By John Dally

There are new ways to get your music heard and hear other musicians, who often equal or surpass those with credentials, contracts and crowd funding. The best one I know of is SoundCloud. I now rely on it for the kind of “alt piping” I love to listen to. This is the best example of “community” I’ve found on the web, which for the most part is a mercantile place made for bullies. As the business – and I use the term lightly – of traditional piping changes and becomes more difficult every day, it’s good to look at where we have been and where we can go.

Back in the ‘70’s when I was a young person fascinated by what the music business calls Celtic Music, I bought vinyl recordings of masters like Seamus Ennis and John Doherty, as well as the young musicians who made up the Folk Revival, like the Boys of the Lough, Finbar Fury, and Paddy Keenan. Anything on the Topic label could be counted on to be worth the price, like the BORDER MINSTREL recording of Billy Pigg. That record was my introduction to the Northumbrian small pipes. This was all long before the resurgence of or invention of the Scottish small pipe.

The record bins of even the largest stores in Seattle at that time had very few items to select from, and there were very few people playing the kind of music I was interested in. The only Highland piping albums available there were of military pipes and drums, usually with military band accompaniment. So I spent my hard earned money on whatever I could find that wasn’t obviously commercial. Shamrocks and faeries on the cover were a dead reckoning I’d be disappointed with what was inside.

The idea of recording anything myself was an impossibility to imagine, even if I ever did get good enough. The cost was prohibitive. Distribution was a mystery. And then there was the question of whether anyone would buy it. There were very fine, local traditional musicians, like Dale Russ, Mike Saunders and Mark Graham, who did record. They were an inspiration, became good friends and remain so to this day. None of them are rich.

When cassette tapes and then CD transformed the market folk musicians could more easily make a recording and sell it, either by subscription, consignment or in person. It was never extremely profitable, but it could pay for itself over time. For an outlay of five to ten thousand dollars you could record, produce, master and package one or two thousand units. It might take five to ten years to make your money back, but it got your music “out there.” If you were very fortunate one of your tracks might get played on the radio, or on NPR as filler, or better yet used in a movie sound track. It might send some money home. But recording a CD became a necessity for the serious folk musician. Without it no one took you seriously.

Today opportunities for folk musicians to make a living or supplement one are fewer than they have ever been in my memory. Yet the paradigm remains of going into a studio, producing, mastering and packaging a product to be sold. But music stores don’t exist any longer. The makers of digital music devices have taken their place. Mp3 changed distribution beyond recognition. While we love the convenience of these gadgets they facilitated a huge transfer of wealth from the music business and musicians to the companies that make the devices. The public “rip” music without paying for it guilt free. The idea of creating a piece of work, housing it in a permanent medium, and providing interesting liner notes, is nearly unknown to the market today. There is resurgence of interest in vinyl, however, because of its warm sound and large graphic canvas.

While schools, like the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, train musicians for the marketplace there are fewer opportunities than at any time that I can remember. The normal gig pays a fraction in real dollars of what it did forty years ago. These young hopefuls perform and teach to make a living. I don’t know how they do it without some other source of income (a trust fund, a spouse, a “real job”). They are still wedded to the old paradigm. They use crowd funding and grants to raise the money to go into the studio, hire an engineer, a producer and to get the recording mastered and packaged.

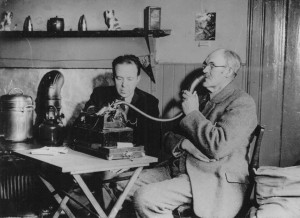

This is a far cry from Calum MacLean recording Calum Johnstone in Barra on his ediphone, an early portable recording device.

There is hope. Home recordings have never been easier to make using some of the same devices that brought down the music “industry.” We have many times the self recording ability of previous generations in the devices we carry with us every day: mobile phones, tablets and laptops. Programs such as GarageBand and the soundcloud app make recording and posting to the web easier than making a cup of tea, a proper cup of tea.The quality is not as good as a recording made in a professional studio, but neither is any mp3. The quality is worlds better than those made by Calum MacLean, however. And they serve the same purpose, to record a moment in music, which is what traditional folk music is no matter how people try to profit from it. For very little money or none at all, you can make your recordings available for others to listen to on SoundCloud. The intent is not the same as making an album pressed in vinyl and getting a distribution deal, making a living at playing music, or seeing your name up in lights. It does get your music “out there,” which is the important thing.

This gift economy creates a better sense of community than Face Book or other forms of social media, at least in my experience. It will never replace real community, an actual session, the magic moment of a chance meeting with another musician in a pub. When Seamus Ennis drove the back roads of Galway in search of musicians and singers he never knew what he would find in the next village. But surfing SoundCloud is fun and informing.

These links to my Northumberland piping friends will provide, I hope, a trail head for your adventures.

https://soundcloud.com/wallie-ogilvie

https://soundcloud.com/bill-wakefield

https://soundcloud.com/edric-ellis

https://soundcloud.com/chrisormston

https://soundcloud.com/northumberlandsmallpiper

John Dally of Burton, Washington has been playing bagpipes since the age of 11. Equally comfortable with Highland, Lowland and Northumbrian pipes and repertoire, John is the author of “The Northwest Collection of Music for the Scottish Highland Bagpipe. A Collection of Music, Photographs and Essays,” and is a founding member of Alternative Pipers of North America.