By Barry W. Shears

Many of the early Highland immigrants to the Maritimes were pipers, and in addition to bringing Scottish-made bagpipes to Nova Scotia, they and their descendants constructed bagpipes using local materials [1]. Bagpipes were an integral part of the musical culture of the immigrant Gael and omnipresent among the Scottish Gaels who settled North America. Dr. Abraham Gesner, the noted scientist and inventor, commented in 1843 that “In a Highland settlement a set of bagpipes and a player should not be forgotten. I have known many a low-spirited emigrant to be aroused from his torpor by the sound of his national music”[2]. The number of instruments available in these communities was disproportionate to the numbers of people who could actually play them, and in some areas of Nova Scotia one set of bagpipes would serve several family members. The early settlers and their descendants held the national instrument of Scotland in very high esteem. Many people could play a few tunes on homemade chanters but very few could afford to purchase a new set from Scotland. As the numbers of pipers in the province increased, a growing market for inexpensive, locally produced instruments emerged.

Continuing research has identified numerous individuals in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick who have made at least one set of pipes in the late 19th and early 20th century. My personal collection of pipes now contain an almost complete set of Duncan Gillis drones, but chanters made by him are extremely scarce. Duncan never stamped his pipes but his unique design, like a fingerprint, make them easily identifiable.

The most notable features of the surviving examples of locally produced instruments which have recently come to light, are the number and size of the drones. Duncan Gillis, Grand Mira, made only two-droned sets at first, adding a bass drone when requested to do so. Two droned sets (2 tenors) were ideal instruments on which to learn to play since they were less cumbersome without the bass drone especially for children. Two-droned sets of pipes were banned from competition by event organizers in Scotland after 1821 due to a perceived disadvantage on the part of several competitors. In recent years recently discovered examples of two-droned bagpipes have surfaced. Many of the bagpipe-makers in Nova Scotia would undoubtedly copy the sets originally brought from Scotland. This might explain why surviving examples of Nova Scotia bagpipes are noticeably smaller and more delicate in appearance than their modern Scottish counterparts. These local examples illustrate a wide variety of designs which support Hugh Cheape’s opinion that the modern bagpipe as we know it is a fairly modern configuration dating from the late 18th – early 19th century [3].

Since the Highland immigrants had very little money to purchase things such as reeds for the instrument, several pipers became quite proficient at making reeds from a variety of local materials. The MacIntyre pipers of French Road, Cape Breton County and later Glace Bay, made chanter reeds from old cane fishing rods [4]. Other pipers used small pieces of birch bark or maple tied to a copper or brass tube or staple. In some instances a family member made the reeds for pipers within their own extended family. This was the case with “Little Hell” MaKinnon, (another nickname) Meat Cove and Angus MacMillan, Glen Morrison, Cape Breton.

Sheepskin was normally used for the pipe bag since cowhide was too stiff. A single piece of hide would be folded over and stitched using a heavy needle (sometimes a porcupine quill) and waxed thread and affixed to the drone stocks [5]. John Jamieson of Piper’s Glen, later Glace Bay, used two barrel staves with screws attached to make a vice in which to hold the bag in place while being stitched. To make the bag airtight, a variety of mixtures were used to dress or season the pipe bag. These included the whites of two eggs and a little sugar which produced an odorless rudimentary adhesive, or either molasses or honey. Drone reeds were crafted from elder, known as drumanach in Gaelic [6]. Practice chanters, a small flute-like instrument used to initially learn the instrument and practice new tunes, were made from young maple trees. Once a small maple tree was selected and cut, it was left to dry for a few days and then the soft centre core or heart was burned out with a long wire rod heated in the fire. The positions of the finger holes were marked and then burned out in similar fashion [7]. Practice chanter reeds were usually made from a piece of oat straw flattened at one end.

One of the most successful pipe makers in Nova Scotia was Duncan Gillis, Grand Mira, Cape Breton County.

Usually referred to as Duncan ‘Tailor’. He was born at Upper Margaree, Inverness County around the middle of the nineteenth century, but later moved to Grand Mira, Cape Breton County to be closer to relatives. His occupation is listed as ‘Turner’ in Lovell’s Nova Scotia Directory of 1871 and, in addition to making spinning wheels, he made a profitable sideline of making and selling bagpipes around the province. Duncan Gillis made bagpipes from apple wood and mounted the instruments with bone, cattle horn and brass.

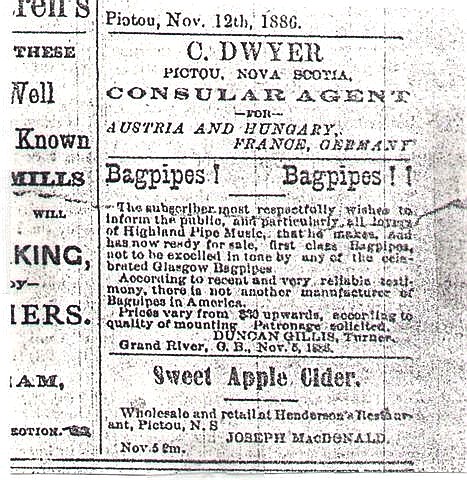

An advertisement soliciting patronage, but with what appears to be a variation on Grand Mira, appears in an 1886 issue of the Pictou News where he claims to be “the only manufacturer of bagpipes in North America”. Duncan Gillis lived at Lewis Bay on the Mira River and not Grand River, which is in neighbouring Richmond County.

Gillis was so successful at making bagpipes that he was the subject of a Gaelic song, Song to Duncan Gillis of Mira, Maker of Bagpipes (Òran do Dhonnchadh MacGill-iosa, am Mira, Fear a Tha Deanamh Phioban Ciuil) composed by the Margaree Bard, Malcolm H. Gillis, in praise of his musical craftsmanship and upstanding character. Malcolm Gillis was a renowned bard and musician from South West Margaree. He could play the bagpipes, violin, piano, organ, Irish pipes, and whistle, and several of his songs were published to wide acclaim in Scotland [8] The poem alludes to a long-standing tradition of piping in Duncan Gillis’ family and perhaps one of his ancestors also made bagpipes [9].

Thainig sgeul oirnn o chionn bliadhna,

Sgeul a riaraich mi neo-throm,

Sgeul bha taitneach leis gach Gàidheal

A chaidh àrach anns an fhonns’:

Donnchadh Tàillear bho an Bhràighe,

Fear mo gràidh as aille com,

A bhith deanamh phiob am Mira:

Beannachd air a laimh nach lom!

We received news a year ago

News which pleased and cheered me

News delightful to every Gael;

Who was brought up in this area:

Duncan Tailor of Upper Margaree

My dear handsome man

Is now making pipes in Mira-

Blessings on his bountiful hand!

Beannachd air a làmh neo-chearbaich

A tha ainmeil air gach gniomh,

’S air an eanchainn anns ‘n do chinnich

Móran grinnis ‘s am bi sgiamh!

’N a chuid obair cha bhi fàllinn,

Ach gu dealbhach, làidir, dion-

’S beag an t-ioghnadh ’s gu ’n robh chàirdean

Eolach, talantach o chian.

Blessings on his skilful hand

Noted for every task,

And on his intellect which produced

Much artistic beauty:

There will be no defect in his work

It will be shapely, firm and secure,

Small wonder as his people were

Adept and talented long ago

Duncan Gillis continued to make bagpipes until just after the First World War and in recent times samples of his musical instruments have turned up in such diverse places as Ontario and Glasgow, Scotland [10]. Another pipe-maker from Grand Mira was ‘Old’ Allan Gillis, who also made a few sets of bagpipes in the late nineteenth century. Allan ‘Turner”, as he was known, was employed as a wood turner at a shipyard at Fourchu, Richmond County, and this job gave him access to tropical woods like lignum vitae, a very oily wood used in the manufacture of various items necessary on sailing ships such as pulleys, blocks and dead-eyes [11]]. A blood relationship between these two pipe-makers has yet to be established but, since they were from the same area, it is possible that Duncan apprenticed his trade with ‘Old’ Allan Gillis.

Another member of the Gillis family of Grand Mira, Joseph (nicknamed “Creamery Joe” to distinguish him from other Joe Gillis in the area) also made bagpipes, although how many sets is currently unknown. He was an inventor as well and could turn his hand to almost any task.

Bagpipe making in the Canadian Maritimes was never a large-scale operation and except for Duncan Gillis it usually consisted of a handful of artisans making a few instruments for community or family members throughout the region. More disposable income in the region after industrialization in the late 19th century and a desire for Scottish made bagpipes in the 20th century signalled the end for this small cottage industry. For hobbyists and historians these artistic and utilitarian relics of the past are an interesting narrative to the piping tradition in North America.

FOOTNOTES

1 – Appendix C. in Shears, Barry W. 2008. Dance to the Piper; The Highland Bagpipe in Nova Scotia. Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, Nova Scotia.

2 – Appendix, p. viii. in MacDonald, R.C. 1843. Sketches of Highlanders. St John, N.B.

3- Cheape, Hugh. 2008 Bagpipes. A National Collection of a National Instrument. National Museums of Scotland. Edinburgh.

4 – MacDonald, Jim. 1968. Piping in Cape Breton. Piping Times 21(2): 9.

5 – Personal Interview, Alex Matheson.

6 – Ibid.

7 – Personal Interview, Alex Currie.

8 – MacGillivray,Allistir.1981. The Cape Breton Fiddler. College of Cape Breton Press. Sydney, Nova Scotia

9 – This song was published in Hector MacDougall’s The Songster of the Hills and Glens in 1939, a translation of which was kindly sent to me by Effie Rankin, Mabou, NS. A complete version of the song in English can be found in Appendix D in Dance to the Piper: The Highland Bagpipe in Nova Scotia (see note 1).

10 – Jim MacDonald also refers to a set of Duncan Gillis bagpipes on display in a museum in Sydney, Australia in MacDonald’s ‘Piping in Cape Breton’ (see note 3)

11 – Personal Interview, Arthur Severence, Fourchu, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Barry Shears is a Cape Breton piper currently residing in British Columbia, a researcher and the author of three tune-books arranged for pipers. His specialty is traditional dance music played in the Gaelic style. He is also author of Dance to the Piper; The Highland Bagpipe in Nova Scotia. Barry is a founding member of Alternative Pipers of North America.