By Barry Shears © 2010

Read on below, or download as a pdf to read.

One of the essential tune genres in Cape Breton dancing today is the Jig. The tradition of performing rural dances to jigs was brought to Nova Scotia by the early settlers who left Scotland between the years 1773-1850. By the end of the 19th century there was a noticeable expansion in jig playing and composition among dance musicians in the region. One of the major reasons for this transformation was the introduction of foreign influenced dance styles which were eventually grafted onto the existing tradition. These influences had a lasting impact on the evolution of social dance in rural North Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton.

Historically speaking the Maritime Provinces of Canada have at various periods been economically disadvantaged, and this problem was compounded after the region joined Canada during the second half of the 19th century. A shortage of employment opportunity at home led many Maritimers “Down the Road” in search of work. Beginning in the 1880s the United States proved to be an attractive destination for sailors, tradesmen and domestics from the Maritimes. For many in Eastern Canada, the area south of and including the state of Maine was often referred to as the “Boston States” and a large number of Nova Scotians, many of which were from North Eastern NS and Cape Breton, found work in the Boston area.

The modern square set danced in Cape Breton and parts of Nova Scotia today is derived from the Saratoga Lancers and the Quadrilles. These two essentially European dances were introduced to Nova Scotia by people who had permanently returned from the United States or were home visiting relatives (often to help “put in the hay”). The Lancers and Quadrilles proved quite popular and eventually displaced traditional social dances such as the Scotch Fours. These imported dances, which required numerous jigs and later reels to perform, were widely adopted, transformed, and Gaelic-ized to incorporate traditional step dancing technique and evolved into a unique form of social dancing.

In Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, the piper provided much of the dance music for social dancing in the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. The tradition of dance piping in Prince Edward Island has yet to be studied in detail, but in Nova Scotia, quite often the piper was also a fiddler and these community musicians drew on a common store of tunes.

There are several fine examples of jigs common to both the Scottish and New World tradition and these include such tunes as The Tailor’s Wedding, The Drover Lads, The Hills of Glenorchy, The Lads with the Kilts, and The Stool of Repentance. While these tunes are immediately recognizable from their melodic structure there are still many variants of these tunes which exist in both North America and Scotland. The increased popularity of the square sets among younger people in the region eventually created a need for new material, especially jigs, in the repertory of dance musicians. Pipers and fiddlers adopted standard 6/8 pipe marches such as Atholl Highlanders, Piobroch of Donald Dhu, Cock of the North, Glendaruel Highlanders,The Bonawe Highlanders as well as many others into their repertory. Many good 6/8 pipe marches, particularly those with a strong melodic line, make excellent jigs by merely playing them a bit rounder and faster.

The performance of the jig in North America has transcended cultural diversity and can be found in many folk traditions from the French influenced Quebecois/ Acadian/ Metis fiddling styles, Irish -flavoured Ottawa Valley style, and the Scotch-Irish old time fiddling traditions in many parts of the United States. For players of the GHB, SSP and Border pipes, jigs are fun to play and versatile when played in sessions or for dancers.

Early History

The origin of the dance form known as jig has been attributed to many European countries including Italy, England, and Ireland. In Scotland it achieved a certain amount of popularity in the 17th century under the Stewart monarchs. A “Scotch Jig” is mentioned in Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing (1599) and there are several examples of jigs in John Playford’s Dancing Master (1651) which was reprinted and updated many times until the mid 18th century.

In Scotland one only has to look at the printed record to see just how common jigs were among pipers. The earliest collections of music compiled by pipers such as William Gunn, David Glen, Angus MacKay and William Ross contain numerous jigs. However, by the early 20th century music collections such as Betts, MacKinnon, and Logan show the increased prominence of competition style marches, strathspeys and reels and fewer jigs. The decrease in published jigs in the early 20th century may be attributed to the continued availability of many of the collections by David Glen and others during this period which continued to provide a wider variety of melodies.

By the mid 20th century the written record shows an explosion of jig composition and the inclusion of four-parted arrangements of what had traditionally been two-parted Irish and Scottish jigs. Dozens of new compositions and arrangements by Donald MacLeod, Duncan Johnston, John MacLellan, Peter MacLeod and John Wilson, as well as many others, began to appear in print and by the 1960-70s competitions for jig playing had been introduced at many Highland Games, both on mainland Scotland and North America.

Expression, Phrasing and Tempo

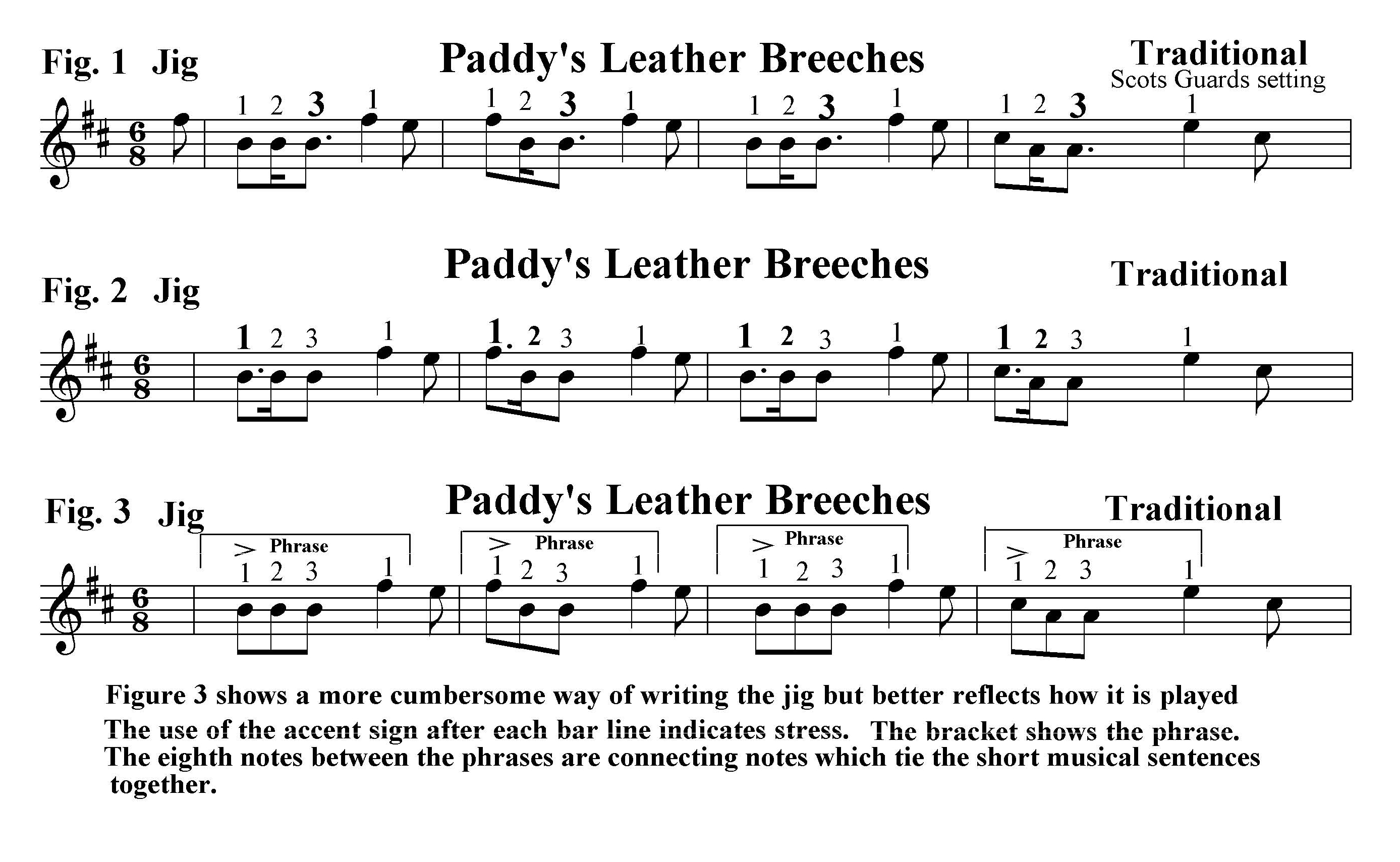

As a young piper growing up in Nova Scotia, and entering into competitive piping in the 1970s, I spent a lot of practice time learning jigs, partly for the mechanics and sheer delight in playing and also for the chance to show off what I thought at the time was versatile fingering technique to some of the older pipers in the local pipe band. During the 1970s and 80s there wasn’t much consensus in the piping world as to the proper expression of a competition jig. Scottish pipers I had heard on recordings, etc, played their jigs very pointed with most of the emphasis on the last of the three note combination (Figure 1). From my perspective this always seemed to be a foreign way of playing this particular genre of dance music on the bagpipe. In the 1970s there seemed to be no consensus regarding the expression of jigs. I attended a few piping workshops during this time and some prominent pipers wanted the jigs played round, others wanted them played pointed (Figure 2), and to confound matters even more, one judge wanted jigs played neither round or pointed but “shaded”. Since the bagpipe lacks the dynamics of other instruments – dynamics being the ability to play a note louder or softer- the ‘shaded’ (or what I now call a sing-song or lyrical) method of expression seems to be the most effective (Figure 3). Play it like you would sing it.

The continuity of sound produced by a set of Scottish bagpipes, regardless of the type (SSP, BP or GHB), also presents difficulties in phrasing. A singer may take a breath to accentuate a phrase; a pianist might pause and rest between musical passages or play more loudly to accentuate a phrase, not so the piper. Our music is continuous, or it is supposed to be. To give the illusion of pauses in the music, the piper must pay particular attention to the phrases and sub-phrases inherent in our music, and jigs are no exception. In the case of jigs written in 6/8 time, pipers must be conscious of the Metric Accent. 6/8 jigs are in Compound Time and have a Metric Accent on the beat notes of each bar of Strong/Weak. Jigs require a certain lilt when played and this is achieved by the subtle holding and cutting of notes, with particular emphasis on the beat notes after each bar line.

Jig tempi vary from tradition to tradition but in Cape Breton jigs are usually played between 120- 128 beats per minute (BPM) for dances. Musicians often knit together several melodies into sets and usually two parted jigs are played twice through and four-parted tunes played once through. When sitting down, it is much easier to beat out the rhythm of the jig with one or both feet. The heel of one foot beats out the strong and weak pulses while the toe of the same foot (or the other foot if preferred) beats out the off beat. The stress, of course, falls on the heel beat with a slight pause before the off beat. This gives you a / ONE –two –three ONE -two –three / (1-2-3 1-2-3 or Jiggidy Jiggidy) rhythm per bar.

There are quite a few jigs written for the violin which, with a little adaptation, can be played on the SSP, BP or GHB. The availability of keyed chanters, such as a High-B key on an A Scottish Small Pipe chanter, makes this transition much easier. Without a High-B key, the piper must compress the melody slightly and may have to make minor changes to the melody to get it to fit on the chanter.

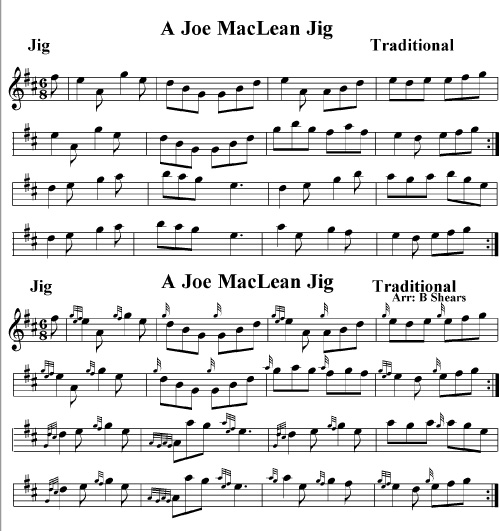

Featured below are two arrangements of the same tune. The first is written as played by some fiddlers in Cape Breton, and the second is my arrangement of the same tune for non-keyed bagpipes. I picked up the tune from a tape recording of the late fiddler, Joe MacLean. MacLean was a great player and composer who is still highly regarded in Cape Breton music circles. I have checked several collections of fiddle tunes for this tune without success. It may have been composed by him, or picked up from one of the many other fiddlers in Cape Breton, or borrowed from another tradition completely. (If anyone finds the tune please, let us know and we can add a title and source.)

For more information about Barry Shears and his music, please see his great website.