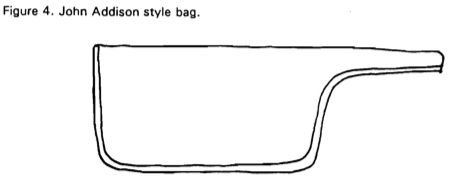

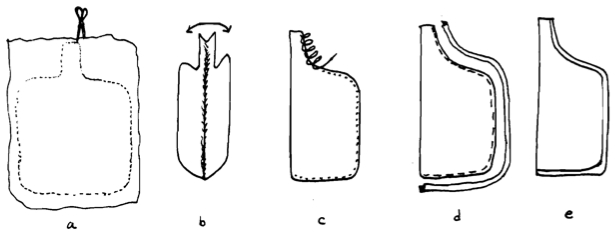

The size and shape of the pipe bag has a great influence on the player’s comfort and on the optimal performance of the instrument. There must be a balance between the size needed to do the job (keep the reeds going steadily) and the physical fit to the player. Below find sketches of some of the more popular shapes and sizes of bags used on Lowland and smallpipes today.

27

28

Bagpipe bags can be constructed in a variety of ways. In the case of those eastern European pipe bags, sometimes the entire hide is used and the stocks are simply tied into the leg and head appendages! For the Lowland or smallpipe bags, however, the bag is constructed from a piece of leather which is cut, folded, and attached around the edge as shown below.

Figure 5. Generalized pipe bag assembly

Figure 5. Generalized pipe bag assembly

Different methods are employed to fasten the seam of the bag: hand sewing, machine sewing, riveting, and gluing. These are described below.

Hand sewing – probably the oldest form of construction for bags that do not use the entire animal. It is one of the securest methods used today and is very pleasing to the eye.

Machine sewing -a newer method which guarantees longevity to the hands of the maker! This method produces good airtight bags.

Riveting -a very new method of bag construction. To many people, it is not as aesthetically pleasing, but with a bag cover, the point is a moot one. The method is easy, and, surprisingly, it does noticeably increase the weight of the bag.

Gluing – another new method of construction. With the wrong adhesive, however, the bag may fly apart. Otherwise, it makes a very attractive and streamlined bag and has been employed by many makers with varying degrees of success.

For those who would cover their bag, it is largely a matter of personal preference. It can dress up a set of pipes very nicely! One is limited only by the imagination, for every type, texture, and color of fabric is available, with a full contingent of lacework, fringing, and other adornments. Popular combinations are printed fabric; velvet and fringe; baize and lacework; and even burlap has been spotted.

To conclude, I would like to say that I make bags of all styles and sizes, including those shown above. I make bags by either hand sewing, riveting, or gluing, depending on the customer’s preference. If anyone in the membership has a Question concerning pipe bags, I encourage them to contact me!

29

29A

WHAT JOCKEY SAID TO JENNY

AND OTHER LYRICAL ILLUMINATIONS OF LOWLAND SCOTS MUSIC

by Brian McCandless

“Jocky said to Jeany, Jeany, wilt thou do’t?

Ne’er a fit, quo’ Jeany, for my Tocher-good;

For my Tocher-good, I winna marry thee.

E’ens ye like, quo Jonny, ye may let it be.

“I ha’ Gowd and Gear, I ha’ Land eneugh,

I ha’ seven good Owsen ganging in a Pleugh;

Ganging in a Pleugh, and linglink o’er the Lee,

And gin ye winna take me, I can let ye be.

“I ha’ a good Ha’ House, a Barn, and a Byer

A Stack afore the Door, I’ll make a rantin Fire;

I’ll make a rantin Fire, and merry shall we be;

And gin ye winna take me, I can let ye be.

“Jeany said to Jocky, gin ye winna tell,

Ye shall be the Lad, I’ll be the Lass my sell:

Ye’re a bonny Lad, and I’m a Lassie free,

Ye’re welcomer to take me, than to let me be. “

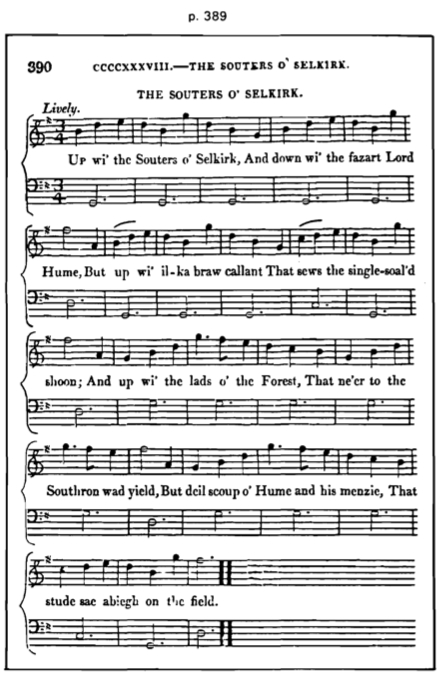

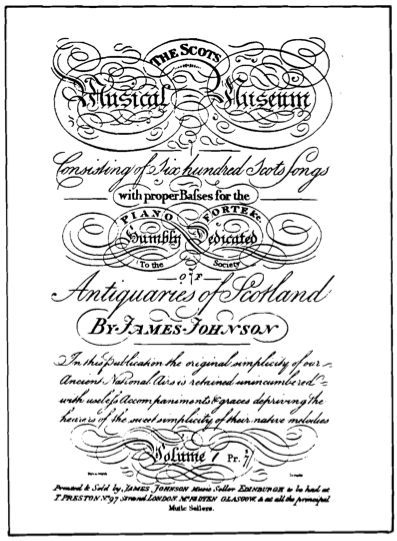

This poem, taken from the 1733 Edition of William Thomson’s Orpheus Caledonius. is an early variation on the Jockey-Jenny-Johnny theme prevalent in Scots song of the 18th century. During this period, a considerable quantity of collecting, composing, and re-writing Scots lyrics occurred (remember Robert Burns?). so that many lyrical variations now exist for a given song. In some cases, such as the tune “O’er the Hills and Far Away”, the tune is considered to be of 17th century origin, and at that time was believed to be an “old pipe tune”, although several poems now exist bearing the name. William Stenhouse, in his notes to the songs presented in James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum (1853 Edition, first published by Johnson in six volumes, from 1787 to 1803), alludes repeatedly to “old pipe tunes” used for Scots songs.

In this article I pursue this theme a little. that is, presenting the stories behind some of the Scots tunes that have come down to us as songs which we now put to the chanter. Of special interest are those which are referred to as pipe or dance tunes by Mr. Stenhouse. Being North Americans. we often find ourselves singing Scots songs and playing the pipes with only a meager grasp of the context and history behind the musical traditions. This is not our fault, for many of us are far removed from original sources of historical information of this kind. Although I am not an historian, I have found great pleasure in rummaging the library’s shelves for historical documents relating to bagpipe music. I must credit much of my motivation in these endeavors to the travails of Gordon Mooney and to discussions with Richard Butler, Hamish Moore, Pete Coe. and John Kirkpatrick.

Without inciting a riot over which came first, old songs or old pipe tunes, we could argue that the songs found in the old collections consist of 17th and 18th century poetry applied to older melodies, which mayor may not have been used for much older songs. Credence to the view that the tunes once had lyrics is lent by the following observation of Margaret Fay Shaw from South Uist on Hebridean song (1940):

“I never heard my friends in Glendale hum or sing an old tune without words. To them the words and air were inseparable. I once mentioned that I thought a neighbor had the air of a song, and the reply was, ‘how could she have the air and not the words?’.”

30

What follows then is a selection of lyrics and background information concerning some of the Lowland tunes, taken directly from the 1853 edition of the Scots Musical Museum. Where space allows, exact quotes are given. Otherwise, the notes have been paraphrased. The selections given here were somewhat randomly selected, based on my own prejudices, but are intended to represent some of the more well-known Lowland pipe tunes. Versions of the tunes may be found in Gordon Mooney’s tutor and tune collections (see Reference section).

Favorite Tunes of the Border Musicians

These two tunes are mentioned as being among the favorite tunes of the Border musicians and were notably recalled by Mr. Stenhouse as being oft’ heard in his youth. Both are undoubtedly very early Border pipe tunes. To the lover of Border music and to the pipe player, these tunes survive as the musical embodiment of the Border spirit, harping back to the end of the medieval era in northern Britain.

Johnie Armstrong: another old tune, this one commemorates the aggressive apprehension and execution in 1529 of Johnie Armestrang of Gilnockie and his gang of thieves (forty-eight in all) by James V, who had gone to Borders to restore law and order. The tune first appeared in print in Oswald’s Caledonian Pocket Companion around 1740 and provides the melody for several Scots songs.

Souters of Selkirk: an ancient Border tune dating to the time of the Battle of Flodden-field (1513) between James IV, King of the Scots, and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey. The title refers to a regiment of “souters” or shoemakers who gave their lives in the first wave of battle. To this day their fall is commemorated in the song, “Flowers of the Forest” (are a’ wede awa’). At the end of the day, the only man to return was William Bryden, who led the eighty or so Souters 0′ Selkirk – he returned carrying the captured banner of Edmond Howard. Today his banner is carried aloft at the “Riding of the Marches” whilst the tune “Souters O’Selkirk”is played. Stenhouse, however, presents us with some commentary by Dr. Samuel Johnson and Mr. Joseph Ritson, who disputed the origins of this ballad. A few lines of Mr. Ritson’s Historical Essay taken from Stenhouse’s notes suffice to make the point:

” For all this fine story there is probably no foundation whatever. That the souters of Selkirk should, in 1513, amount to fourscore fighting men, is a circumstance utterly incredible. It is scarcely to be supposed, that all the shoemakers in Scotland could have produced such an army, at a period when shoes must have been less worn than they are at present…Away then with the fable of The Souters of Selkirk!”

In the lengthy discourse which follows, Mr. Stenhouse appeals to the Scottish sensibitity of his readers, adding:

” … These erudite and very ingenious authors have not scrupled to affirm, that the natives of North Britain are more prone to believe in absurd and extravagant traditions than any other nation whatever; that the Scots had no shoes until Cromwell’s soldiers taught the people to make them; and that all of Scotland could scarcely have mustered an army of eighty shoemakers at the battle of Flodden.”

p. 384

Four pages later, he wraps up his excellent documentary evidence supporting the so-called “fable of Selkirk”:

” … John Brydon, a citizen of Selkirk, his lineal descendant, is still alive, and in possession of the sword of his brave ancestor. A standard, the appearance of which bespeaks its antiquity, is still carried annually, on the day of riding their common [ground], by the corporation of weavers, by a member of which it was taken from the English in the field of Flodden. This the Editor has often seen. Thus every

circumstance of the traditional story is corroborated by direct evidence.

31

“That the ballad, a corrupted fragment of which is inserted in the Museum, relates to the eventful battle of Flodden, the Editor, who was born and educated in the neighborhood of Selkirk, has not the smallest doubt…The words, as well as the genuine simple air of the ballad, both of which have been shockingly mutilated and corrupted, are here restored,as the Editor heard them sung and played, by the border musicians, in his younger days. The original melody is a bag-pipe tune, of eight diatonic intervals in its compass; a bass part has therefore been added, in imitation of the drone of that

instrument…

p. 389

32

Concerning the 3/2 Hornpipe

These old tunes – Wee Totum Fogg – The Dusty Miller – Go to Berwick, Johnnie – Mount Your Baggage – Robin Shure in Har’st – Jockey Said to Jenny, etc, have been played in Scotland, time out of mind, as a particular species of ‘the double hornpipe’. The late James Allan, piper to the Duke of Northumberland, assured the present Editor, that this peculiar measure originated in the borders of England and Scotland. Playford has inserted several of them in his Dancing Master, first published in 1658. Some modern imitations of this old style appear in Gow’s Repositories, and several other collections of Scotch tunes.”

p.456

The first stanza of the old ditty to the 3/2 hornpipe, “Wee Totum Fogg”, which was also used for a song called “Wee Willie Gray”, goes like this:

Wee Totum Fogg

Sat upon a creepie;

Half an ell 0 ‘gray

Wad be his coat and breekie.

Another 3/2 hornpipe was used as the melody to “a foolish song” called “Go to Berwick, Johnny” (#518) which began:

Go, go, go,

Go to Berwick, Johnny;

Thou shalt have the horse,

And I shall have the poney,

In the days of mischief and thieving along the Scottish-English border (known as reiving), safety for a fugitive could be found by crossing the river Tweed into Berwick. The poem given in the Museum has Johnnie driving the English back the other way, thus:

Go to Berwick Johnny,

Bring her frae the border;

Yon sweet bonnie lassie,

Let her gae nae farder.

English louns will twine ye,

0′ the lovely treasure;

But we’11 let them ken a sword,

Wi’ them we’ll measure.!

Go to Berwick,Johnny,

An’ regain your honour;

Drive them o’er the Tweed,

An’ shaw our Scottish banner.

I am Rab the King,

An’ ye are Jock my brither;

But before we lose her,

We’ll a’ there the gither.

33

A glance through Playford’s Dancing Master reveals a considerable number of 3/2 hornpipes and a larger number of 6/4 hornpipes, called ‘jigs’ in the collection. The tonal range on many of the tunes is nearly two octaves, making it unlikely that they were pipe tunes. A list of tunes which may be performed on the Lowland pipe with slight melodic modification, however, follows:

The English Passepied

The Seige of Limerick

Old Abigail’s Delight

News From Tripoli

A Morisco

Sion House

Cavylilly Man

The Tiger

The Hare’s Maggot

A Passepied

Mr. Isaac’s Maggot

Lady Banbury’s Hornpipe

Two of Nathanial Gow’s 3/2 compositions found in his Repository are “Miss Baird of Saughtonhall” and “Miss Mary Lumsdane’s Favorite”. A version of the 3/2 hornpipe, “Go to Berwick, Johnie”, is also found there.

The Reel of Stumpie (#457)

” This fine lively old reel tune wanted words, and [Robert) Burns supplied the two stanzas, beginning “Wap and row the feetie o’t,” inserted in the Museum. The tune may be found in the Collections of Aird, Gow, and many others. The Reel of Stumpie was formerly called “Jocky has Gotten a Wife,” and was selected by Mr. Charles Coffey for one of his songs, beginning “And now I am once more set free,” in the opera “The Female Parson, or Beau in the Suds,” acted at London 1730.”

p. 403

Wap and rowe, wap and row,

Wap and row the feetie 0 ‘t,

I thought I was a maiden fair,

Till I heard the greetie 0 ‘t.

My daddie was a Fiddler fine,

My minnie she made mantie 0;

And I myself a thumpin Quine,

And danc’d the reel 0′ stumpie O.

A similar meter is used in the song, “The Mill, Mill 0”, in which “they danced the miller’s reel 0”. The melody to this old song first appeared in Walsh’s Caledonian Country Dances (1734) as “Butter’d Pease” by which name it is still known in Northumberland. An obvious reference to the male organ, the song has been associated with Lowland weddings. In this context, we see the tune adapted for the Highland pipes as the “Highland Wedding”.

34

Mary Scott, The Flower of Yarrow (#73)

” This ancient border~air originally consisted of one simple strain. The second, which, from its skipping from octave to octave, is very ill adapted for singing, appears to have been added about the same year, 1709, and was printed in Thomson’s Orpheus Caledonius, in 1725, adapted to the song written by Ramsay, beginning “Happy’s the love that meets return,” consisting of three stanzas of eight lines each, which is very far from being in his best style. I have frequently heard the old song, in my younger days, sung on the banks of the Tweed. It consisted of several stanzas of four lines each; and the constant burden of which was, “Mary Scott’s the flow’r 0′ Yarrow.”

” This celebrated fair one was the daughter of Philip Scott of Dryhope, in the county of Selkirk. The old tower of Dryhope, where Mary Scott was born, was situated near the lower extremity of Mary’s lake, where its ruins are still visible, She was married to Walter Scott, the laird of Harden, who was as renowned for his depredations as his wife was for her beauty. By their marriage-contract, Dryhope agrees to keep his daughter for sometime after the marriage, in return for which, Harden binds himself to give Dryhope the profits of the first Michaelmas moon. One of her descendants, Miss Mary Lilias Scott of Harden, equally celebrated for her beauty and accomplishments, is the Mary alluded to in Crawfurd’s beautiful song of “Tweedside.”

” Sir Walter Scott says, that the romantic appellation of the “Flower of Yarrow,” was in latter days, with equal justice, conferred on the Miss Mary Lilias Scott of Crawfurd’s ballad. It may be so, but it must have been confined to a very small circle indeed, for though born in her neighborhood, I never once heard of such a circumstance, nor can I see any justice whatever in’transferring the appellation of the “Flower of Yarrow” to her descendant, who was born on the banks of the Tweed.

” The old air of the Flower of Yarrow, as has been said, consisted originally of one strain, to which a second had been annexed, not earliest than the beginning of the last century. The same subject was afterwards formed into a reel for dancing tune, to which my late esteemed friend, Hector McNeil, Esq. wrote a very pretty song, beginning “Dinna think, bonnie lassie, I’m gaun to leave you.” But, in the first number of Mr. Gow’s Repository, which was published a few years ago, this tune is called “Carrick’s Rant,” a strathspey; and the compiler of this Collection asserts, that “the old Scotch song (he must certainly mean the air) of Mary Scott, is taken from this tune.” The converse of this supposition is the fact; for Carrick’s Rant is nothing else that Clurie’s Reel, printed in Angus Cummings Collection. But the tune of Mary Scott was known at least a century before either Clurie’s Reel, or Carrick’s Rant, were even heard of.”

p.77-78

Tweedside (#36)

” In the Muses Delight, printed at Liverpool in 1754, this beautiful old Scottish melody is erroneously attributed to Signor David Rizzio, a musician in the service of Mary, Queen of Scots. The real name of the composer is unknown. Prior to the birth of [Allan] Ramsay, in 1684, it was adapted to the following verses, which are said to have been written by Lord Yester.

When Maggie and I were aQuaint,

I carried my nuddle fu’ hie;

Nae lint-white on all the gay plain,

Nor gowdspink sae bonny as she.

I whistled, I pip ‘d, and I sang,

I woo’d, but I came nae great speed,

Therefore I maun wander abroad,

And lay my banes far frae the Tweed. “

p. 36

35

O’er the Hills and Far Away (#62)