To download the original journal as a scanned pdf please click here.

OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF

LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 3 AUGUST 1991

CONTENTS

QUOTATIONS ………………………………………………………………………….2

FROM THE EDITOR……………………………………………………………..3

COMMENTARY…………………………………………………………………………………..4

LETTERS……………………………………………………………………………………….6

GEOGHEGAN’S TUTOR……………………………………………………………9

LINCOLNSHIRE BAGPIPES………………………………………………….21

AN EARLY SET OF UNION PIPES……………………………………30

A PLETHORA OF PASTORAL PIPES…………………………..32

PIPES, MAYPOLES AND THE MORRIS DANCE – by Brian McCandless…………34

REED-MAKING – by Steve Bliven and Mike MacHarg…………44

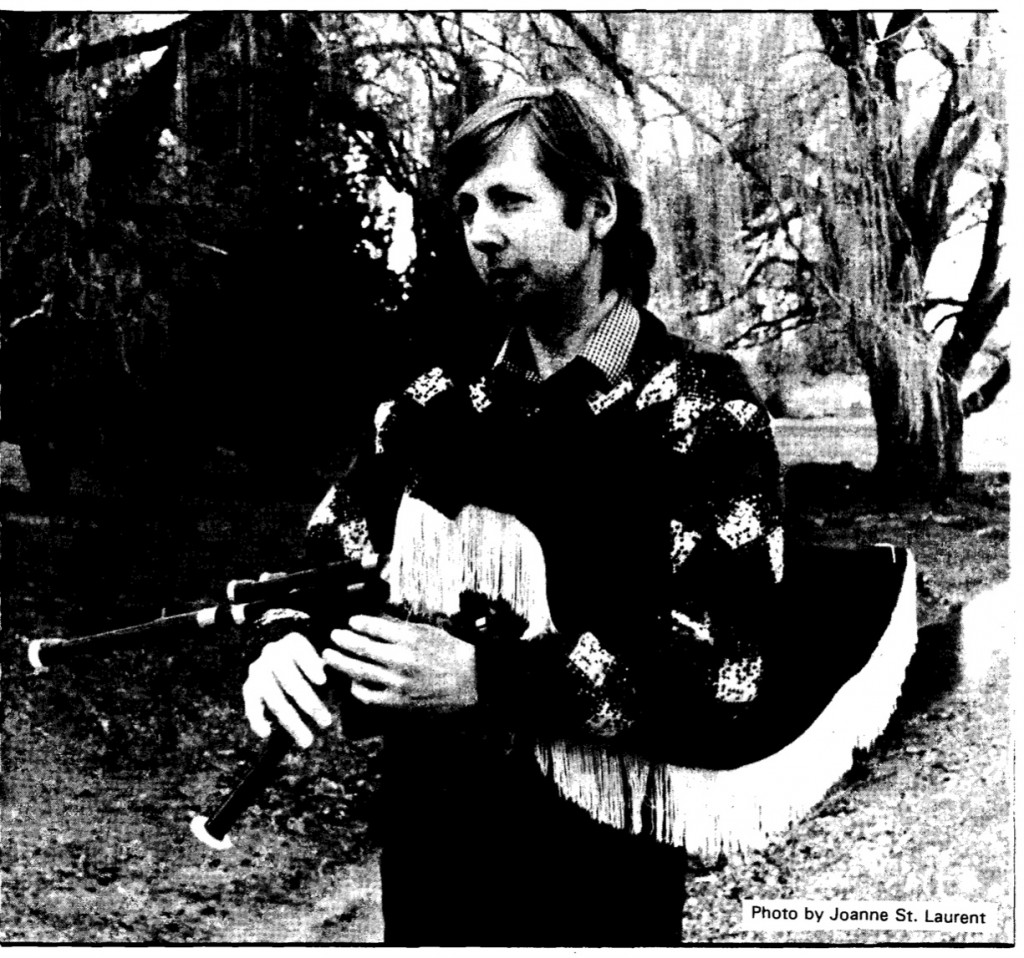

PROFILE – Alan Jones……………………………………………………………………53

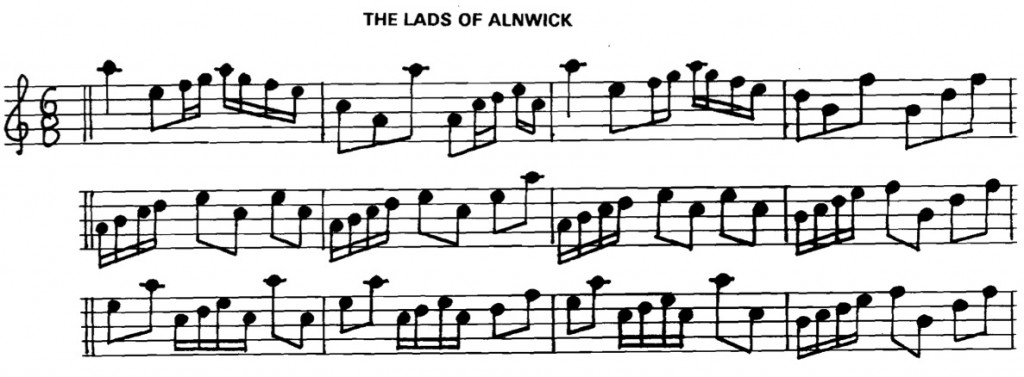

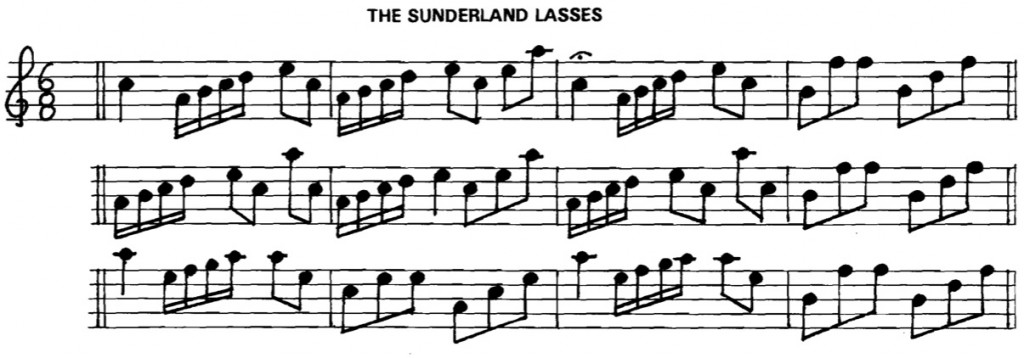

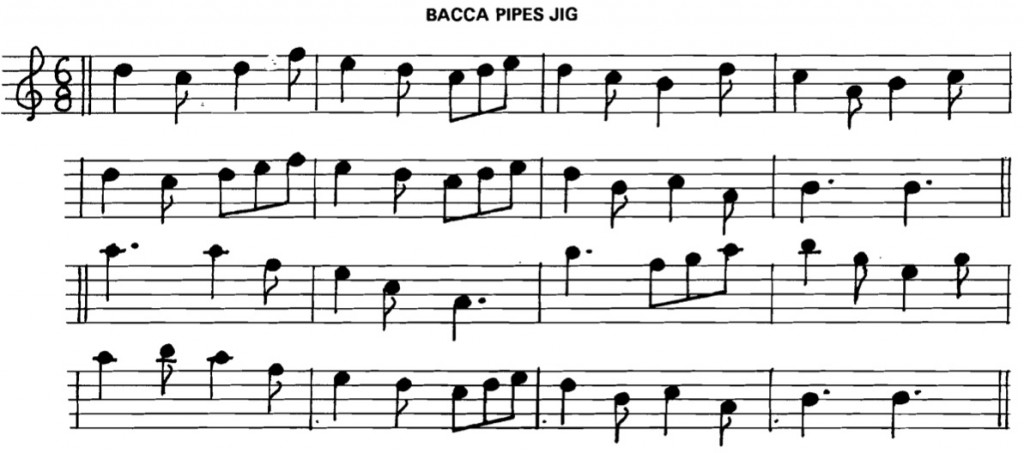

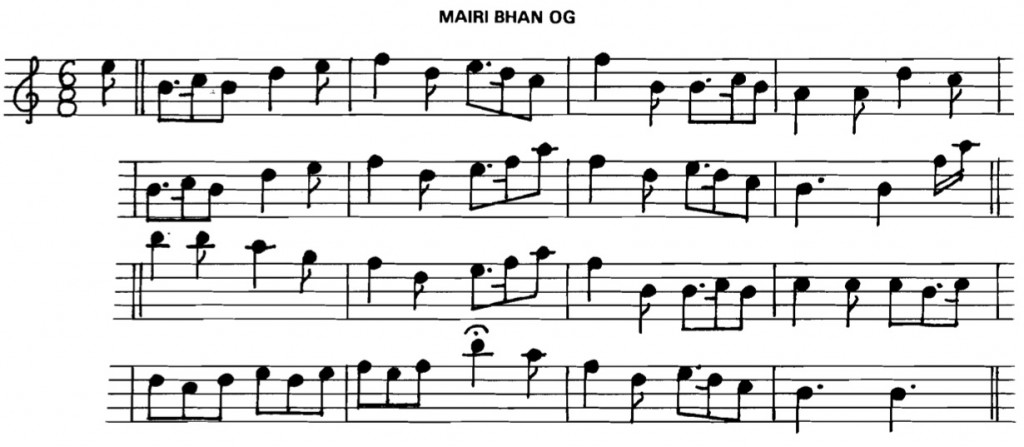

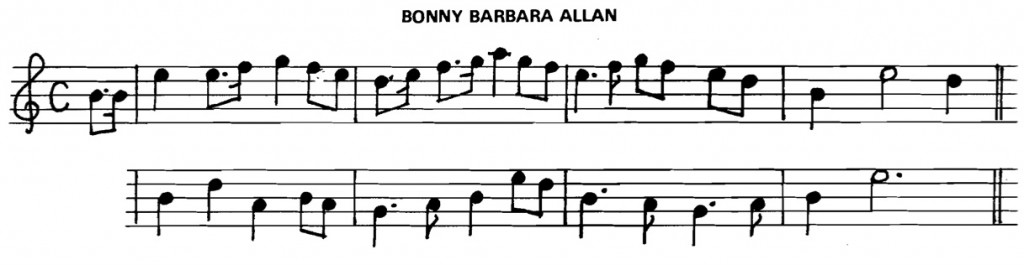

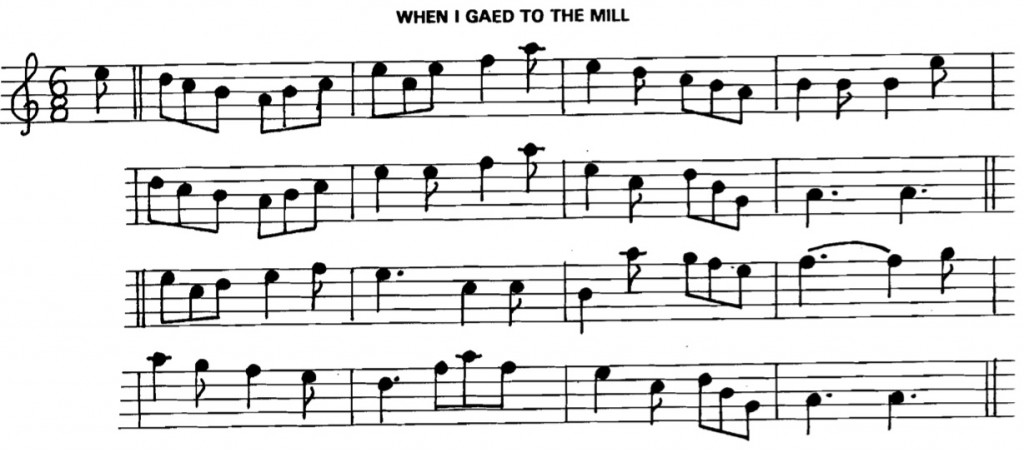

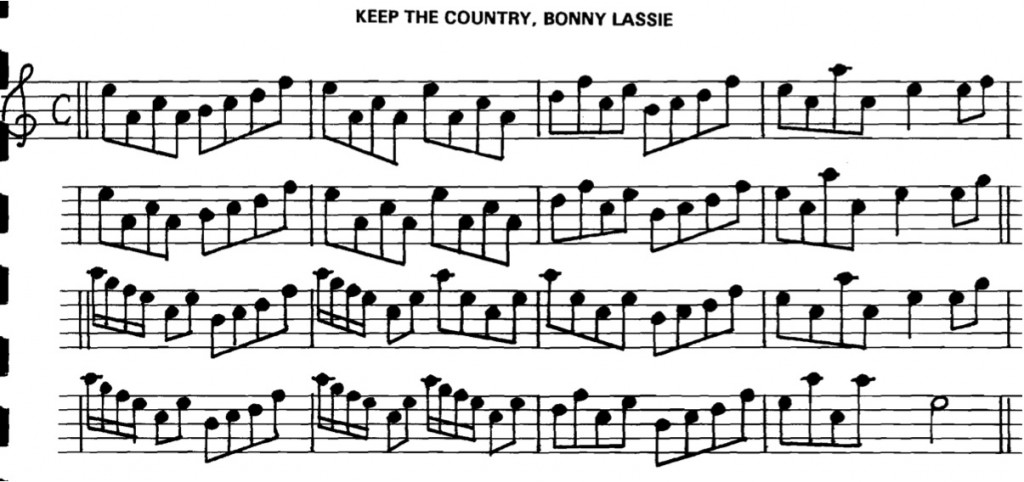

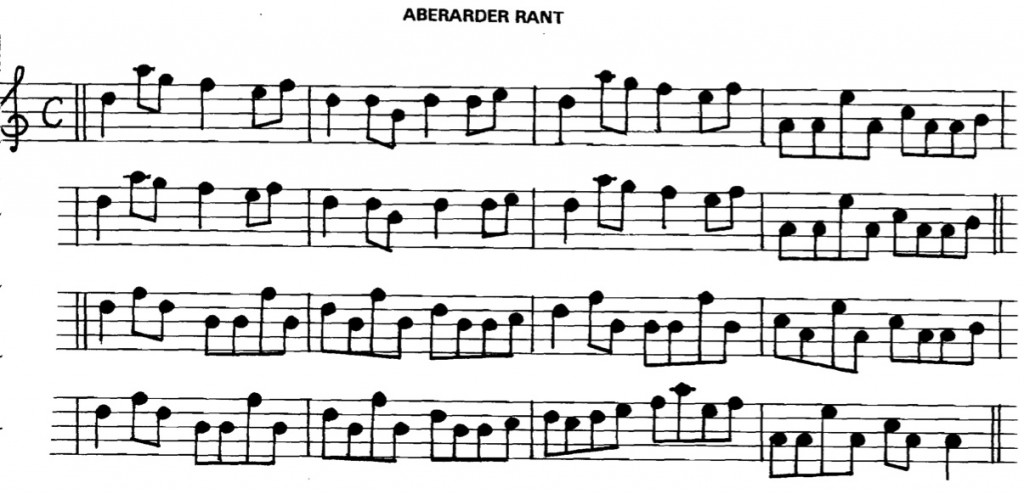

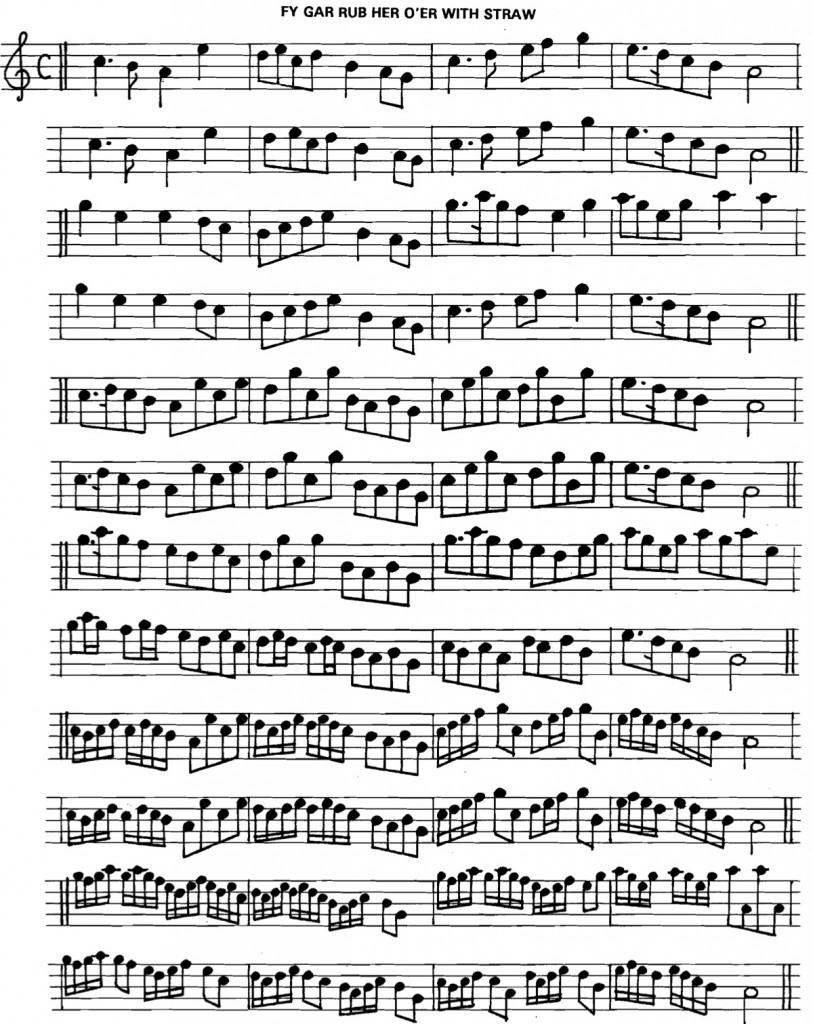

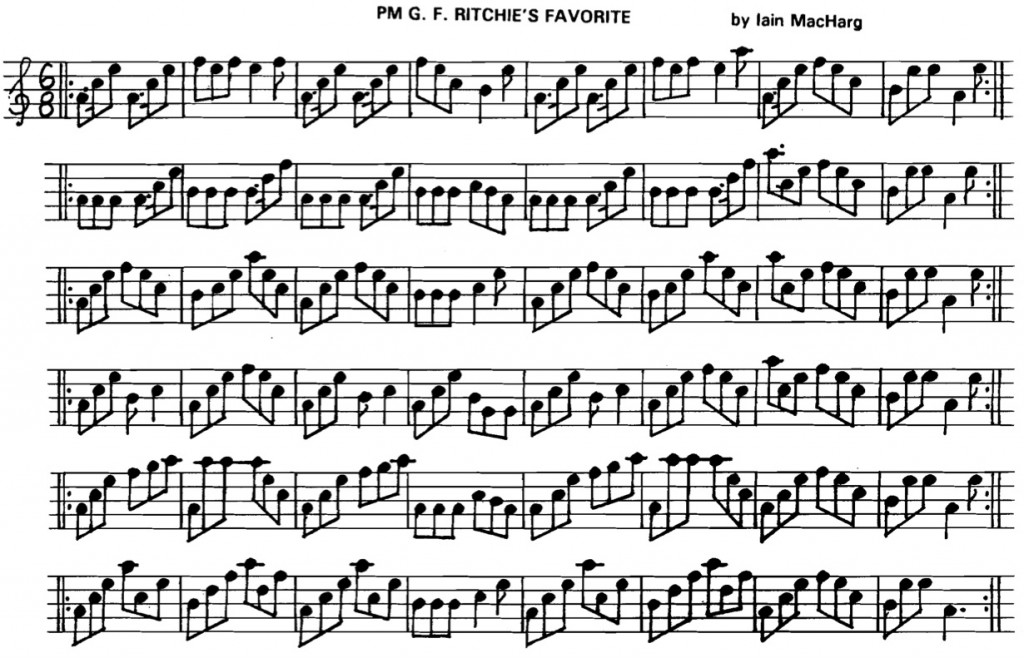

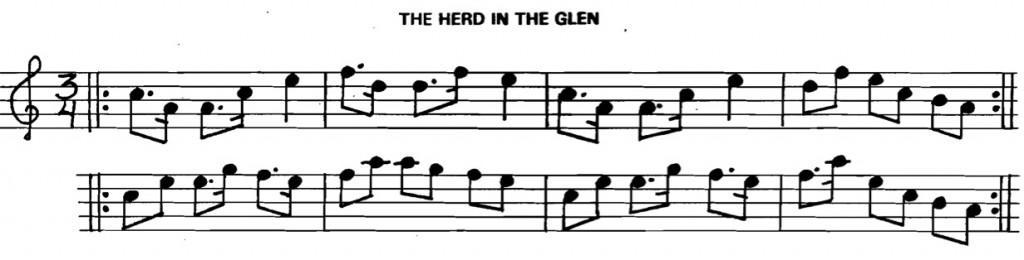

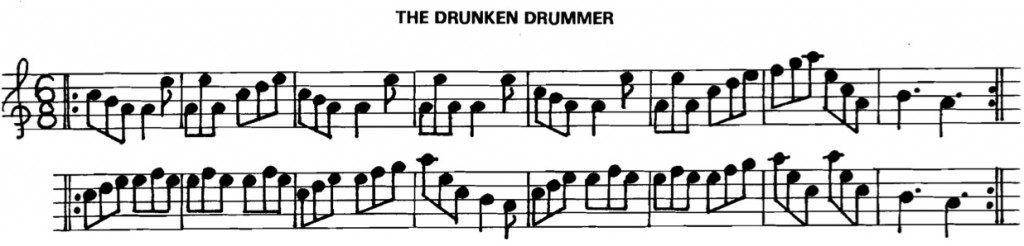

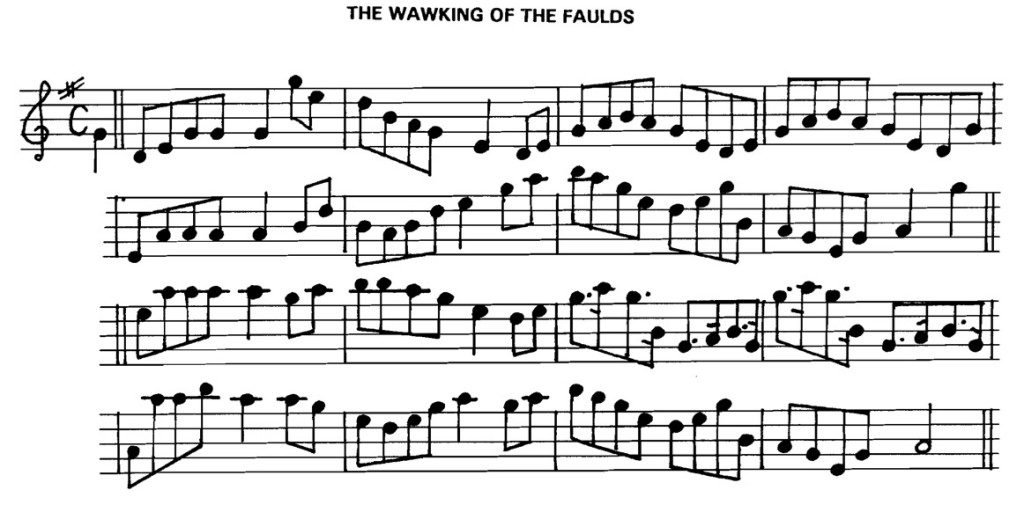

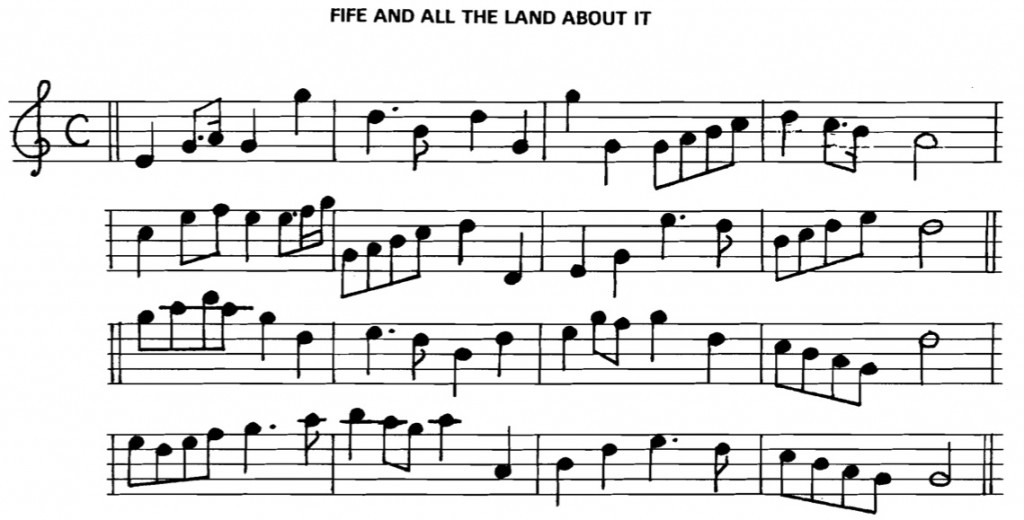

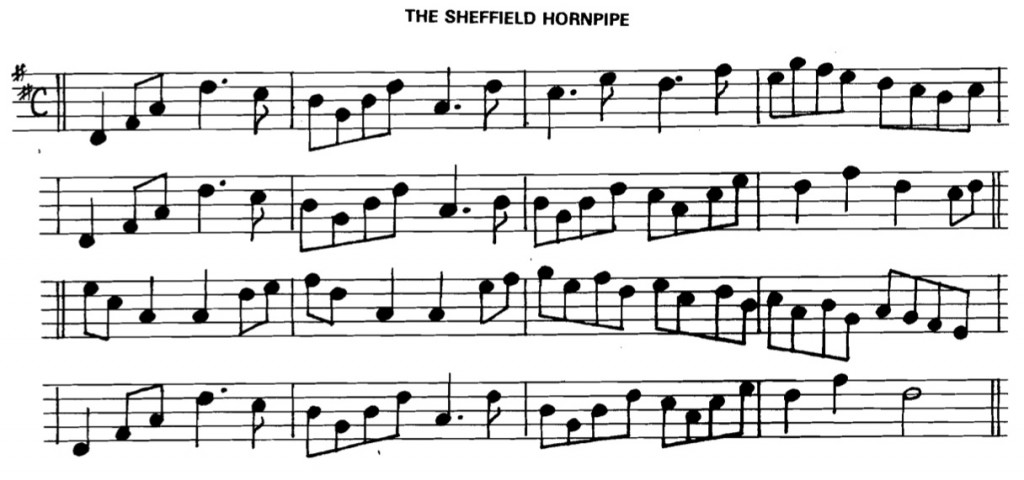

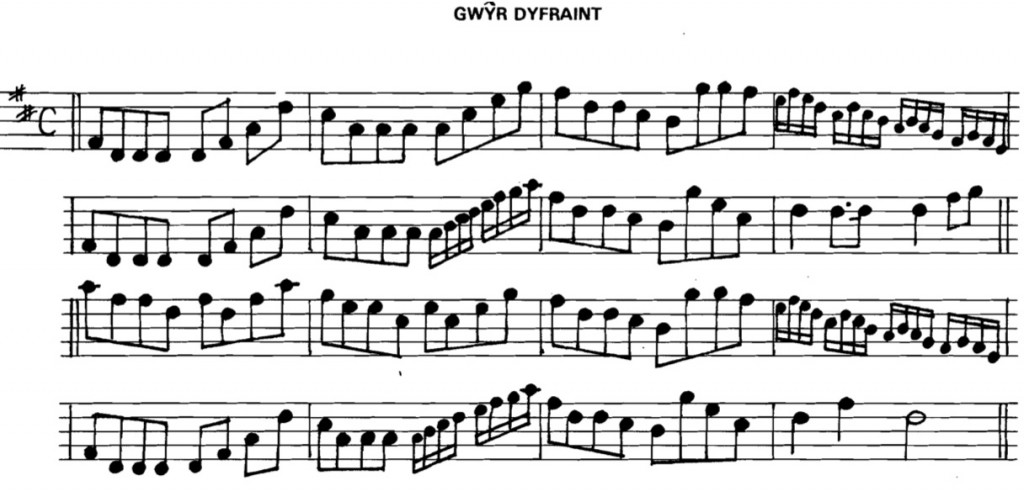

TUNES FOR LOWLAND PIPES, SMALLPIPES, AND PASTORAL PIPES 5

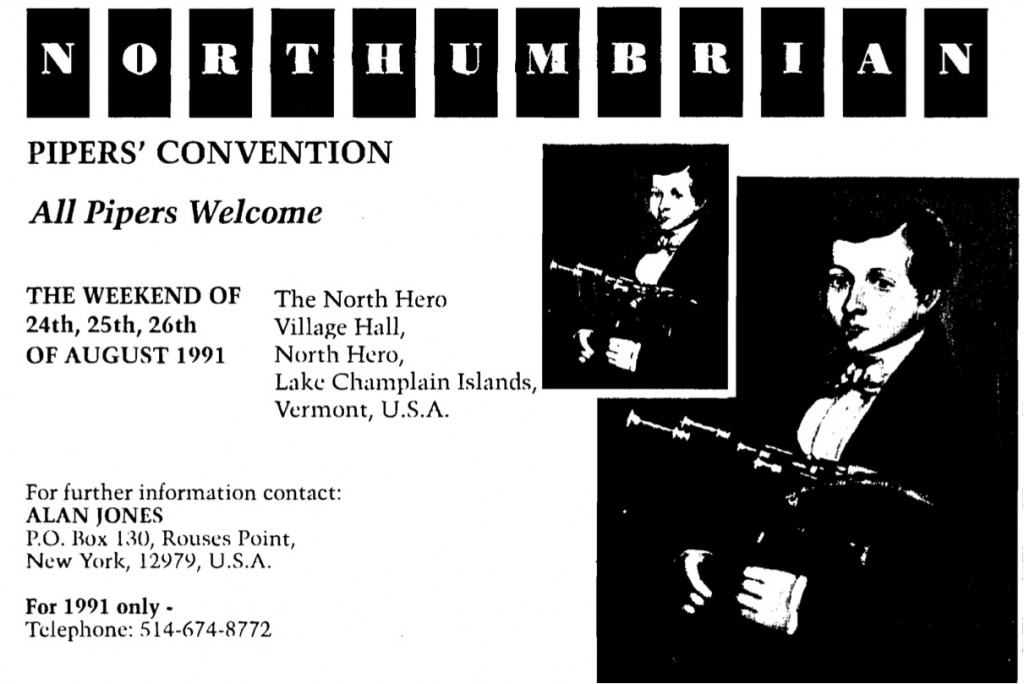

NORTH HERO CONVENTION…………………………………….67

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS………………………….68

N.A.A.L.B.P. MEMBERS LIST……………………………………………..69

MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION

1

————————-

—————————-

QUOTATION PAGE

“Caus michtilie the warlie nottes breike

On Heilands pipes, Scottes, and Hybernicke.”

[Cause mightily the warlike notes break

On Highland pipes, Scots (Lowland pipes), and Irish (pipes)]

Alexander Hume

(1598)

The following snippet appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 16, 1991:

"...Communism is like bagpipes, only even worse. A mother once asked Sir Thomas Beecham,the British conductor, what instrument -violin? trombone? - her son should take up. She said she was worried about the possible wear and tear on family nerves from her son's first efforts. Sir Thomas recommended bagpipes: they sound exactly the same when you have mastered them as when you first begin learning them."

Miscellany:

"There are no good reeds. We just learn to play the bad ones."

-Tim Britton

"Moses was certainly a piper, for he was found among the reeds."

– Anonomyous

"A wedding without a bagpipe is like a funeral."

– Bulgarian Saying

"It is better to play a simple tune well than a difficult one poorly."

-?

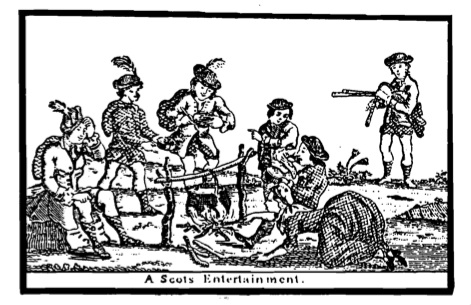

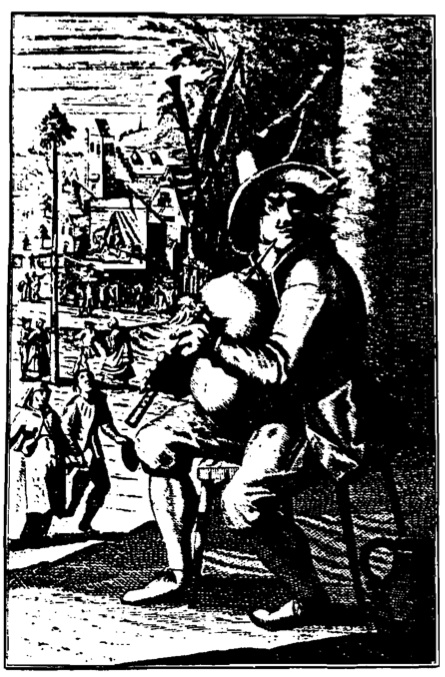

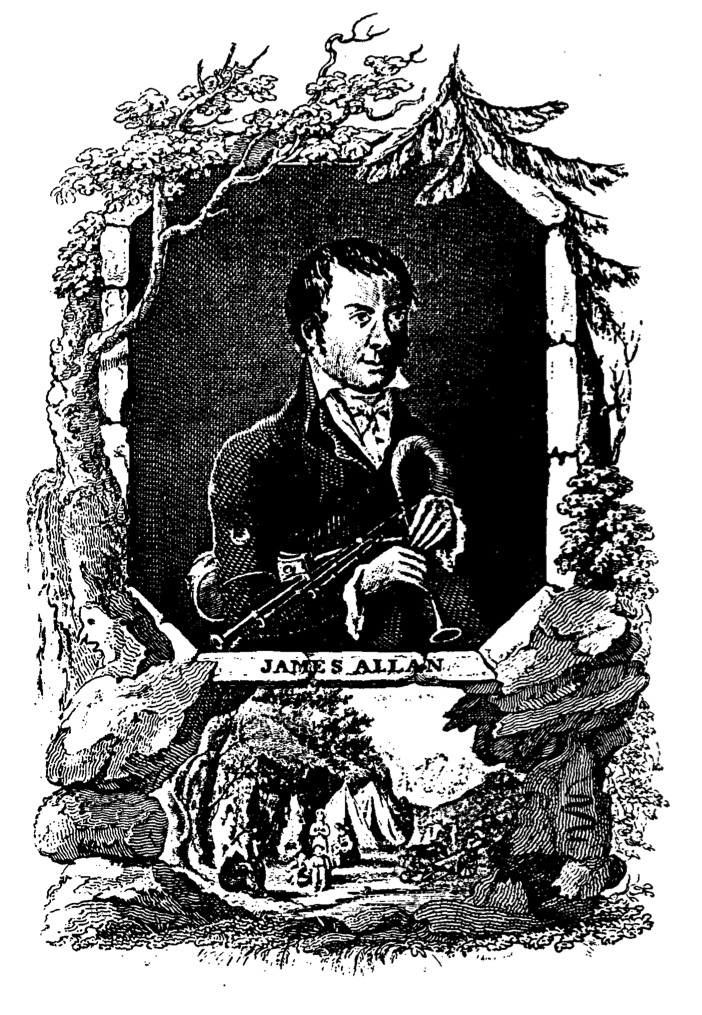

“Catchpenny Print” of “A Scots Entertainment” published c. 1780 by Bowles and Carver, London. Notice the garb and the long chanter! Sent in by W. Richmond Johnston, Accord, New York.

“Catchpenny Print” of “A Scots Entertainment” published c. 1780 by Bowles and Carver, London. Notice the garb and the long chanter! Sent in by W. Richmond Johnston, Accord, New York.

2

——————

FROM THE EDITOR

We are pleased to bring you Journal Number 3 of the North American Association of Lowland and Border Pipers! This issue represents a slight, but hopefully intriguing departure from the previous two issues. In the tune section we have included more melodies from the English and Welsh dance repertoire, a recently composed jig, and more tunes for the Pastoral pipes. We have several articles in reprint, one from John Addison on the Lincolnshire bagpipes, a short note from Denny Hall on early Union pipes, and (as promised in Issue #2) selected pages from Geoghegan’s Tutor for the Pastoral or New Bagpipe (c.1746). I have also prepared an article which, in addition to historical aspects of pipes, anticipates their use in diverse contexts such as Maypole, Morris, and Welsh dancing – ethnic activities which now enjoy a broad base in North America.

Since the last issue, I found an additional reference to Lowland town pipers, in Grattan Flood’s, The Story of the Bagpipe, (1911), page 67, which I’d like to share: “With reference to the burgh or town pipers, whose office was, as a general rule, hereditary, Mr. Glen writes as follows: – ‘About springtime and harvest the town pipers were wont to make a tour through their respective districts. Their music and tales paid their entertainments, and they were usually gratified with a donation of seed corn. They received a livery and a small salary from the burgh; and, in some towns, were allotted a small piece of land, which was called the piper’s croft. The office, through some unaccountable decadence of taste, was gradually abolished”

Mr. Flood adds a footnote of historical interest, namely that one Fergus Neilson was appointed “toune pyper” of the burgh of Kircudbright for one year, starting December 2, 1601. Flood then indicates that towards the end of the 17th century, the Highland clans also adopted a policy of retaining pipers.

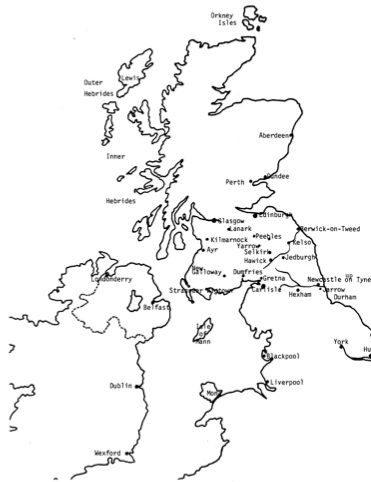

In this issue we include the up-to-the-minute membership list but have omitted the discography, list of pipe makers, suppliers, and references. For the geographically minded, and with thanks to Robbie Greensitt (proprietor of Heriot and Allan) we have corrected the names of two of the towns shown on our map in the inside cover. He writes, -…it should be Newcastle upon Tyne (without hyphens) and Berwick-upon-Tweed (with hyphens). The ‘upon’ indicates that the town or city is north of the river; ‘below’ means that it is south of the river; and ‘on’ means both sides of the river. – Our cartographer (Brian) didn’t realize this, as his original maps were made in the U.S.A. and showed that the urban sprawl of these two cities reaches both sides of their respective rivers, hence the labels he assigned on the map inside the covers of Issues 1 and 2! However, we now stand corrected (we hope) and trust you will enjoy and utilize this issue of the Journal. Just remember, whatever happens, keep playing your pipesl

————————-

COMMENTARY by A Few Smallpipers

LOWLAND AND SMALLPIPE SCRIPTURES AHEAD?

The term classical is a confusing one because it has so many different meanings, but as a label in a musical context it has come to mean that which is not folk, jazz, rock, or other popular music forms. To enthusiasts of Highland culture (and no doubt to the confusion of the Sir Thomas Beecham crowd) the term has come to apply to Piobaireachd, the Highland piping art that is so distinct from other forms of Scottish piping. To the Highlander the very word conjures a mystical image of the MacCrimmons of Skye, perched on the crags of their time-honored past, fingering their sad laments in the style handed down over the generations through a vocal script known as Canntaireachd. From the development of the theme, or Urlar, to the variations, and then to the return to the theme, Piobaireachd embodies the spirit of classicalism – “with emphasis on purity, objectivity, and proportion and conforming to a pattern of usage sanctioned by a body of literature [or Cannteareach, as the case may be].” With its ill arsenal of techniques, themes, and variations Piobaireachd and its repertoire lie beyond the realm of folk-piping, into the realm of classical piping. As a complete classical work, the Piobaireachd is quite a thing to behold, and ~ relationship to the Urlar brings to mind the way Pachelbel’s “Canon” relates to the “Welsh Ground”.

Having said this, we can appreciate the value of adjudication in Piobaireachd, since by its classical definition a high standard of playing is required (at least as high as that of the MacCrimmons) to faithfully reproduce the perfected work. Is it fair, however, to apply the same criteria to other piping forms, namely the CeoI Beg (and worse, to Lowland and smallpiping)?

While it is true that two or more Highland pipers playing together ought be of comparable skill and should agree on the settings and style, it is also true that the settings they choose to reproduce and their style of execution are not the end-all. In many instances they play medleys of tunes based on “standard” settings found in tomes originally produced for the benefit of the Crown’s Highland regiments (if you play for the Queen, it should sound like it!). A positive result of this is that Highland pipers the world over “speak” a common language and share a common repertoire. But this is outweighed by the large number of well-garbed clones who are functionally illiterate regarding music, not to mention their ignorance of Scottish culture. It is a shame that many of those who play the loudest, most ostentatious acoustical instrument in the western world are unaware of its versatility, historical role, or origin. Worse yet, some of these individuals believe that because they possess a room full of medals they are somehow musically significant, yet they couldn’t tell a piano player that although their music is written in a C-scale, it actually falls on a modal B-flat scale. They are unaware of the reasons for cross-fingering and are oblivious to the fact that, like the clarinet, they play a “transposing” instrument. They treat their practice chanters like garbage and often don’t (know how to) tune them. They don’t seem to know or care that their “traditional” repertoire is comprised of Lowland, English, Irish, as well as Highland tunes. At one time, many of these tunes enjoyed a full compliment of lyrics – making them songs.

We wonder how many Highland pipers actually care about these things, but you see, this is the problem: the piping world is a whole lot larger and more diverse than that represented by the Highland piping community, yet it finds itself having to tolerate the criticisms of so many unqualified loudmouths. That community could benefit from a bit of humility and tolerance, for the prevailing attitude among Highland pipers appears to be that other pipe forms are inferior to theirs. To some the title “Great (Large)” Highland pipe is confused with “Great (The Best)” Highland pipe.

All too often today’s Ceol Beg performances (solo, band, etc) amount to technicians executing musical settings that were standardized half a century ago, offering an illusion of a “traditional” classical music. The players not only revere these settings, they insist on ranking players through competition, in yet another illusion combining sand-box politics with notions of “traditionalism”. How many times have we heard, after an excellent performance, something like “he missed the last grip in the second part” or “that’s not the correct setting” or a groan of disapproval when vibrato is used. Those who don’t conform are ignored or waved away. A far more meaningful goal of competition would be in determining rank within a pipeband.

4

If you’ve read this far, then you may expect what’s coming. Among Scots smallpipers in North America, many are also Highland pipers, which is logical since both are Scottish instruments. One result is that there are now a lot of excellent smallpipers; the smallpipes are a pleasant indoor alternative to the practice chanter. The trouble is, some can’t shake their indoctrination, their standard settings – their scriptures.

And so we hear that they want to hold competitions! We feel that Lowland and Scots smallpiping needs no legitimacy beyond its own survival and ability to communicate music. There is no “tradition” of competition for the instrument, and each player “of auld” was an independent – the tradition seems to have been: make your own! And who would judge such a competition? – the audience?! Besides, we know of at least three fingering/gracing systems that work well on the smallpipes – is an “open” Highland player or judge qualified to judge a performance graced by, say, picotage techniques?

Holding Highland-style competitions for an instrument that many Highland pipers laughed at a few years ago seems hypocritical and has no other purpose than to establish yet another crowd of elitists, intolerant of those who would play in the folk, Lowland, or whatever idiom. We suggest that status-conscious pipers take up the Highland pipe, for within its community the mechanism for ‘greatness’ seems to already be well in place! Adieu to scriptures!

5

————————–

LETTERS

More Recordings and References

Dear Brian:

I received my first issue of the NAALBP Journal last night with great delight… I

can’t wait for the next. Great job!

Here are some other recordings to add to your discography:

Kathryn Tickell “On Kielder Side” -1984- Border Keep – Northumbrian

Also USA: Musical Heritage Society MHS 11235T

Kathryn Tickell “Common Ground” ? Black Crow BC 220 – Northumbrian

Alastair Anderson “Traditional Tunes” -1976- Front Hall FIffi08 – Northumbrian

Alastair Anderson “Dookin’ for Apples” ? Front Hall FHR020 – Northumbrian

Alastair Anderson “Steel Skies” ? Flying Fish FF 288 – Northumbrian

Alastair Anderson “The Grand Chain” ? Black Crow BC 216 Northumbrian

And some tune books to add to your list:

Peacock’s Tunes by John Peacock

Northumberland Piper’s Tune Books (Vol 1-3) by Northumbrian Pipers Society

Bewick’s Pipe Tunes arranged by Matthew Seattle

Charlton Memorial Tune Book published by the Northumbrian Pipers Society

Northumbrian Piper’s Duet Book by Neil Smith

Here’s another instruction book:

Fenwick, J. W., Instruction Book for the Northumbrian Small-pipes, Newcastle, 1931

Add these books to your list:

Reed Making Pamphlet by George Wallace

The Heriot and Allan Pipers’ Handbook by guess who

The Piper’s Despair by D. M. Quinn, 1980 (reed making for Northumbrian and Uillean pipes)

I’ve also enclosed a photocopy of a brochure on the Morpeth Chantry (Bagpipe

Museum). Have any members gone who can give us a first hand account?

Keep up the good work!

Sincerely,

Gordie Peters

221 Lancaster Street

Albany, NY 12210

March 15, 1991

6

————————

LETTERS (CONTINUED)

For the Record

We the undersigned are aware of three rare recordings made in the late 1960’s featuring the music of the Scots smallpipes, Lowland pipes, and Chamber pipes. The first is a tape made around 1969 by John Scott, formerly of the Detroit Highlanders pipe band. It is a collection of tunes played on a set of smallpipes in A, with verbal descriptions of the tunes and the pipes. The tape was made by Mr. Scott for Alex MacNeill, son of the ‘blind piper’ Archie MacNeill, who Mr. Scott asserts was also a player of the smallpipes. Among many other interesting comments made by Mr. Scott was the following:

"When you play these small pipes here, you develop, just as product of the instrument, some real different ways of fingering that you're not used to doing on the big pipes. But...the two are the same thing really because the chanter is just a practice chanter."

The second tape was produced by the Clan Hannay Society in 1969 and features Dr. David Hannay of Sorbie playing a bellows-blown Lowland pipe, sometimes to the accompaniment of the piano. The tape was collected by Alvan and Jean Donnan in the early 1970’s while on a trip to Wigtonshire; they had the priviledge of visiting the Hannay household and hearing Dr. Hannay play the Lowland pipes on several occasions in the early 70’s. The third tape was recorded by Sam Grier in the late 1960’s and saw very limited distribution, but is a collection of Highland, Hebridean, and original tunes played on the Scots smallpipes and Reel, or Chamber pipes – with chanter-style regulators with beeswax “fipples” or stops.

Here’s a very nice find – a recently printed tune book entitled The Morpeth Rant, compiled by Matt Seattle (Dragonfly Music, 1990) shows a promotional poster for a concert and dance – “Dancing to pipes and Fiddles” from May 27, 1938. The appended programme lists two players of the half-long pipes, G. Johnson and A. Gibb. Is that enticing, or what?

We should next like to comment on an assertion made in the recent and widely circulated book by R. D. Cannon called The Highland Bagpipe (John Donald Publishers Ltd., Edinburgh, 1988) which reads:

"...but a recent modern development is a Northumbrian pipe with a Scottish-style chanter, pitched in D, a fourth higher than the standard practice chanter. Invented by Colin Ross, the Northumbrian pipe maker, it has been taken up by some members of the Lowland Pipers' Society. The chanter can be fingered in the Scottish fashion, and the sound is distinctively attractive."

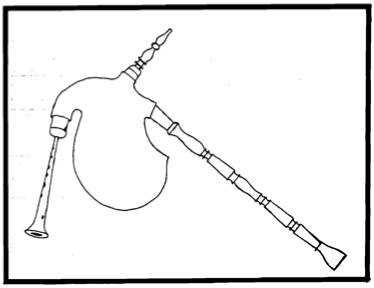

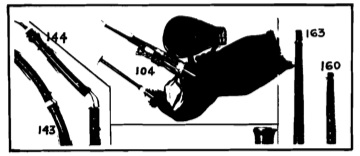

Are we to believe that Mr. Ross invented the Scottish smallpipe? Our information, via Alan Jones, is’ that Mr. Ross measured pipes located in various museums and proceeded from these measurements. Plenty of early smallpipes exist, and we point out just a few: In Cocks and Bryan’s book, The Northumbrian Bagpipe (Northumbrian Pipers’ Society, 1967) there are plans for an open ended chanter pitched in F which could be used with the shuttle drone or the long drones indicated on the page later. Further, there is a splendid photograph of a Scottish smallpipe in Ancient European Musical Instruments (Harvard University Press, 1941, Plate IV, #104) which contains photographs and descriptions of instruments housed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. A photograph of the instrument is shown below. The description of the instrument is as follows (page 93):

"Lowland Bagpipe - Scotland, 19th Century. Chanter and three drones. Leather bag covered with green woolen cloth, fringe on edges. Three stocks, silver tips. Drones of different lengths, conical bores of very small taper; silver and ivory tips. Chanter with cylindrical bore; seven finger-holes in the front, a thumb-hole in the rear. Bellows, length (bag and chanter),74 cm. Drones, short, bore, 4(3) mm; length, min.,17.3 cm; medium, bore, 4(3) mm; length, min., 24 cm; long, bore 5(3) mm, length, min., 34.3 cm. Chanter, bore, 3.5 mm; length, 19.5 cm. All lengths of pipes given without reeds.

"The Lowland bagpipe is a smaller Highland bagpipe inflated bellows. It is used mostly for dancing. As the name indicates, it is the instrument of the Scottish Lowlands. The drones are held either across the right arm or the right thigh, depending on whether the player stands or sits while playing. The scale of the chanter is the same as that of the Highland bagpipe. The sound of the Lowland bagpipe is less strident."

7

LETTERS (CONTINUED)

Further along this subject, Julian Goodacre wrote in recently and said he would be measuring the oldest set of Scottish smallpipes known – inscribed with the date 1757. A complete write-up by Hugh Cheape on this set appeared in the Common Stock (Vol 4, No.1, 1989, p.51). Finally, may we refer the reader to the set described by Alan Jones in the Journal of the N.A.A.L.B.P. (No.2, 1991), which was made in the late 18th/early 19th century and plays in C. How did Dr. Cannon miss all of this?

Lowland Smallpipe residing (as of 1941) in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Brian McCandless

Sam Grier

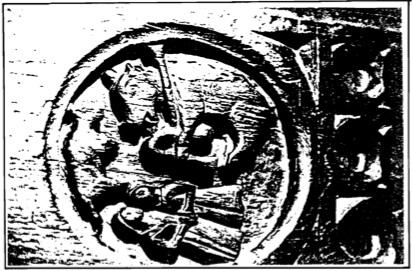

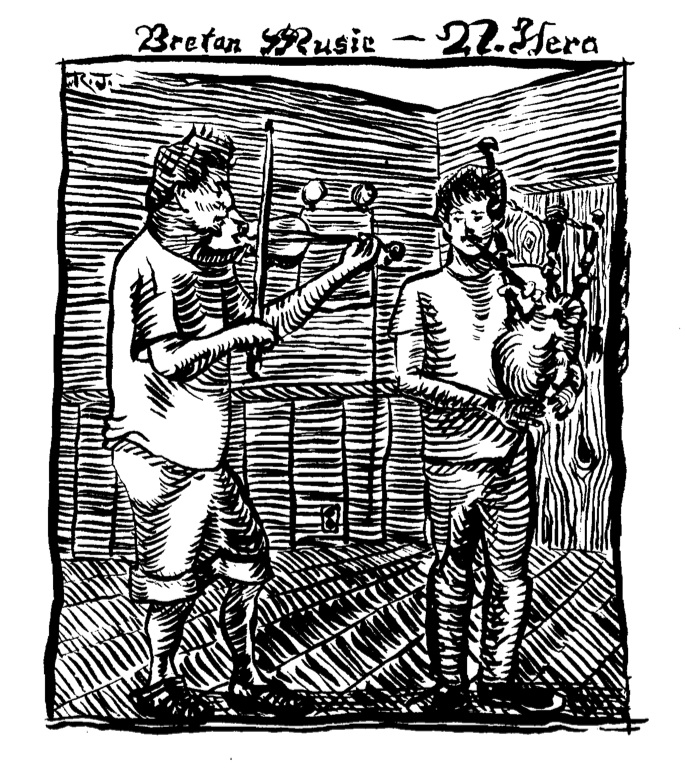

Pastoral Piper in its Musical Context

Can anyone identify this picture? It was featured on the cover of an issue of “The Musical Heritage Society” catalogue and appears to be of 19th century vintage. At first glance, one is tempted to say that the seated elderly gentleman is playing a set of Uillean pipes, but take notice of the chanter! It is extremely long, showing a foot joint, and there is a hint of a slightly flared sole. Also note that there are only two drones. This must certainly be a Pastoral pipe. Please feel free to offer your opinions or other information regarding this rare and wonderful picture to me or to the editor of the Journal.

Mike MacNintch

20 Pepperidge Trail

Old Saybrook, Connecticut

06475

—————–

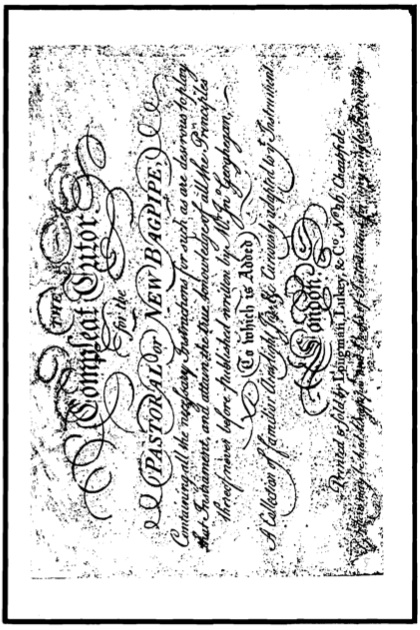

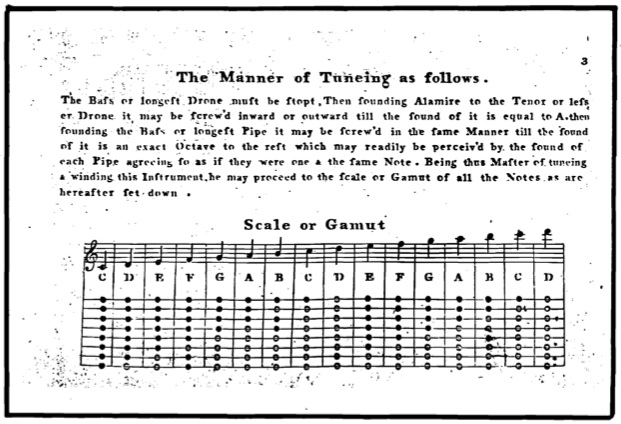

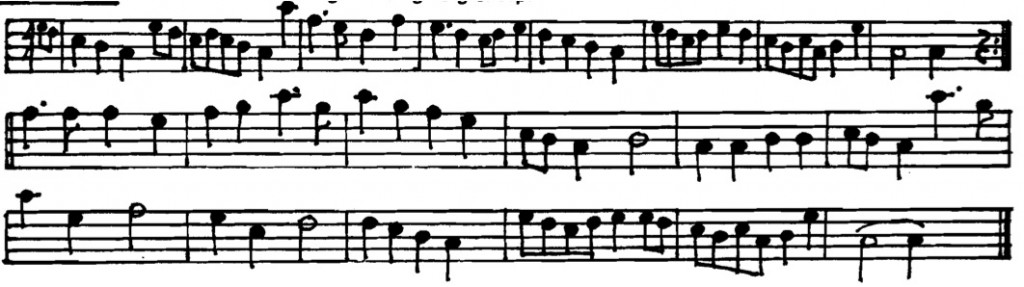

GEOGHEGAN’S TUTOR

At last, and as promised, we are reproducing the tutor section of John Geoghegan’s Compleat Tutor for the Pastoral or New Bagpipe. This copy came into the possession of the Editor through Alan Jones, who obtained it through the Irish Pipers’ Club in Seattle. This is a copy of a copy of a copy of the ‘Simpson Edition’ which was published c.1746. We have endeavored to enhance the lettering and to remove distracting photocopy marks. For ease of reading, we left the Tutor at the size we received it, and so to fit it we mounted it sideways in the Journal. The spiral binding will allow you to lay it neatly flat to examine it. In addition to the Tutor, we have added just a few remarks and a Table of Contents, which is lacking from our copy. Although we have already republished a couple of tunes from the Tutor in Journal #1, we do plan to republish all of the tunes, as they originally appeared, in a future issue.

———————–

[The copy of a copy of a copy of the tutor is difficult to read and will not be reproduced in full here. However, the pdf of the Original Full NAALBP Journal has the tutor mentioned. Download the full pdf HERE. If you would like an easier to read version, Ross Anderson has a high res scan of a different edition of the tutor on his website HERE.]

9

———————

Contents of Geoghegan’s Tutor – John Simpson Edition

Contents

Preface

A Treatise on the Bagpipe

The Manner of Tuneing [sic]

An Explanation of the First Scale

Of the Flats and Sharps

Of the Cadences or Shakes

…first Curl is Prick’d in Music

Of Pricks, Rests, and Pauses in Musick

Of Tyed Notes

A Scotch Measure – 8/8

Whip Her and Gird Her – 6/8

A Charming Nun to a Fryar Came – 4/4

Tweedside – 3/4

Dying Swan – 3/4

Gahagan’s Frisk – 6/8

The Mamina – 2/4

A Minuet – 3/4

The Red Lyon Hornpipe – 3/2

The Mayjor – 6/8

Ravencroft’s Fancy – 3/2

A Highland Rant – 8/8

New York, a hornpipe – 3/2

The Lass of Levinstone – 8/8

A Bagpipe Concerto called

The Battle of Aughrim, or Football Match – 8/8

Can Love be Controlled – 3/4

At the Brow of a Hill – 3/4

A Scotch Measure – 4/4

A Scotch Air – 4/4

The Humours of Westmeath – 6/8

Blab not what you ought to Smother – 3/8

By Men Belov’d – 4/4

Dan Gay – 3/4

Blind Paddy’s Fancy – 8/8

Chark’s Hornpipe – 3/2

New Mile End Fair – 4/4

Thump the Bitches – 8/8

The Chocolate Pot – 8/8

With Early Horn – 6/8

Let Me Wander – 2/8

Fly Swiftly Ye Minutes – 3/8

Cat’s a Monkey, or Sleg’s Hornpipe – 8/8

The King’s Head – 3/2

Six and Sevens – 3/8

Welsh Fair – 4/4

Castle Bar – 6/8

A Hornpipe by Mr. Lawrence – 3/2

Drunken Peasant – 8/8

Middle Row Harlequin – 6/8

Portsmouth Harbour – 3/2

Paddington Pound – 4/4

10

———————-

THE LINCOLNSHIRE BAGPIPE by John Addison

The following was compiled from a reprint of an article by John Addison (pipemaker) which first appeared in Prospect of Lincolnshire (1983) and some notes, photographs and computer-enhanced drawings he subsequently sent to this Editor, who wishes to thank Margaret Hall for putting us onto the original article. In the work, Mr. Addison has superbly documented the occurrence of bagpipes in Lincolnshire, England……..Lincolnshire, you say?

And why not! For it is well known that piping traditions were enjoyed throughout Great Britain and Ireland since the Mediaeval period. The carvings on stones and church pews discussed in this article are iconographically similar to those found in Lowland Scotland, for example, the 17th century carving of a piper on a panel in Kirkcudbrightshire (see plate 21 in The Traditional and National Music of Scotland, by Francis Collinson, Vanderbilt University Press, 1966), or the 15th century carvings of an angelic piper at Rosslyn Chapel in Midlothian or the elderly bagpiper in Melrose Abbey (see The Story of the Bagpipe, by Grattan Flood, Walter Scott Publishing Co., London, 1911, pages 46-50).

This article is the first of several we hope to include in the Journal regarding the origins of piping in Great Britain. On our inside cover map, you will find Lincolnshire located below the town of Hull – on a better map it would be south of the River Humber, northwest of The Wash, and east of Nottinghamshire.

The bagpipe as a form of musical instrument is of great antiquity. Though carried by the Romans (who are sometimes mistakenly credited with their invention) to many parts of their Empire, it certainly predates them. Whether it was the Romans who were responsible for the undoubted spread of the bagpipe westward, or whether it was brought earlier or later by nomads, wool traders, merchants or imported labourers is a Question which cannot be answered. It is quite possible that such instruments had been developed and were extant in particular localities.

I must confess to some trepidation on approaching the subject of the Lincolnshire Bagpipes, since the information which is available on them suggests that such an instrument did indeed exist but it is not sufficiently detailed to explain what form it took. We are unfortunate that the interest of the English Renaissance artist did not extend to rural festivities to the same degree as did that of the painters in the Low Countries. Their faithful attention to detail has allowed the reconstruction, with some degree of certainty, of instruments, including bagpipes, which have been extinct for some hundreds of years.

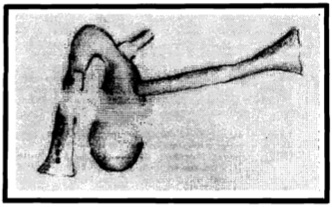

One of the earliest visual records of a bagpipe in Lincolnshire is the 15th century carving of a pew end in Branston church (Figure 1). This powerful but primitive motif gives at least some information; it shows a bagpipe with one chanter (melody pipe) which is probably conical, one drone with a bell end, and it is mouth blown. This description also covers pipes which would undoubtedly have been seen in an large part of Eastern Europe, most of Western Europe and some of Northern Africa and can still be seen in some of these places today. A point of interest about the Branston carving is that it depicts a bear playing the pipes. Dr. R.D. Cannon has these quotations from two centuries later:

If they hear the baggepipe then the bears are coming... (MS Bod!. No. 30 16b c. 1625)

A cittern is as natural to a barber as milk to a calf or dancing bears to a bagpiper. (Wooldridge, 1983.)

...the people run out to see them (Cromwelliam troopers) as fast as if it had been the bagge-pype playing along before the Beares. (Vox BorN/is, 1641.)

21

Figure 1. Carving from an oak pew end, Branston Church, Lincolnshire. Bear (?) playing pipes, two female figures, and an unidentified animal.

Another carving depicting a bagpipe, this time in limestone, comes from Moorby where it was built into the vestry wall of the·now demolished church. It shows a bagpiper and three dancers and probably dates to the late 15th or early 16th century (White, 1983, 111).

Figure 2. The Moorby Stone carving.

Figure 2. The Moorby Stone carving.

22

Possibly the earliest reference to the Lincolnshire bagpipe comes from Bishop John Bales in 1407; ‘It is right well that Pilgrims have with them both singers and pipers.’ (Parker Society, XXXVI, 102). Bale added a note in the margin, ‘Well spoken, my Lord, for the Lincolnshire Bagpipes.’

It is interesting to note that according to a play of 1590 there was current in London a song entitled ‘The Sweet Ballad of the Lincolnshire Bagpipes’, though the song is now lost. Probably the most quoted and most obscure literary reference is from Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1, Act one, Scene Two:

Fallstaff:'Sblood, I am as melancholy as a gib cat or a lugged bear

Prince Henry: Or an old lion or a lover's lute

Fallstaff: Yea, or the drone of a Linconshire bagpipe

Another regularly cited reference comes from Robert Arin, an actor in Shakespeare’s company in An Nest of Ninnies, 1608, describing a banquet held that year:

At Christmas time, amongst all the pleasures provided, a noyse of minstrells end Lincolnshire bagpipe was prepared -the minstrells for the great chamber, the bagpipe for the hall -the minstrells to serve up the knights meate, and the bagpipe for the common dauncing.

Michael Drayton (1563 – ‘631) remarks in Blayzons of the Shires:

Bean-bell Leicestershire her tribute both beare And Bells and Bagpipes next belong to Lincolnshire Whose swains in Shepherd's gray and girls in Lincoln green, While some the ring of bells and some the bagpipes ply, Dance many a merry round and many a hydegy.

A number of late 16th and early 17th century inventories mention pipes amongst personal belongings of men described as ‘pipers’. Unfortunately, the use of the term ‘piper’ to refer specifically to a bagpiper is 19th century in origin and the pipers of these inventories may have played recorders or similar instruments. However, the inventory of Hugh Artie of Pinchbeck, ‘pypar’, dated 2 February 1582/3 (LAO LCC Admon. 1582/21) who had goods valued at £11 11s 6d including ‘ij pare of pypes..ijs.’ This may be a reference to a set of bagpipes. (I am grateful to C.J. Sturman for bringing this inventory to my attention.)

On the rare occasion when Lincolnshire bagpipes are mentioned there is difficulty in accepting that any contemporary commentators were at all qualified to give even the broadest description of the instrument. The following description by Thomas Fuller in Worthies of England (Fuller, 1642) is possibly such a case:

Lincolnshire Bagpipes. I behold these as most ancient, because a very simple sort of music. being little more than an oaten pipe improved with a bag, wherein the imprisoned wind pleadeth melodiously for the enlargement thereof. It is incredible with what agility it inspireth the heavy heels of the country clowns...This bagpipe, in the judgement of the rural Midases, carrieth away the credit for the harp of Apollo himself; the most persons approve the blunt bagpipe above the edge-tool instrument of drums and trumpets in our civil dissensions.

As his remarks seem somewhat biased against the county people and their dances and music, it is difficult to evaluate his description of the bagpipes. An ‘oaten pipe’ is just what the name implies, a length of oat straw is cut to form a tube, one end of which is gently chewed to produce a flattened shape which is, in effect, a double reed. Finger holes are cut in suitable places and the instrument thus produced is a rudimentary double reeded, cylindrically bored chanter (Figure 3). This instrument was in common use by shepherds in France as late as 1840 as a practice chanter for the cornemeuse (Sand, 1840) and has recently been made in my own house by a bagpiper from Toulouse. There can be little doubt that the same was the case in England. Fuller’s description, therefore, presents something of a puzzle, in that the sound of a chanter with a cylindrical bore is very distinctive, quite refined and far removed from the ‘mighty barbarous’ sound referred to by Pepys, another much quoted source. Unfortunately, this brings to light another problem. Wheatly’s transcription of Pepys’ diaries (Wheatley, 1896) mentions the Lincolnshire bagpipes by name.

23

Latham and Matthews (1976) transcribe the same passage as ‘…called for his bagpiper’. It seems possible, that Wheatley put together Lincolnshire and bagpiper by supposition rather than with sound reason. An article on the ‘last Lincolnshire Bagpiper’ appeared in 1881 (LNQ, 1881 ):

John Hunsley was a player on the bagpipe up to a short time before his death which took place between 20-30 years ago [i.e. 1850-60). The music emitted from John Hunsley's instrument was ~ certainly unmelodious but it pleased him and many of the people amongst whom he lived.

Canon P. Binnall had further information on John Hunsley, remembering a narrative from Dr. G.F. George who was then about eighty years old and had, earlier in his life, the general practice which covered Manton, where Mr. Hunsley lived. Dr. George was told the story by patients he visited as a young man:

John Hunsley, a farmer from the northern end of the parish of Manton...held riotous parties at which the guests removed their shoes and always danced until the brick dust came through the soles of their feet, to the accompaniment of their host's bagpipes...and I was told that once a year he rode to Edinburgh to have his pipes tuned.

Dr. R. Pacey, to whom I am indebted for the above information, located the deserted farmhouse where John Hunsley lived at Middle Manton and the brick floors are still in evidence but my own enquiries among pipe makers in Edinburgh have failed to suggest anyone to whom he may have taken his pipes, which therefore precludes any hope of information as to their nature.

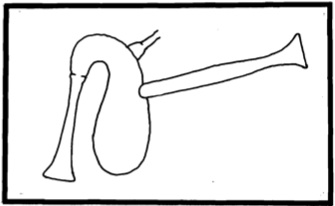

“Unmelodious” is not an uncommon description of the sound of bagpipes by listeners who are not used to it. It is also a reasonable comment if the chanter has a specific fingering system (as is usually the case) which is not used. This makes the instrument play out of tune and is particularly noticeable on chanters with a conical bore. Whether any of the above accounts are absolutely accurate, partially correct or just oblique comment, I feel that they give the impression of an instrument, the closest relative of which is, and possibly was, the Spanish Gaita Gallega. This is still the simplest, or at least the most straightforward form of the bagpipe in Europe and has not changed in centuries. (Figure 4).

24

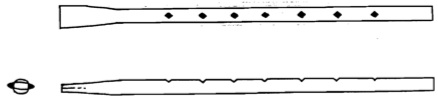

Figure 4. The Spanish Gaita Gallega, a simple form of bagpipe.

Figure 4. The Spanish Gaita Gallega, a simple form of bagpipe.

There are various other attributions for the name ‘Lincolnshire Bagpipes’, such as the croaking of frogs in the fens; the local worthies of the present are generally convinced that the term arises from their boyhood game of holding a tomcat under one arm and coaxing it to ‘sing’ by biting its tail.

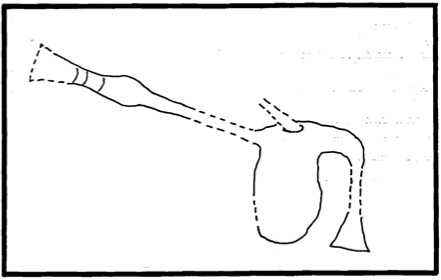

I give the reader this thought I am a maker of bagpipes (Northumbrian, Irish, Scots and French) and I am a native of, and work in, Lincolnshire. Had I been alive 250 years ago and pursuing the same occupation, what would present day historians have made of it? Though I am not a maker of Lincolnshire bagpipes I am a Lincolnshire bagpipe maker. Along these lines, I have been asked to make a set of Lincolnshire pipes, which I finally agreed to do. I used the Branston Church carving and the Moorby stone to guide my work, and was aided by computer enhancement of the original photograph of the Moorby stone carving.

For scalar comparisons, the Branston carving (Figure 1) is too approximate. for example, what is the type and size of the animal playing the bagpipe? For my own interest, however, I overdrew a photograph of the instrument and had the drawing enlarged and reversed (Figures 5,6). Though the scale of the chanter to bag to drone length does not match the Moorby stone, the general feeling of the instrument in remarkably similar, if one makes some allowances for artistic license.

25

Figure 5. A careful derivation from the Branston Church carving.

Figure 5. A careful derivation from the Branston Church carving.

Figure 6. Line drawing based on derivation of Branston carving shown in Figure 5.

Figure 6. Line drawing based on derivation of Branston carving shown in Figure 5.

26

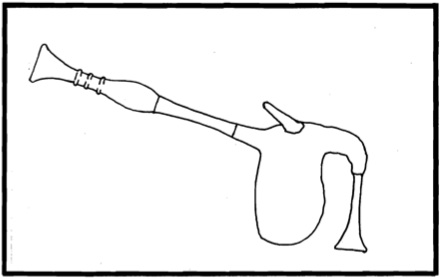

The Moorby stone (Figure 2) provided the basis for the instrument which I constructed. In addition to the original chanter, I constructed a second one based on the description given by Thomas Fuller, as it does not match up with the above instrument. If Fuller had any working knowledge of musical instruments, the bagpipe he describes would necessarily have a cylindrical bore in the chanter. This is the difference between the two chanters I have made. The cylindrical chanter plays one octave below the conical chanter.

Using computer enhancement of a series of photographs of the Moorby stone carving (Figures 7, 8, and 9), I came to the following assumptions with regard to the scale of the instrument, relative to the size and accuracy of the Figure.

The general stance of the figure gives the impression of being posed – possibly for a preliminary drawing by the carver? The fact that only one hand is on the chanter, while the other supports the bag suggests this. If it were taken that this was the method of playing the instrument (one hand pressing the bag), the compass of the chanter could be no more than six notes. More notes could be available by making the chanter jump the octave, but this would not form a consecutive scale and would be almost useless musically. In my experience the six note compass does not relate to any other form of musical instrument, or music, which uses Western musical conventions.

The shape of the drone suggests a two piece tube, the bulge half way along it relating well to the tuning slide quite usual for this design throughout Europe, both presently and historically. The length, by scale, to the figure, is approximately 22″ to 27″. By averaging the bore dimensions of which I have experience, I would expect a drone of this size and from to play somewhere about F, G, A, or Bb. To play F, the drone bore would be relatively small and would thus give a quiet sound, suitable for the accompaniment of a quiet chanter (with a narrow conical bore). To play A – Bb, the drone bore would be quite larger and thus give more volume, necessitating a loud chanter for balance, that is, a chanter with a wide conical bore. Such a bore would not only raise the volume, but for the same length as above, raise the pitch to, say, A or Bb. I chose the key of G.

The chanter on the carving is too unclear to furnish much information other than to suggest a conical form of approximately 13″ to 15″ in length. This, however, tallies reasonably well with the estimated pitch of the drone. With a narrow conical bore and sound holes spaced naturally for the fall of the fingers, I would expect the pitch, with an average reed form, to be somewhere around F. I chose 14″ as the optimum chanter length, with a bore of medium taper. The hole spacing for the correct tuning of the diatonic scale of G falls easily under the fingers of adult hands.

Figure 7. The piper seen on the Moorby stone.

27

Figure 8. Tentative outline of the Moorby stone bagpipe.

Figure 8. Tentative outline of the Moorby stone bagpipe.

Figure 9. Final form of the Moorby stone bagpipe.

Figure 9. Final form of the Moorby stone bagpipe.

28

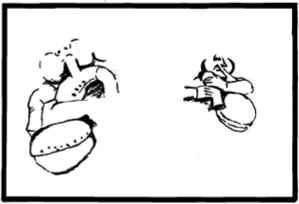

On the top of the bag in the carving, there appears to be a scar in the stone where I would estimate a blowpipe might have been. I suggest that this, as a fragile component of the carving, may have suffered the same fate as the piper’s facial features. The bag is of very familiar appearance. Sometimes, in areas where goat or sheep farming is, or was, of importance (as in Lincolnshire), complete animal skins are, or were used. The back end is tied or stitched up, while the front legs and neck accommodate the blowpipe, drone, and chanter respectively. This is not the case here, for the shape gives an indication that this is a fabricated bag. This is not unusual for the period or style of the instrument -contemporary or even earlier carvings in Beverly Minster (Figure 10) show clear representations of seams and stitching on the bags of bagpipes.

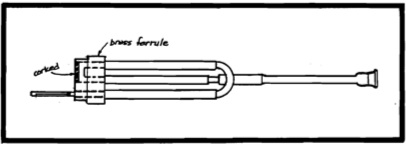

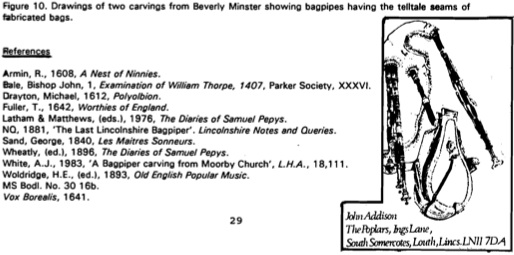

EARLY UNION PIPES by Denny Hall

The following notes were sent to us by Denny Hall regarding an old set of Union pipes by Egan which he had borrowed from Mick Zekley. The notes were originally published in the Pipers’ Review by the Irish Pipers’ Club in Seattle. We have added a photograph of a recent reproduction of an Egan instrument by Steafan Hannigan (London) to augment the description given by Denny (with many thanks to Mike MacNintch, who photographed the set at the 1991 Round Hill Scottish Games).

If you are interested in contacting the Pipers’ Club, their address is:

Cumann Na b 'Piobairi P.O. Box 3183 Seattle, Washington 98103-1183

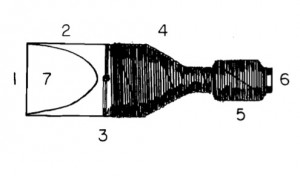

This set is a good, original representation of the early evolution of the Union pipes. The chanter is stamped EGAN. There is no reason to believe that the entire instrument is not the work of Egan. The pipes are very nicely turned boxwood, decorated with ivory. While many instruments of this vintage (last third of the 18th century) have only two drones (see O’Neill’s Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Chicago, 1913, p. 44), a baritone and bass, this particular set has also a tenor drone and a small drone to sound an A. The instrument is a ‘D’ set and has one regulator with only four keys.

With the exception of the tenor and small A. drone, this set is very much like the early (and contemporary) Union pipe with the 20.0 cm foot-joint on the chanter described by Denis Brooks in the Pipers’ Review (Vol. 1, No.2). This type of pipe has been referred to as the New Pastoral Pipe and Long Pipes. Anthony Baines (in Bagpipes, Pitt Rivers Museum, 1960, p. 123) quoted William Cocks (c.1954) and also referred to this long chanter bagpipe as “Hybrid Union Pipes”. The chanter with foot joint necessitated playing off the knee; its [only] advantage was that a low C (c’) was available.

I have some snapshots of another set in Mickie’s possession, similar to this Egan set, built of the same materials with three drones and a five-key regulator. Despite the additional key, the regulator appears to have nearly the same length as the four-key regulator.

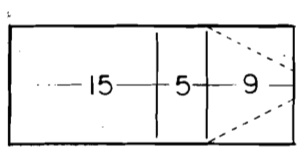

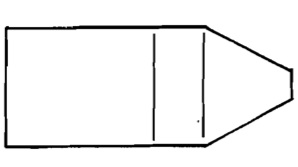

The diagram following is of perhaps the most unique feature of this instrument. The drawing (Figure 1) shows the bass drone recurving through the stock, with the result that it is but two or three inches longer than the baritone drone. The stock which holds the pipes, in turn, fits into a hollow main stock the size of which we are familiar with. Although this arrangement allows for an extremely compact bass drone, it eliminates the possibility of a convenient drone switch as we know it.

Figure 1. Drawing of the bass drone arrangement on the Egan Union pipe.

Figure 1. Drawing of the bass drone arrangement on the Egan Union pipe.

30

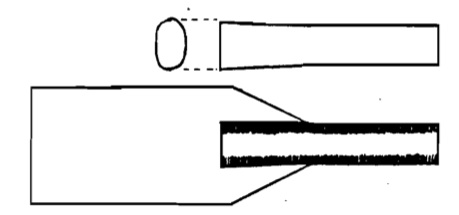

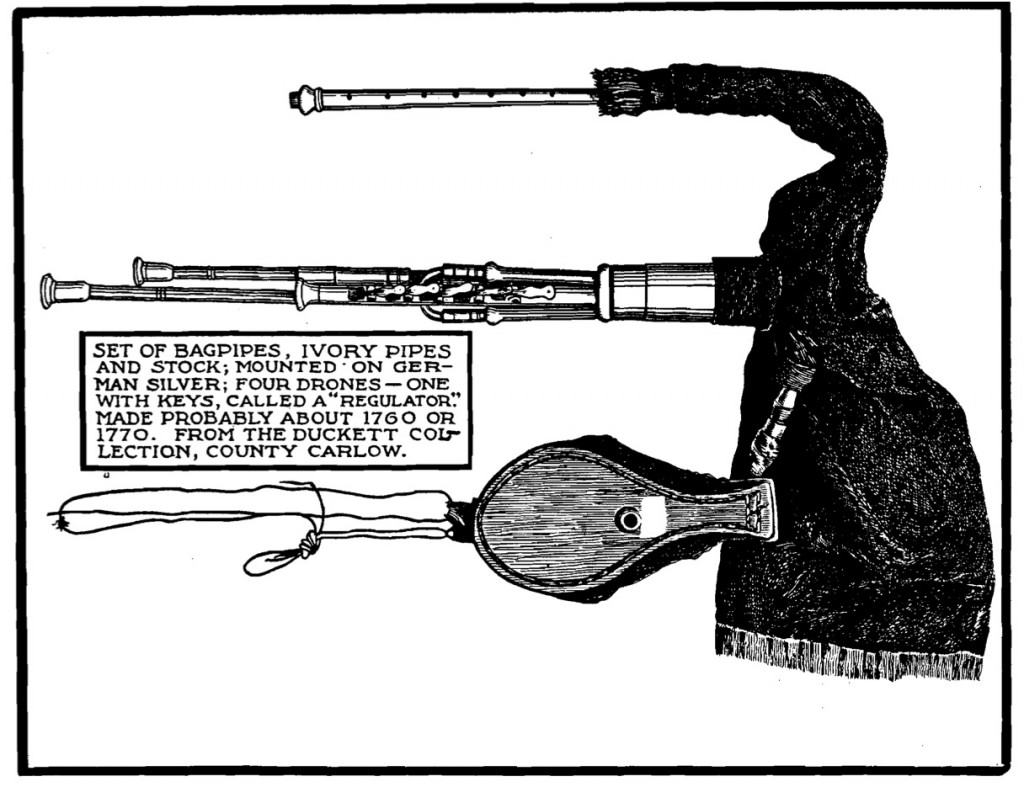

Below is a photograph of a set built recently by Steafan Hannigan, having four drones and a four-key regulator. The drone stock has been separated from its cup to show the reeds. The maker installed a drone switch by locating it at the base of the drone stock. The set plays in C# and is shown with a D chanter.

Figure 2. Union pipe built by Steafan Hannigan of London to a design by Egan.

Figure 2. Union pipe built by Steafan Hannigan of London to a design by Egan.

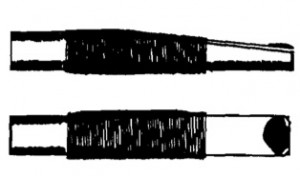

Finally, here is a photograph of the drone stock for the Egan instrument (see also Figure 3 in the article by Sam Grier in Journal 2, 1991, page 151). In Figure 3 below, the fourth drone reed is just visible behind the small ‘0’ drone reed. The regulator reed is on top.

Figure 3. Detail of the drone stock on the Egan Union pipe.

Figure 3. Detail of the drone stock on the Egan Union pipe.

31

Early Union Pipe, from Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Francis O’Neill, 1913.

SET OF BAGPIPES; IVORY PIPES

AND STOCK; MOUNTED· ON GER

MAN SILVER; FOUR. DRONES – ONE

WITH KEYS, CALLED A “REGULATOR:’

MADE PROBABLY ABOUT 1760 OR

1770. FROM THE DUCKETT COL

LECTION, COUNTY CARLOW.

Early Union Pipe, from Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Francis O’Neill, 1913.

——-

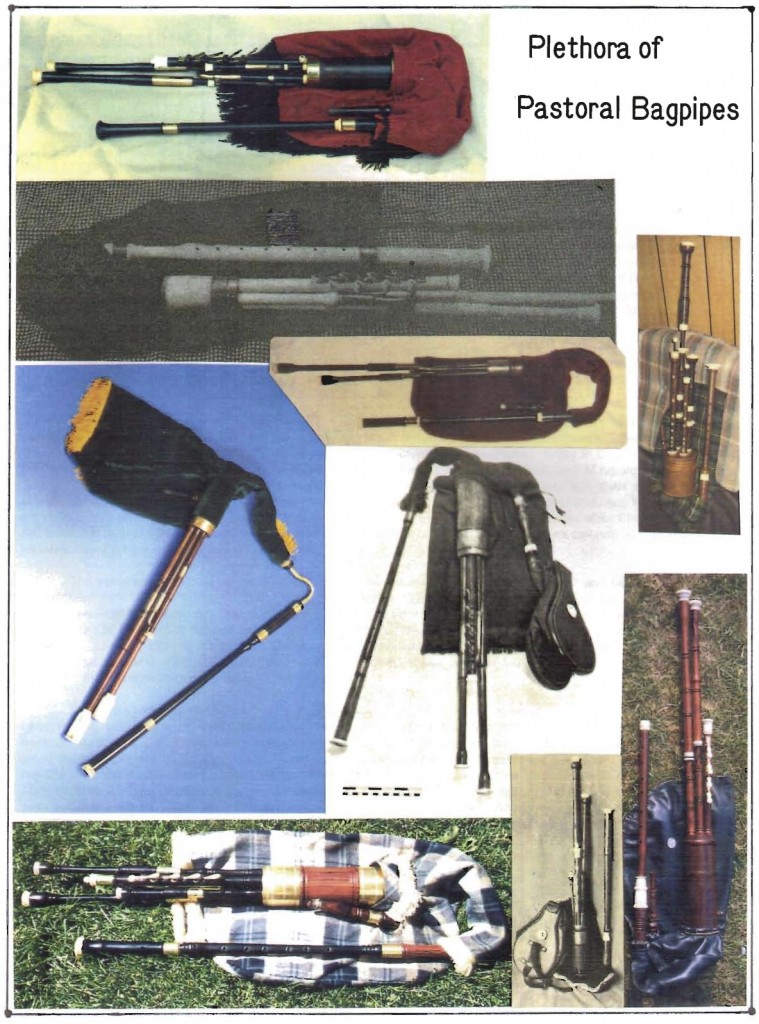

PLETHORA OF PASTORAL BAGPIPES – DIRECTORY

1. Blackwood and brass, three drones, one regulator, Eb or D, c. 1800, partially restored by Colin Ross, owned by Alan-Jones. Photo by Brian McCandless.

2. Ivory, two drones (?), one regulator, c. 1750, as advertised in Lark in the Morning Catalogue around 1982. Sadly, this rare set was destroyed in a house fire three years ago. Our thanks to Mickie Zekley for permission to use the photograph.

3. Blackwood and brass, two drones, no regulator, Eb, c. 1982, made by Colin Ross, owned by Sam Grier. Photo by Sam Grier, used by permission.

4. Reel pipe described in Journal #2, two drones, two regulators, Bb, made by Sam Grier.

5. Cherrywood and speckled walrus ivory, three drones, no regulator, Eb or D, c. 1790, partially restored, owned by lain MacDonald. Photo by lain MacDonald, used by permission.

6. Boxwood and brass, two drones, one regulator, D, date unknown, fully described by Baines in Bagpipes, 1960. p. 123.

7. “Early Union Pipe” after Egan’s design, two drones, one regulator, recently made by Steafan Hannigan. Photo by Mike MacNintch, used by permission.

8. Exact copy of Naughton’s pastoral pipe (1826) now residing in the Kinguissie Museum, three drones and one regulator, Eb, made by Chris Bayley c. 1980. Thanks to Hamish Moore for permission to use the photograph.

9. Blackwood and brass, three drones, one regulator, D, made by John Addison c. 1980, owned and kept in playing order by Sam Grier. Photo by Mike MacNintch, used by permission.

32

Plethora of

Pastoral Bagpipes

33

MAYPOLES, MORRIS DANCE, AND BAGPIPES by Brian McCandless

“This is it and that is it,

And this is Morris Dancing,

The piper fell and broke his neck,

And said it was a chancer. “

I first came across this little jingle a few years ago while reading through Cecil Sharp’s The Morris Book, Vol. 3 (1924). The reference to a piper (is it a bagpiper, a whistle player, a hornpipe player?) in the context of the Morris dance intrigued me and subsequently led to an investigation which produced some simple and not surprising conclusions: 1) the ritual dances of Britain are related to those formerly found in Germany, France, and the Low Countries; 2) the ritual dances are geomantic in nature and descend from “iron age” communal celebrations which focused on fertility themes; 3) the music for these dances was performed on the instruments available at the time; thus 4) sometime around 1300 AD, the bagpipes were adapted to this ritual dance setting. In this article I will present evidence to support these conclusions, drawing upon artistic works, literary quotations, melodic analysis, and culture history. I will also discuss how Lowland pipes can be used to perform music for May dancing, Morris dancing, and other exhibition or participatory dances. In the past few years, I have had the pleasure of using the Lowland pipes to perform with a Welsh folk dance group called Dawnswyr Y Tract Cymreig (Welsh Tract Dancers), based in Newark, Delaware.

Ritual Dance

So what do we mean by ‘ritual dance’? For our purposes, we use the term to refer to exhibition dances performed by a trained ‘elite’ or ‘select few’ as part of the focus of seasonal community celebrations. Into the cauldron of ritual dances which have survived or evolved to be performed today in Britain we find the Morris dance, the Cornish processional dances, Horn dances, the Sword dances, and Maypole dances. Today, unlike in former times, these dances are performed throughout the year, but their seasonal associations have not been lost. For example, the Sword dances of Durham, Northumberland, and Yorkshire are still performed around Plough Monday (the Sunday after the Epiphany, or twelfth night after Christmas). So, the ritual dance differs from other folk dance forms, such as ball room dancing, by its calendrical ties and its performance by a select group of specialists.

The occurrence of ritual dance in so-called ‘primitive’ societies is well documented and serves many complicated functions. But perhaps the most important of these is to serve as a vehicle for linking the spiritual world to the physical world. We have all no doubt seen the documentary footage by Franz Boas (c. 1950) of the ritual shaman dances of the Kwakiutl peoples of the American Northwest in which the shaman, in god-like disguise, dances a repetitive series of fixed movements designed to invoke the gods of the sea, the sky, and the earth. Other Kwakiutl dances are performed at sea on great log boats whose purpose is to transport the shaman dancer directly to the sea god.

To bring this home to Britain, we must take stock of our best notion of earlier cultures in Britain, and observe the occurrence of ritual folk dance, as it was before the age of mass communication and homogenization. We can envision Britain as a sort of ‘last stop’ melting pot for European cultural migrations since the neolithic period (c. 2500 BC). These cultures variously exerted dominance over their ‘conquered’ regions until the next influence came along. With the exception of destructive Viking coastal raids of the 10th century AD, the pattern of cultural invasion was characterized by integration of the ‘invading’ culture with existing peoples. From each infusion a new ‘culture’ was established, incorporating the ways of both. At different times, Celts, Danes, Saxons, Angles, Normans, and others have asserted themselves upon the ‘native’ culture. Archaeologists have determined that a common theme to pre-Christian British inhabitants was fertility, and among the customs associated with this theme was dancing. Aubrey Burl, the noted British prehistorian writes (The Stone Circles of the British Isles, Yale Press, 1976, p. 84):

“….Stone circles are unlikely to have been temples of the mother-goddess. The activities within them were more probably directed towards fertility practices.

34

“That these included dancing is an assumption that cannot be proved although such communal activity is well,recorded among primitive societies. Frazer (1922) gives many examples of ring-dancing around a Maypole in Europe at the leafing time; around bonfires at Lent when, in parts of Switzerland and elsewhere, burning wheels like sun-discs were rolled down hills and when witch effigies were burned on hilltops. In the Isle of Man a wren was killed at the Winter solstice and buried after which the people would dance in a ring to music. Such circular group-dances were clearly customary at important divisions of the year.” So let us describe some of the British ritual dances as they exist today.

Mumming Play: In many English, Scottish, Welsh, Cornish, French, German, Low Country, Austrian, and Swiss villages a kind of life/death/resurrection play or mime has been carried out for centuries during Yuletide and May Day celebrations. The ‘actors’ dress in costumes based on mythical figures which may include Santa Claus, St. George, Robin Hood, Maid Marian, the Hobby Horse, the Fool and others. The ultimate in Hobby Horses would appear to be that at Padstow, Cornwall, while Santa Claus and Father Winter are taken to extremes in Bavaria and Switzerland. In many mumming traditions, the ‘play’ is performed according to a strict ritual code and is closely tied with the ritual dances. According to Charles Kightly, “‘Mumming’ may be derived from Germanic Mummen – a mask; or French Momer – to act in a dumb show. Either is appropriate, for mummers still conceal their identity (in Scotland and northern England, indeed they may be called ‘guisers’) while many of their activities were concealed in silent mime.” The central themes of birth, death, and rebirth are acted out with familiar folk heroes and villains. In England, one of the first accounts of a mumming play was related in London, in 1377, in the court of Richard II. Today’s expression “mum’s the word” derives from the act of “mumming” or “miming”. The wildly ostentatious mumming events held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania appear to be a glitzy derivative of this pan-European tradition.

Sword Dance: Performed around Christmas time, in Yorkshire, Durham, and Northumberland in a type of Mumming Play involving five, six, or eight men. According to Charles Kightly, “The ceremony begins with the dancers walking round in a circle, in some versions clashing their swords together: then they place these over their shoulders, each man grasping the point of the sword in front of him with one hand. while keeping hold of his own hilt with the other. Next, the swords are lowered to waist-level, so that the dancers form a ring, linked ‘hilt and point’ by their weapons…always maintaining their grip on their own and their neighbor’s swords, the dancers then perform a series of complicated figures…as a culmination, the swords are ingeniously woven together in a pentagonal, hexagonal, or octagonal star which is held aloft for display.” Variations exist, and in the ‘Longsword dances’ of Yorkshire, after the Lock is made, it is dropped over the head of ‘The Fool’ until it rests about his neck. “Then, at a given signal, the dancers suddenly and simultaneously withdraw their swords, whereupon the ‘victim’ falls ‘dead’ to the ground. In Northumberland and Durham, where the dance is called the ‘Rapper dance’, after the thin, sharp rappers used, the possibility for real beheading necessitates a gentler approach – the dancers symbolically lower the Link or Knot over the head and lift it again.

Morris Dance:In former times, the word ‘Morris’ embraced ‘Morris dancing’ as we think of it today as well as Horn dances and the Mumming Play. The essential features of the modern Morris dance are best described by their longtime documentor, Cecil Sharp (1912): “The Morris dance, being a spectacular, not a social dance, was performed on special occasions only, and very rarely more than once or twice a year. In Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, Whitsuntide [literally, ‘White Sunday’ a popular spring day for Baptisms, being fifty days after Easter Sunday] was the recognized season for the performance of the dance. In Worcestershire and Herefordshire, however, where the dance still survives, albeit in a state of decadence, it was performed at Christmas time…the usual custom was for the dancers to rehearse one or more nights a week between Easter and Whit Sunday, when the older men polished up their own steps and instructed the new members of the team [or Side] in the mysteries of the art.

“The Whitsun celebration was often ushered in with some ceremony…at three o’clock in the morning on Whit-Monday three youths went out and cut withies, the bark of which they rolled up into funnel-shaped horns, called ‘peeling’ horns, pinning the bark together with the thorns of the blackthorn. By means of a double reed of willow, which was fitted into the narrower end, the horns emitted a penetrating, rasping sound, as loud as hooters. Roused at four o’clock by this strange music, the villagers assembled at the village green to assist in the raising of the Maypole. This, which had been previously prepared, consisted of a stout pole about twenty feet long, to the top of which was attached a thinner pole of about the same length, the whole being profusely garlanded with ‘Iaylocks and golden chains.’ Directly the pole was placed in position the Morris men danced round it.”

35

Although the Morris tradition is very rich and diverse, very often the first dance was always the ‘Green Garters’; later a procession would be held, led by a ‘mock’ mayor; and then the Morris dancers would dance from house to house and farm to farm throughout the district, even to neighboring villages. In 1600, a William Kemp danced the Morris dance from London to Norwich, later documenting it in his The Nine Daies Wonder. The traditional Morris costume is very elaborate and includes a hat, pleated shirts, bells, sticks, and handkerchiefs. An extreme variation of the Morris dance is the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance (Figure 1), danced on the Monday after the Sunday following September 4 (Wakes Monday). In this ceremony, there are ten dancers, six horn-bearing dancers, and four actors, dressed as ‘Maid Marian’, the Hobby Horse, a boy, and a Fool.

Figure 1. The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance -an annual Staffordshire harvest tradition for nearly a millennium.

A hodgepodge of these and other customs may be viewed (to the accompaniment of the Northumbrian smallpipes) in the 1973 film, The Wicker Man, written by Anthony Shaffer and directed by Robin Hardy. Invoking the subject of fertility allows us to focus on specific occasions when an agricultural I communities would be most sensitive, such as nuptials, sowing, and reaping. Studies of the customs and lore of modern Celtic peoples in Wales and Ireland, initiated in the early part of the twentieth century by Lady Jane Francesca Wilde and carried on recently by Alwyn and Brinley Rees (Celtic Heritage, Thames and Hudson, 1961) have isolated the significant features of the Celtic calendar and link it to an Indo-European heritage that reaches back to the European iron age.

36

The modern year is divided into four segments called seasons which are defined by the position of the sun along the ecliptic. The point at which the sun’s path crosses the celestial equator on its way north is called the vernal (from Latin: vernalis meaning spring) equinox. On the equinox, the day and night are of equal length, and the sun rises due East and sets due West. 182 days after the vernal equinox, the sun crosses the celestial equator heading south, on the autumnal equinox. Halfway between these days the sun reaches its farthest points north (summer solstice) and south (winter solstice). For many days around the solstices, the sun rises and sets at nearly the same location on the horizon, from which we get the term ‘solstice’ – “sun standing still.”

Curiously, the Celtic year begins midway between the autumnal equinox and winter solstice, on Samhain (Hallowe’en). The year was divided into two major seasons – summer and winter – called Samon and Giamon, marked by the festival days Beltaine and Samhain. Halfway between these days lie the festival days of Lughnasa and Imbolc. Together, the four festival days are called the ‘Quarter Days’. In a variation of the Celtic calendar called the Coligny Calendar, which amounts to a ‘timetable of ritual’ found in Gaul, the year was 60 months long, with each month divided into a ‘dark half’ and a ‘light half’. Two types of month were employed, six with 30 days and six with 29 days. At the beginning of each half-eycle, an intercalary month was inserted to adjust the intervals, which is among the oldest surviving calendar systems, having parallels in ancient Greece and India.

Below is a table listing the Celtic festival days:

| Approximate Date | Season/Event | Celtic Quarter Day | Christian Name |

| 31 October | Autumn | Samhain | Hallowe’en |

| 21 December | Winter Solstice | – | Midwinter |

| 1 February | Winter | Imbolc | St. Brigit’s |

| 21 March | Spring Equinox | – | – |

| 1 May | Spring | Beltaine | May Day |

| 21 June | Summer Solstice | – | Midsummer |

| 1 August | Summer | Lughnasa | Loaf Mass of Lammas |

| 21 September | Autumnal Equinox | – | – |

Recent linguistic studies by Colin Renfrew (Archaeology and Language, Cambridge Press, 1987) show that a common cultural origin is shared for the European language (hence culture) groups. Indeed, the very words naming the Celtic Quarter Days are considered to be vestigial remains of the proto-European language! For example, Lughnasa is named after the Celtic deity, Lugh, who was the giver of the harvest to people. The word serves as the basis for Lyons (France) which was known to the Romans as Lugudunum. The relationships between the Celtic (and proto-Celtic) pantheon and solar and lunar phenomena, the agricultural seasons, and the Earth itself are fairly well established. These findings lend credence to statements made by folklorists such as Charles Knightly (The Customs and Ceremonies of Britain, Thames and Hudson, 1986) regarding the origins of British ritual dance:

“[Morris dancing] in all probability, then, is older than its name: the latter being clearly well established in England by the time of its earliest known mention in 1458, when Alice de Wetenhalle (a London widow with Suffolk connections) bequeathed a silver cup engraved ‘cum moreys dance’. Just how old the dance is, however, cannot be even approximately estimated: though current thinking leans towards the view that – like the other form of ‘morris’, the mumming play – the dance originated as a pre-Christian fertility or luck-bringing ceremony, and it is even possible that the name ‘moorish’ once alluded to its pagan rather than its black-faced associations.”

37

“…This universality suggests that sword dancing long pre-dates the present racial structure of Europe: and attempts have been made to associate it with a prehistoric priesthood of smiths or iron workers.”

We should point out that a separate, solo, sword dance is performed in the Highlands, and according to R.D. Cannon (The Highland Bagpipe and Its Music. John Donald Publishers Ltd., Edinburgh, 1987) it first appeared at competitions in 1832 and, ·unlike some other Highland dances it appears to have been a genuine folk dance and was spoken of at the time as ancient.”

Bagpipes in the Morris Tradition

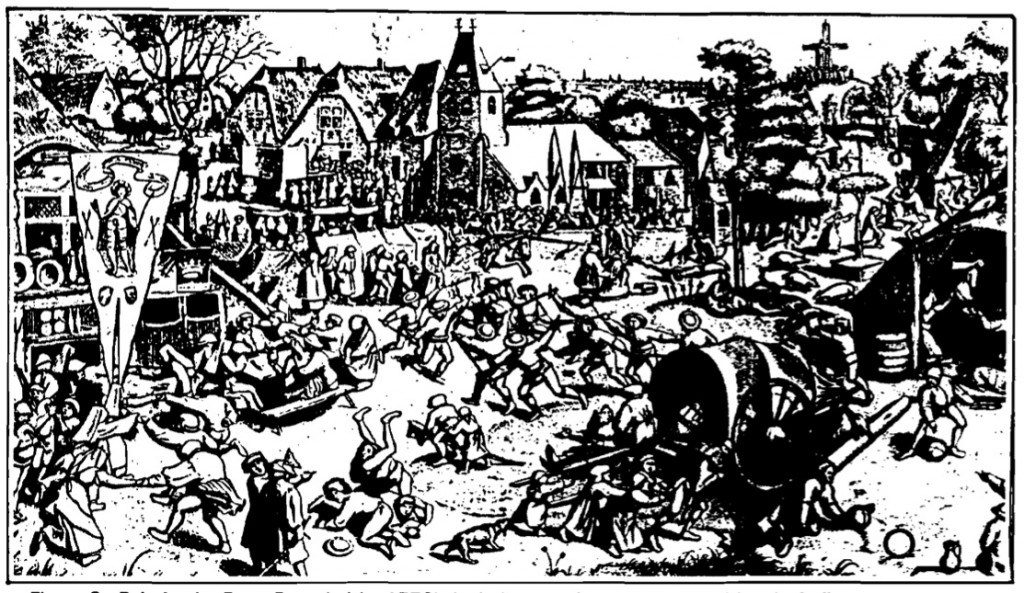

Abundant evidence exists for the use of bagpipes in ritual European dancing between about 1500 and 1800. To give some visual examples, I include a watercolor from the 1500’s showing a flautist and ‘dudelsackpfeifer’ leading St. Urban into the town of Nurenberg on May Day (Figure 2). Commentary accompanying the painting said that the procession was a formality used to herald in the May celebration. It also said that the ‘little’ people gamboling around with the dog probably drank too much in preparation! A version of the sword dance is seen in the center of Figure 3 which is a painting by Peter Brueghel (c.1570). This Flemish painting portrays the sword dance and other May revelry with music supplied by the two ‘doedelzakpfeifers’ in the lower left. In Figure 4 we see another German piper (c.1750) playing for two couples dancing around a Maypole. The last recorded images of these two-droned bagpipes in German popular art in the context of May Day festivals are dated 1804 and 1818. After that, the flute and drum are shown, especially with respect to the ‘Reifentanz’ (hoop-dance which is related to the ‘Fassertanz’ or Cooper’s dance), held at Fasching, or Shrove Tuesday (the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, in the Easter season). Amazingly similar to the German Reifentanz is the English Processional Morris, held at nearly the same time, in Lancashire, and known as The Garland Dance. Both the Gennan and English versions feature flower-decorated hoops held on high by the ‘disguised’ dancers.

Figure 2. St. Urban’s welcome to Nurenberg, from a watercolor dating to the middle of the 16th century. From Handbuch der Deutschen Volkskunde, Vol. II, by Wilhelm Dekler, 1939.

38

Figure 3. Painting by Peter Brueghel (c. 1570) depicting a variety of May activities, including a Low Country version of the sword dance (center), to the music of bagpipes (lower left). Same source as Figure 2.

Figure 4. A German bagpiper (c.1750) playing for a May dance (note Maypole with garlands). From Alte Musikinstruments, by Wilhelm Stauder, 1973.

39

Very little exists in the way of visual documentation of the Morris dance in England prior to about 1700. Add to this Cecil Sharp’s comments on the music played for Morris Dancing: “The pipe [a three-holed flageolet with a one octave plus three notes range] and tabor were at one time the traditional instruments of this country, and until recently they were almost invariably used to accompany the Morris dance.” He then refers us to Mersenne (1627) whose musical treatise included the pipe and tabor. But, Mersenne also spoke at length on bagpipes, which were clearly contemporary with the pipe and tabor (and flute and early oboe). We know that in Cecil Sharp’s day, which was a little over two centuries after the heyday of bagpipe playing in England, the fiddle and concertina were in use for the Morris (the Melodeon had not yet achieved widespread acceptance in England), and the pipe and tabor were already an historical curiosity.

So we turn to written sources, and here there is the issue of the word ‘pipe’. Our reference list becomes quite slim if we limit it to those passages spelling it out – b.a.g.p.i.p.e. Despite the difficulty, a pattern emerges, and we’ll start with a reference noted in the 16th century by Herrick (1516) of how the King [Henry VIII] and Queen went “a-Maying” at Shooter’s Hill and of the gorgeous decoration of the Maypoles, round which the lads and lasses tripped to the sound of the bagpipe:

“The Maypole is up: now give me the cup,

I’ll drink to the garland around it;

But first unto those whose hands did compose

The glory of flowers that crowned it.”

[G. Flood (1911) p. 83]

Then there is this account of the Morris Dance as related by Philip Stubbes in his Anatomie of Abuses (1583):

“Then march this heathen company towards the churchyard, their pipers pipying, their drummers thundering, their stumps daunsing, their bells jinglings their handkerchiefs fluttering about their heads, their hobbie horses and other monsters skarmyshing among the throng like madmen; and in this sort they go to the church (tho’ the minister be at prayer or preaching) dancing and swinging their handkerchiefs over their heades in the church like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise that no man can hear his voice…wherein they daunce all that day and all that night too. And thus these terrestrial furies spend the Sabbath-day. “

[C. Knightly (1986), p. 168]

We don’t know if he’s referring to bagpipes or whistles, but one is tempted to think by the description that bagpipes might contribute to the air of pandemonium. In a recently republished book called The Folklore of Herefordshire by Ella Mary Leather, S.R. Publishers Ltd. (originally 1912, republished 1970) there are excerpts from a pamphlet dated 1609 called “Old Meg…” which refers to bagpipes in a description of a Morris Dance held on the racecourse at Hereford. Notice in the title of the pamphlet that the Morris dance was considered (in 1609) to already be ancient, viz. “twelve hundred years old.” If we took that literally, we’d be back in the Romano-Celtic period of English history.

From: Old Meg of Herefordshire for a Maid Marian, Hereford Towne for a Morris Daunce, or Twelve Morris Dauncers of Herefordshire of Twelve Hundred Years Old :

“The courts of kings for stately measures;

The city for light heeles and nimble footing;

The country for shuffling dances

Western men for gambols

Middlesex men for tricks above grounde

Essex men for the hey

Lancashire for hornpipes

Worcestershire for bagpipes

but Herefordshire for a Morris dance puts down,

not only all Kent but very near

(if one had line enough to measure it)

three quarters of Christendom. “

40

“The musicians and the twelve dancers had long coats of the old fashion, high sleeves gathered at the elbows, and hanging sleeves behind, the stuff, red buffin, striped with white girdles, with white stockings, white and red roses to their shoes; the one six, a white jew’s cap with a jewel, and a long red feather; the other, a scariet jew’s cap, with a jewel and a white feather; so the hobby-horse, and so the Mayd-Marian was attired in colours; the whifflers [marshals] had long staves, white and red.”

Similar activities are noted for the Scottish Borders in the early 17th century, according to George S. Emerson (A Social History of Scottish Dance, McGill-Queens Press, 1972). He writes, “There were many violent changes in the way of life of the people during the reformation, but the love of dancing and sport and of the May Games was too strong for immediate elimination, especially when no suitable diversions were forthcoming as due recreation in a harsh life. Thus, in spite of all the laws, as late as 1625 six men were summoned before the Lanark Presbytery for ‘fetching hame a maypole and dancing about the same on Pasche Sunday.’ According to the Lanark Presbytery records, this dancing was done to the music of a bagpiper. The Lowland art of piping while singing and dancing is even implied in the following few lines from the 17th century poem, “Christs Kirk”:

“…. Tom Lutar was their minstrel meet, O Lord as he could lanss (leap),

He played so schill, and sang so seet, While Towsy took a transs;

Auld Lyghtfute there he did forfeit, And counterfeited France,

He used himself as a man discreet, And took up Morrice dance… “

In Yorkshire around 1610, according to Grattan Flood (1911), the “Morrice” was danced to the tune of an old song called “The Literary Dustman.” William Browne in his Britannia’s Pastorals (1625) has the following stanza from a May poem:

“I have seen the Lady of the May

Set in an arbour on a holy day

Built by the Maypole, where jocund swains

Dance the maidens to the Bagpipe’s strains.”

Other old tunes associated with the Morris dance are “Staines Morris” (William Ballet’s Lute Book, 1593), “The King’s Morisco” (Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, 1598), “Maid’s Morris” (Playford’s Dancing Master, 1651), “A Morisco” (Playford’s), “Fiddler’s Morris” (Playford’s), “Mock Hobby Horse” (Playford’s), and “Come, Lasses and Lads” also known as “The Rural Dance about the Maypole” (Westminster Drollery, 1672). A curious feature of “The Literary Dustman”, “Staines Morris”, “Maid’s Morris”, “Mock Hobby Horse”, and in fact many modern Morris tunes is that they fit very well on the bagpipe! Some people are inclined to believe that, especially regarding tunes of the 16th and 17th centuries, those that play well on the bagpipe may actually have been composed for that instrument in the first place. And this leads us into the last section of this article.

Playing Morris Tunes on Lowland Pipes

Of the two-hundred and sixty or so tunes listed in A Handbook of Morris Dances, by Lionel Bacon (1974), over three fourths of them can be performed with minor modification on the bagpipes. Often, only a few notes out of a measure need to be ‘bent’ around to make the tune fit neatly on the nine-note chanter scale. There are several obstacles to overcome, however, before jumping in and playing for dances. First, many of the tunes rely on a sharpened seventh note and leading note (the high g’ and low g on an ‘A’ chanter) for a true ‘major’ scale. Second, a solo Scottish smallpipe does not really produce enough volume to accompany a raucous team of Morris dancers. Third, the Morris dancers, as is the case with dancers in other folk traditions, rely on a ‘biofeedback’ loop of interaction with the musician. Special techniques must therefore be employed to bring out a rhythmic sense from the open chanter of the Lowland type of bagpipes. These same obstacles presented themselves to me when I began playing with the Welsh Tract Dancers, and I came up with some simple solutions which are described for a Morris dance tune below.

One of my favorite Morris tunes is Princess Royal, shown in full “G-scale” setting below (Figure 5). Since I am used to reading music based on a “C-scale” running from low g’ to high a”, I had to transpose the tune up one note, giving the setting shown in Figure 6. Playing through this setting on my Scottish smallpipe, there were some pronounced deficiencies, notably the low note situation in bar 6 of the first part and the occurrence of high g-sharp notes in the second part. To handle the low notes in bar 6 of the first part, I half-hole the low g’, which produces a nominal g’-sharp. Then, instead of playing low e (not available

41

on the chanter!) I play a regular e’ note (see Figure 7). I call this ‘bending the tune in half’ (with thanks to Sam Grier for the nomenclature). Another way of accomplishing this, without having to play false notes is to actually re-write the section as in Figure 8. In this version, I have also changed the high g’ notes, which were tolerable in the previous setting, but benefit from a little rearrangement.

Figure 5. Basic setting of Princess Royal (key of G major).

Figure 6. Princess Royal transposed up one whole note, to key of A major.

Figure 7. Princess Royal ‘bent’ slightly to fit bagpipe chanter. Notice that the low g’s are natural on the pipe chanter and must be false-fingered to give g-sharp

Figure 7. Princess Royal ‘bent’ slightly to fit bagpipe chanter. Notice that the low g’s are natural on the pipe chanter and must be false-fingered to give g-sharp

Figure 8. Final version of Princess Royal, ready for gracing and interpretation.

42

On the issue of volume, I have but two suggestions. If playing the Scottish smallpipes, then invest in an acoustical transducer (of the type sold for flutes and clarinets) and a portable amplifier. You’ll find that the transducer will not pick up the drones so well, but will produce a great rhythmic effect due to the constant fluttering of the hands against the walls of the chanter. The other suggestion is to use a Lowland or Border pipe, which has a far greater volume and carrying ability than a smallpipe.

Finally, the subtle issue of “how to make it sound good for dancing.” Here, it is a matter of experience and experimentation, relying on the feedback of the dancers. You might do well to listen to piping from central France, where the low chanter note (low A to us) is frequently referenced against the upper hand notes. Say you have a tune with three or four high a” notes in a row. Your first impulse might be to play doubling of the notes, rapidly wiping the thumb against its hole to articulate the notes. That is probably okay, but you might achieve a clearer articulation by shutting the chanter’ all the way down to Iow a’ between each high a”. The effect can be quite stunning and can even be used to cover ‘runs’ that just get lost in the mayhem. I find, playing for Welsh dancing, that getting a punctual rhythmic effect is far more critical than playing the established melody per say. When playing music based more on the low notes of the chanter, I find it useful rhythmically to use high g” and high a” gracenotes, in a ‘cutting’ fashion. I guess the rule ‘of thumb’ I abide by when playing for dancing is to stay away from movements which get lost in the shuffle and concentrate on single gracenotes which are tonally well-separated from the melodic structure.

So, to solve the problem of g versus g-sharp, learn to play the low-hand false notes, try bending the tune, or modify your chanter. If you find yourself playing a lot of tunes with g-sharp, you might consider having a pipemaker fabricate a chanter with the g-notes sharpened. I believe that this was the tuning system formerly employed on the Northumbrian half-long pipe. On such a chanter you could ‘tape’ the holes to flatten them if so desired. Better would be to have two chanters, though. So there it is, a bit of rambling about bagpipes and Morris dancing!

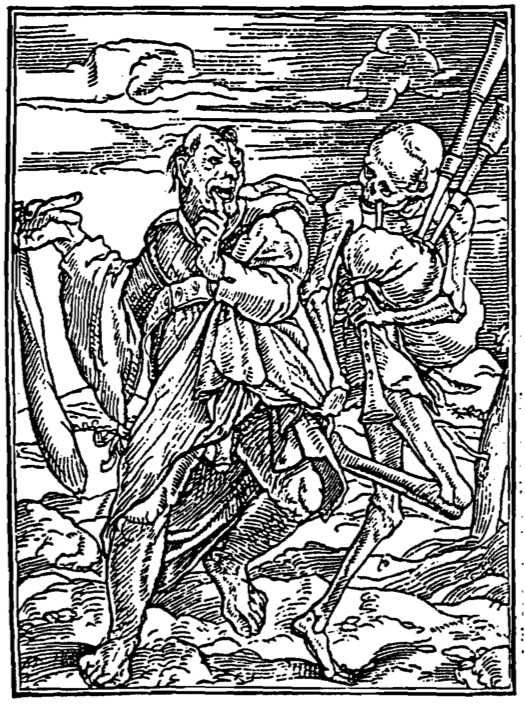

Woodcut by Hans Holbein from his Dance of Death published in 1538 in Lyons, France.

43

Making Yogurt Cup Smallpipe Chanter Reeds

From a workshop session with Mike MacHarg

15 March 1991

Materials needed:

- Brass tubing 3/16 outside diameter for staple. Each reed requires a piece 22mm long.

- 23 gauge copper wire. Each reed requires a piece approximately 11.5 cm(4 1/2″) long.

- An 8 oz yogurt cup (a 16 or 32 oz cup will do also).

- Thread to wrap the reed to the staple.

- Contact (rubber) cement.

Tools needed:

- Tube cutter (a fine tooth hobby saw can also be used but tube cutter provides better cut).

- Paper cutter or sharp scissors

- Oval mandrel to form end of brass tubing (can be done with needle nose pliers)

- Tool for holding staple during wrapping and sealing (the oval mandrel can be used for this task also)

- Tubing reamer or round file

- A straight bladed knife with burnished edge for scraping reeds (a utility knife or old paring knife will do).

1 – Blade tip

2 – Blades

3 – Bridle

4 – Wrapping

5 – Wrapping to fit to chanter

6 – Staple

7 -Scraped Area

_________________________________________________________

1. Mike McHarg, c/o Wee Piper, RFD #2, Route 14 Box 286, South Royalton, VT (USA) 05068

44

Instructions:

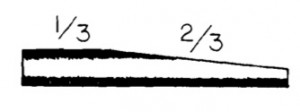

Cut a piece of 3/16 on brass tubing 22mm in length. Use the tube cutter or hobby

saw (latter is less precise) to cut the tubing. Ream or file inside ends to clean out burrs; use file to smooth ends and remove burrs from the outside. With a mandrel (or by eye with pliers) make approximately 1/3 of the staple oval shaped, gradually changing from round to oval.

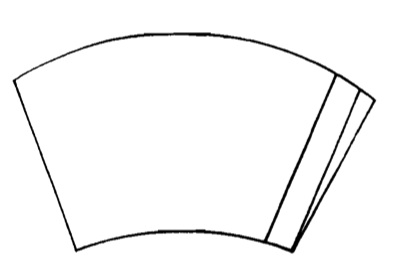

Cut a strip vertically from the yogurt cup. Use fine steel wool to remove printing from  plastic. Draw lines on the cup to make strips 13 mm wide for pipes in keys of C, Bb, or A; 11-12 mm for keys of D, E, F. (These are not necessarily gospel but they work. Experiment to find alternative widths if you choose.) Cut to lines. Because of taper of cup, after a few cuts the strips will tend to twist as they are not

plastic. Draw lines on the cup to make strips 13 mm wide for pipes in keys of C, Bb, or A; 11-12 mm for keys of D, E, F. (These are not necessarily gospel but they work. Experiment to find alternative widths if you choose.) Cut to lines. Because of taper of cup, after a few cuts the strips will tend to twist as they are not

cut vertically. Cut off a small triangle to get back as near vertical as possible. Trim

end square.

Cut the strip 29 mm long. Ensure that both ends are cut square.

Mark the plastic strip for shaping and wrapping. On the convex side of the plastic strip, draw lines across the strip at the 15 rom and 20 mm intervals; be sure lines are square to the sides of the strip. At the 20 rom line end, draw a line parallel to the sides. up the center of the strip. Use this median line to draw a diagonal from the 20 mmline at the edge of the strip to a spot approximately .75 mm from the center line. (See illustration).

Cut the shoulders of the reed.

Cut along the diagonal lines to form the shoulders of the

reed. The width of the center portion of the tail is not critical as long as both halves of the reed are the same.

45

Mark the staple insertion line. On the concave side of the reed half, mark a line

across the reed blades 10 mm from the tail. This indicates the depth of insertion of

the staple.

Cement blades to staple.

Apply a small amount of contact cement (a small

amount dries faster) to both the staple and the concave side of the blades up to

the 10 mm line. Lay the staple on the blade and adjust until the staple plus

blade is approximately 41.5 mm long (minimum 41 mm, maximum 42 mm). Set the other blade on top, line up the ends and sides and hold the blades to the staple until the cement sets. (Too much cement, or undried cement, makes the contact “slippery” and hard to hold in place.) Let cement set up thoroughly before tying the blades.

Tie blades to staple. Hold staple on tool and wind staple and blades with thread. Beginapproximately 8-10 mm up staple, wind once and overlap twice. Further wraps should be close together and not overlap. Wrap the first 8 – 10 turns tightly; then ease up on the pressure for additional wraps. “Wrap around the square – tighter on the comers and